John Anderson Collins (birth and death dates unknown) may be the most picaresque, if not knavish, character to leave his mark along the Freethought Trail. The record says that he hailed from Massachusetts, a onetime orthodox clergyman who had lost his faith and become fascinated with socialist literature. The Utopianism of François Marie Charles Fourier especially fascinated Collins, which is not to say that he understood Fourier clearly. (Among other things, Collins viewed Fourierism as an atheistic doctrine, whereas Fourier was strongly if quite eccentrically Christian.)

Collins first appeared in west-central New York State in the spring of 1843, convening meetings in Syracuse and Skaneateles with the aim of establishing a putatively Fourierist Utopian intentional community in the latter city. Throughout this period, he was a paid agent of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, whose faraway directors thought he was devoting himself to abolition work.

In May 1843, the Utopian Skaneateles Community was founded as a joint-stock association. Among locals who embraced the project was physician and reformer Hezekiah Joslyn, who joined a small committee to vet applicants to join the Community.

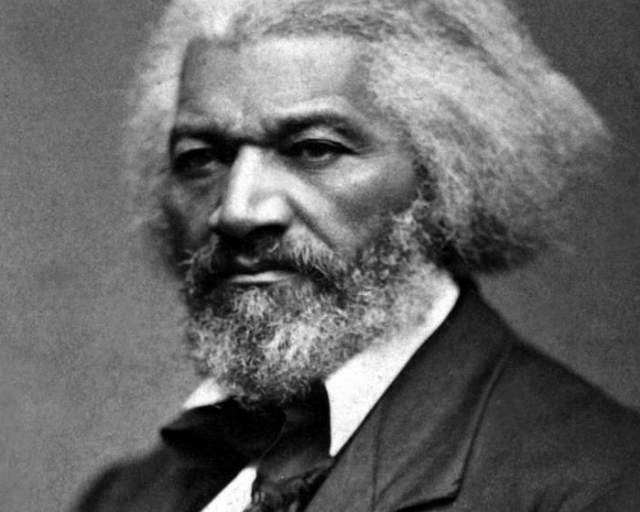

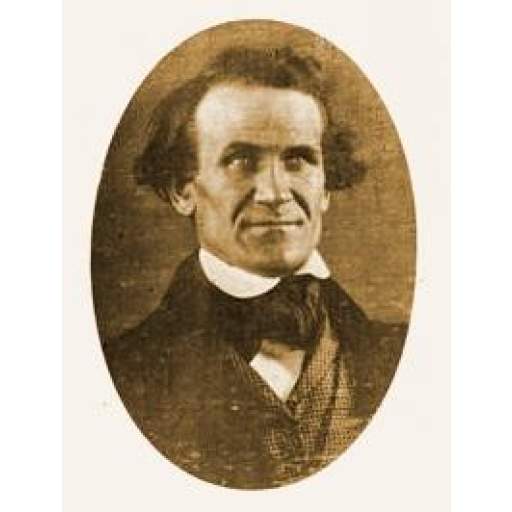

In July 1843, Collins had to resume anti-slavery work when he was assigned to assist Frederick Douglass during a recruiting stop at Syracuse. Abolition was still a widely unpopular cause, and Collins had failed to secure a hall where Douglass could speak. Instead, on July 30, the great orator delivered a historic lecture at Fayette Park, now Firefighters’ Memorial Park in downtown Syracuse. To Douglass’s intense annoyance, Collins’s own remarks said little about ending slavery but instead promoted his communalist project. Much time was devoted to a scheme to abolish private property, whose debt to Fourier’s theories was unclear. Douglass angrily complained to the Anti-Slavery Society’s headquarters in Boston, threatening to resign if he had to work again with someone who viewed abolition work as "a mere stepping stone to his own private theory of the right of property holdings." Collins was dismissed.

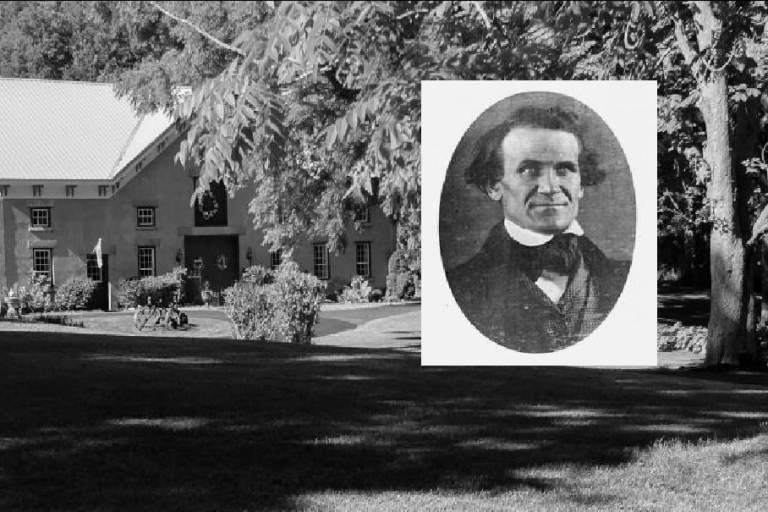

For better or worse, Collins was thus freed to devote himself to the Skaneateles Community full-time. In August 1843, he paid $15,000 (a sum he had raised from others) to purchase a 300-acre farm with buildings in the hamlet of Mottville, outside Skaneateles. On October 14, the community was formally launched with a convention held in the property’s barn. Speakers included Collins and the atheist firebrand Ernestine L. Rose. Attendees included Hezekiah Joslyn, his wife, Helen, and their teenage daughter Matilda, in future the suffrage activist Matilda Joslyn Gage.

On November 19, 1843, Collins published a set of "articles of disbelief," formally committing the Community to a radical program of atheism, free love, rejection of government authority, the renunciation of private property, vegetarianism, and the like. This was too much for the Joslyns and four other original Community members, who promptly withdrew. Collins backtracked and issued a more moderate statement that said, in part, "... We repudiate all creeds, sects, and parties.... We estimate a man by his acts rather than by his particular belief." The Joslyn family and the others who had withdrawn did not return; more followed suit.

Formal Community operations began in January 1844. Of the many ostensibly Fourierist communes that sprung up in the 1840s, the Skaneateles Community was the only one founded on secularist principles and with a population made up mostly of freethinkers. By January 1844, the Community and its grounds were in fine order, but there were only ninety residents, not the 150 originally projected. The Community was economically nonviable, a fact that grew more obvious with the passage of time. in April 1846, a Skaneateles newspaper unfriendly toward the community editorialized that "...the bonds of infidelity are not suited to hold men together in social harmony."

In May 1846, Collins called a meeting, declared the Skaneateles Community a failure, resigned as its leader, and promptly vanished. That August, a traveler discovered him in Dayton, Ohio, where he was publishing a Whig newspaper. In 1850, from an unknown location, he completed the sale of the Mottville farm to a former member of the Community. In 1853 he surfaced again in California, where he ran unsuccessfully for governor of that state as an Independent. He would pop up twice more: in 1865, a Syracuse man spotted Collins while visiting California; he was then a land promoter. And in December 1885, he appeared in New York City as a lecturer on geology, a subject on which he was not previously known to be expert.

The place and circumstances of Collins’s death are unknown.

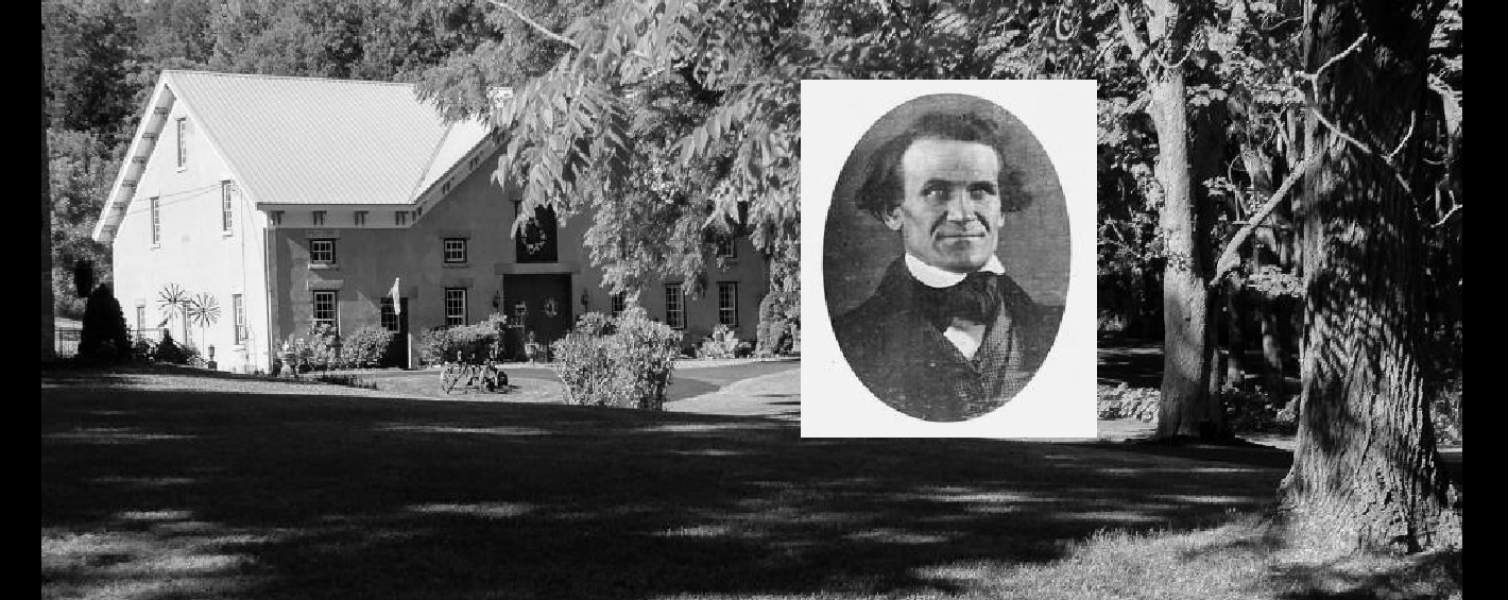

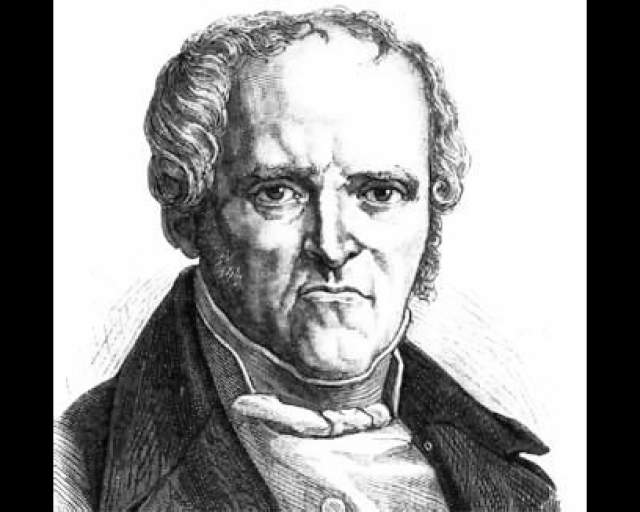

John Anderson Collins

John Anderson Collins.

Associated Historical Events

Frederick Douglass Outdoor Lecture Series at Syracuse

July 30–August 2, 1843

Meeting of Fourier Society of Rochester

November 21, 1843

Rise and Fall of Skaneateles Community

1843–1846