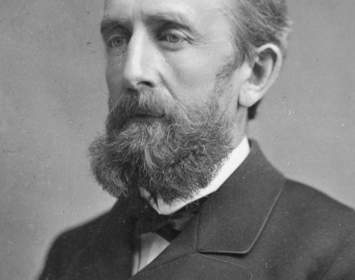

Geneva’s Hobart and William Smith Colleges, collectively The Colleges of the Seneca, form a much-respected institution today. Yet one of its constituents, Hobart College, has an ironic element in its past. The founding president of Cornell University was at least partly inspired to cofound Cornell, the Finger Lakes’ sole Ivy League academy, because he had been so deeply disappointed by his student days at a precursor of Hobart College.

In 1849, the 17-year-old Andrew Dickson White enrolled in Geneva College (chartered 1825), a small Episcopalian institution chosen by his wealthy father. (Geneva College became Hobart Free College in 1852 and Hobart College, its present name, in 1860.) Young Andrew, a bookish lad with perhaps an unrealistically romantic view of higher education, found the experience dreadful.

"The college was at its lowest ebb," White later wrote in his 1905 autobiography; "of discipline there was none; there were about forty students, the majority of them, sons of wealthy churchmen, showing no inclination to work and much tendency to dissipation." For example, White recounted, "One favorite occupation was rolling cannon-balls along the corridors at midnight, with frightful din and much damage." White concluded, "I have had to do since, as student, professor, or lecturer, with some half-dozen large universities at home and abroad, and in all of these together have not seen so much carousing and wild dissipation as I then saw in this little 'church college' of which the especial boast was that, owing to the small number of its students, it was 'able to exercise a direct Christian influence upon every young man committed to its care.'

Whether Geneva College was truly as bad as all that is a matter of conjecture. It may be worth noting that when Andrew prevailed upon his father to let him enroll at Yale instead, the youthful scholar found that experience disappointing also.

In any case, the demanding young student was finally satisfied by his graduate study at the University of Berlin in Germany. Given the opportunity to help found Cornell in 1865, he was motivated by a desire to replicate the academic experience he had known in Berlin—the polar opposite of what he had known in Geneva in 1849.

HWS Sign

One of several signs marking entrances to Hobart and William Smith Colleges today.