Utopian Sites

Custom

63.0 Miles

This trail extends from Sodus Bay (north of Rochester) on the west to Syracuse on the east. All sites on this list include a historical marker or a historic structure.

Call it the “pet rock” craze of the 1840s. Thousands of Americans flocked to form some 300 ill-fated utopian communes. Two, both in west-central New York State, operated on freethought principles.

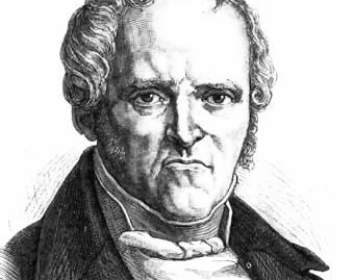

One of the oddest phenomena ever to sweep America was Fourierist Utopianism. In the wake of social shocks including the financial Panic of 1837, reformers across the youthful nation were smitten by the peculiar theories of the French thinker Frances Marie Charles Fourier (1772–1837). In an 1821 book, Fourier had proposed communities organized into “phalanxes” freed from private ownership in order to provide economic comfort, social justice, and individual fulfillment while resolving the differences among capital, management, and labor. (Phalanx, the English term for a Fourierist community, echoed the French phalanstère, a coinage by Fourier combining the French words phalange [phalanx, a basic ancient Greek military formation] and monastère [monastery].)

Fourier’s theory of “attractive labor” held that all work could be achieved free of the evils of capital and private property when individuals came together, each following his or her natural proclivities. None of this was based on any concrete life experience; it simply sprang from Fourier’s brain—as did his conviction that phalanx life should include free love, which nonetheless led him to an early defense of woman’s rights (nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's). Fourier also proposed a complex mystical cosmology and jarringly predicted that when the perfect society was achieved, the seas would (literally) lose their salt and turn to lemonade!

Even so, Fourier’s thinking struck a surprising chord among social radicals. The 1840s saw no fewer than three hundred attempts to build Fourierist "intentional communities" across America. Few such communities followed Fourier’s principles closely; even fewer interpreted them in the same way. But most involved some level of communalism, whether in the form of shared labor or something more radical, such as sexual access to one another’s spouses. Most survived for a maximum of three years.

Only two Fourierist intentional communities were wholly or significantly based on freethought principles: the Skaneateles Community and the Sodus Bay Phalanx. Both were founded in west-central New York State late in 1843 and failed by 1846.

By fall 1846, no Fourierist community, religious or otherwise, survived between Rochester and Syracuse.

Many intentional communities of the 1840s featured economic, social, or sexual practices that former members—and, later, their descendants—would find shameful. For that reason, the history of the Fourierist craze is often difficult to uncover because records were deliberately destroyed by family members and sympathetic archivists.