In the years before the Civil War, many Northern churches split over the issue of how radically slavery should be opposed. In 1843, relatively liberal Methodist churches split over whether to oppose slavery abstractly (a sort of bare-bones abolitionism) or to engage in more radical forms of activism such as defying the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, sheltering escaped slaves, and participating in the Underground Railroad.

Radical-abolitionist Wesleyan Methodist churches became associated with other radical reform causes including woman’s rights. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's). The woman’s rights conference that launched the nineteenth-century suffrage movement was held at a Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls in 1848.

The Wesleyan Methodist Church in Penn Yan split from a more mainstream Methodist congregation in the early 1850s. On January 10, 1855, it was the site of a woman’s rights convention modeled on the Seneca Falls convention seven years earlier. The principal speakers included Susan B. Anthony, a principal leader of the suffrage movement, as well as New York-based freethought and feminist orator Ernestine L. Rose, an outspoken advocate not only of feminism but also of atheism and freethought.

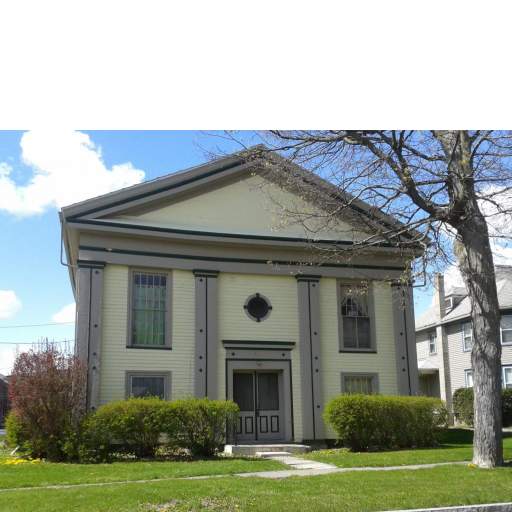

As the Civil War neared its conclusion, the breach between moderate and radical antislavery churches healed. In Penn Yan, the radical Methodist congregation rejoined its parent body; the wood-framed Wesleyan church was retired and became a private residence. In time, it became an apartment house. Today the building, recently refurbished, bears no hint of its proud lineage.

Convention site 3/4 view

Site of the January 10, 1855, woman's rights convention that featured Susan B. Anthony and Ernestine L. Rose.

Convention site front view

Front view of the former Penn Yan Wesleyan Chapel, site of an 1855 woman's rights convention.

Associated Causes

Associated Historical Events

Woman's Rights Convention in Penn Yan

January 10, 1855