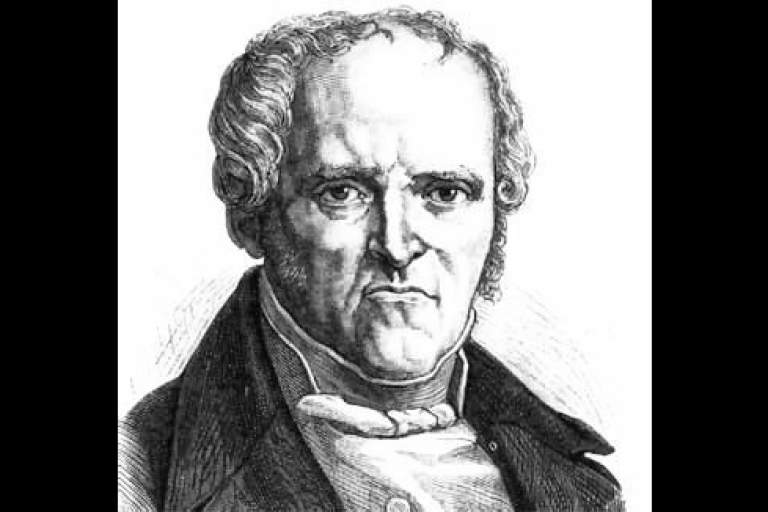

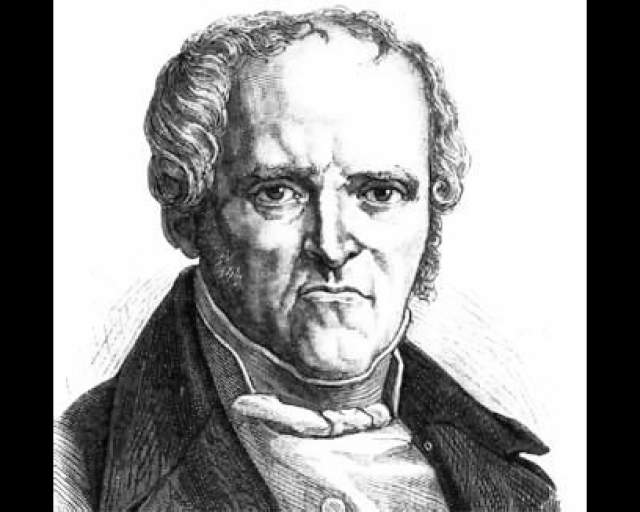

One of the oddest phenomena ever to sweep America was Fourierist Utopianism. In the wake of social shocks including the large-scale movement of rural populations to industrial cities and the financial Panic of 1837, reformers across the youthful nation were smitten by the peculiar theories of the French thinker François Marie Charles Fourier (1772–1837) (pictured).

In 1821, Fourier had published his influential book, A Treatise on Domestic and Agricultural Association. In it, he advocated for communities organized into “phalanxes” freed from private ownership in order to provide economic comfort, social justice, and individual fulfillment while resolving the differences among capital, management, and labor. Phalanx was the English term for a Fourierist community, transliterated from the French phalanstère, a coinage by Fourier that combined the French words phalange (phalanx, a basic ancient Greek military formation) and monastère (monastery).

Fourier’s theory of “attractive labor” held that all work, whether craftwork, industrial labor, or farm work, could be achieved free of the evils of capital and private property when individuals come together, each following his or her natural proclivities. None of this was based on experiment, nor on any concrete life experience of Fourier’s; it simply sprang from his brain—as did his conviction that phalanx life should include free love, which nonetheless led him to an early defense of woman’s rights. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) Fourier also proposed a complex mystical cosmology, jarringly predicting that when the perfect society was achieved the seas would (literally) lose their salt and turn to lemonade!

Even so, Fourier’s thinking struck a surprising chord among social radicals. According to historian Arthur Eugene Bestor, Jr., Fourierism briefly "established itself as one of the leading theories of social reform in the United States." The 1840s saw no fewer than three hundred attempts to build Fourierist "intentional communities" across America—intentional in the sense that members entered into relation with these communities by deliberate choice. That contrasts sharply with someone's relation to, say, one's family or native region, which is unintentional, unchosen—usually determined by accident of birth.

Few purported Fourieriest communities followed Fourier’s principles closely; even fewer interpreted them in the same way. But most involved some degree of communalism, whether in the form of shared labor or something more radical, such as sexual access to one another’s spouses. Most survived for a maximum of three years.

The first Utopian intentional community in America was New Harmony, an Indiana commune founded by reformer Robert Owen in 1824. This pre-Fourierist community was founded on freethought principles; pioneer feminist and freethought lecturer Frances Wright spent time at New Harmony, which was also the site of the first nineteenth-century experiment in dress reform. New Harmony failed in 1827.

The first Fourierist community in America was the famous Brook Farm at West Roxbury, Massachusetts. It was launched by a Shaker group in 1841 and continued until 1849, making it one of the longest-lived Fourierist experiments. As noted above, hundreds more followed. Most had some religious basis, whether traditional Christianity or some enthusiastic sect such as the Shakers or the Perfectionists.

Only two Fourierist intentional communities were wholly or significantly based on freethought principles: the Skaneateles Community and the Sodus Bay Phalanx. Both were founded in west-central New York State late in 1843 and failed within three years. (See the Rise and Fall of Skaneateles Community and the Rise and Fall of Sodus Bay Phalanx.)

By fall 1846, no Fourierist community—religious or otherwise—survived between Rochester and Syracuse.

Many intentional communities of this era featured economic, social, or sexual practices that former members—and, later, their descendants—would find scandalous or shameful. For that reason, the history of the Fourierist craze of the 1840s is often difficult to uncover because records were deliberately destroyed by descendants and sympathetic archivists.

Freethinking Fourierism in West-Central New York: A Timeline

| 1821 | Frances Marie Charles Fourier (1772–1837) publishes his magnum opus, A Treatise on Domestic and Agricultural Association, urging a new and wholly idiosyncratic way of organizing communities along cooperative lines. |

| 1831 | Fourier launches a movement newspaper, Phalanges. |

| Beginning in 1841 | In the wake of the Panic of 1837, groups across America agitate to form Fourierist communes. None implement all of Fourier’s principles; many seem not to understand or simply to ignore much of what Fourier ordained. Nonetheless, the movement gives rise to some 300 communities during the 1840s, few of which survive the decade. Most last three years or less. Most are religious, whether traditionally Christian or associated with some enthusiastic sect (Shakers, Perfectionists); only two are wholly or strongly of a freethinking character. |

| August 1841 | A Shaker group launches the first intentional community influenced by Fourierist principles at Brook Farm (West Roxbury, Mass., 1841–1849). |

| Spring 1843 | Preliminary meetings are convened at Skaneateles and Syracuse by clergyman-turned-atheist John Anderson Collins with the goal of founding a (distantly) Fourierist community at Skaneateles. (Collins is still in the employ of a national abolitionist organization headquartered in Boston, whose leaders think Collins is focused entirely on abolition work while in west-central New York.) |

| May 1843 | The Skaneateles Community is formed as a joint stock association. Hezekiah Joslyn, father of the future women’s-rights leader Matilda Joslyn Gage, is among the members of a small committee charged with vetting early applicants to purchase shares in the Skaneateles Community. |

| July 30, 1843 | Frederick Douglass lectures on abolition at Fayette Park in downtown Syracuse, an event organized by John Collins. Douglass is dissatisfied by Collins's focus on Fourierist utopianism instead of abolitionism. After Douglass complains to Collins’s superiors, Collins breaks from the abolitionist movement to pursue work on the Skaneateles community full time. |

| August 1843 | At Skaneateles, John Collins purchases for $15,000 the 300-acre farm at "Long Bridge" formerly owned by Elijah Cole. |

| August 17, 1843 | At a meeting at Syracuse's Unitarian Chapel, John Collins and other organizers inform the public that the Skaneateles farmstead will be the site of a (formally) Fourierist community. |

| August 22, 1843 | The Fourier Society of the City of Rochester holds its first convention. The prominent Hicksite Quaker Benjamin Fish, current president of the Fourier Society, is also elected president of the Ontario Phalanx, envisaged as a large Fourierist community serving the entire region. |

| October 14, 1843 | The formal launch of the Skaneateles Community. A general convention is held in the barn on the property. John Collins speaks, as does atheist firebrand Ernestine L. Rose. A young Matilda Joslyn Gage, aged 18, attends this meeting with her parents, Hezekiah and Helen Joslyn, who still plan to join the Community. |

| November 19, 1843 | John Collins publishes radical "articles of disbelief" for the Skaneateles Community espousing atheism, free love, rejection of government authority, the renunciation of private property, and the like. Hezekiah Joslyn and several others consider this too extreme and abandon the project. The Skaneateles Community becomes known in the region as “No God.” |

| November 21, 1843 | The Fourier Society of the City of Rochester meets at the Athenaeum, an important downtown meeting hall. It passes a resolution urging all who are interested in launching Fourierist communities to form “Auxiliary Societies” to launch small communities of their own. This runs contrary to the advice of Albert Brisbane, perhaps America’s leading Fourierist, who counsels that each region should have a single, large phalanx. (This advice is followed, essentially, nowhere.) |

| December 1843 | The Ontario Phalanx schisms bitterly over where to locate its community. One faction prefers the Shaker Tract on Sodus Bay in Wayne County, the other a location in Clarkson, northwest of Rochester. This drastically slows member recruitment. The Fourier Society of Rochester dissolves. |

| January 1844 | A visitor published a report on the Skaneateles Community stating that it is in fine order with cultivated fields, orchards, woods, several buildings, a stream, and a sawmill. The report adds that the Community comprises about ninety members who seem healthy and content. |

| January 1844 | A rump group of the Ontario Phalanx, including Benjamin Fish, purchases the Shaker Tract on Sodus Bay and launches the ill-fated Sodus Bay Phalanx. Supporters of the alternative site at Clarkson schism again, establishes small, equally doomed phalanxes at both Clarkson and North Bloomfield. |

| January 1844 | At the Sodus Bay Phalanx, meat-eating believers and largely vegetarian freethinkers clash repeatedly over food preferences as, more substantively, over whether labor should be permitted on Sundays. |

| January 1844 | Communal operations began at Skaneateles. |

| January 23, 1844 | The Sodus Bay Phalanx publishes a prospectus and constitution in the Rochester Republican newspaper. Benjamin Fish is noted as a leader; the prospectus names early nonresident members including Isaac and Amy Post and Huldah Anthony, cousin of Susan B. Anthony. |

| Spring 1844 | The American Industrial Union is launched at Rochester to promote three area phalanxes. Theron C. Leland opens an office in Reynolds Arcade where he offers information on the participating phalanxes and solicits subscriptions to their stock. |

| March 1844 | The Sodus Bay Phalanx begins operation on the 1400-acre Shaker Tract in Wayne County. It has about 300 members, many of them women and children. |

| June 1844 | D. C. Bloomer, the husband of woman’s rights activist Amelia Bloomer, visits the Sodus Bay Phalanx and comments on its startling religious diversity. Beneath the surface, religious conflicts have already begun tearing the community apart. |

| July 1844 | Ten members are abandoning Sodus Bay Phalanx each month. |

| August 1844 | One devout Sodus Bay Phalanx member brings a formal complaint against two freethinking members for working in a field on the Sabbath. The case is weighed by the Phalanx’s entire board of directors, which votes 4–3 to acquit the freethinkers. |

| September 1844 | Conflict spikes at Sodus Bay. Ten members give notice of their intent to abandon the Phalanx in a single two-week period. By month’s end, the more religious members of the community have abandoned it, taking with them what of their property they could and a bit more besides, leaving the remaining freethinkers bereft of essential resources. |

| October 1844 | The failing Sodus Bay Phalanx adopts a new constitution. Oddly, it is the first in the community's history to mention the key Fourierist principle of series. The new constitution does nothing to arrest the Phalanx’s decline. |

| December 9, 1844 | The Phalanx, a national Fourierist newspaper, concedes that the Sodus Bay Phalanx is failing, in “a striking example of the folly of undertaking practical Association without sufficient means, and without men of proper character.” |

| April 7, 1845 | The Sodus Bay community adopts yet another new constitution and renames itself the Sodus Phalanx. |

| May 1845 | Robert Owens visits Skaneateles Community for four days, reporting favorably on what he sees there. Yet that community, too, is on the verge of failure, mostly because it depends too heavily on future revenue to meet current needs. |

| May 21, 1845 | John Collins publishes an article in the Skaneateles Community’s newspaper, The Communitist, essentially conceding that the community is failing. |

| September 1845 | Correspondent Lorenzo Marrett writes to The Harbinger, another Fourierist paper, reporting that the Sodus Bay Phalanx still functions, albeit with only “twelve to fifteen adult males” and little prospect of paying its remaining debts. |

| February 1846 | In a desperation move, the Skaneateles Community petitions New York State for permission to incorporate as a municipality. The State Legislature denies the petition. |

| April 4, 1846 | Dissolution of the Sodus Bay Phalanx is announced. Benjamin Fish serves on committee to conclude the community’s remaining business. |

| April 17, 1846 | The committee completes its work, distributing the Sodus Bay Phalanx's remaining assets. |

| April 30, 1846 | The Columbian, a Skaneateles newspaper, editorializes that the Skaneateles Community is collapsing because “the bonds of infidelity are not suited to hold men together in social harmony.” |

| May 1846 | John Collins calls a meeting, announces the failure of the Skaneateles Community, resigns as its leader, and quickly vanishes. |

| August 1846 | A correspondent sights John Collins in Dayton, Ohio, where he is publishing a Whig newspaper. |

| September 1846 | By this time, every phalanx in the greater Rochester area has failed. |

| Sometime in 1847 | Two lecturers from Brook Farm in Massachusetts visit west-central New York. They find the entire Syracuse area hostile to their cause because the Skaneateles Community has given Fourierism a bad name. |

| Sometime in 1850 | John Collins sells the Skaneateles property to Samuel Sellers, a former community member. |

| Sometime in 1853 | John Collins runs as an independent for governor of California. He is unsuccessful. |

| Sometime in 1865 | A Syracuse man spots John Collins while visiting California; he is working as a land promoter. |

| December 1885 | John Collins appears in New York City, where he lectures on geology, a field in which Collins was not previously known to be expert. |

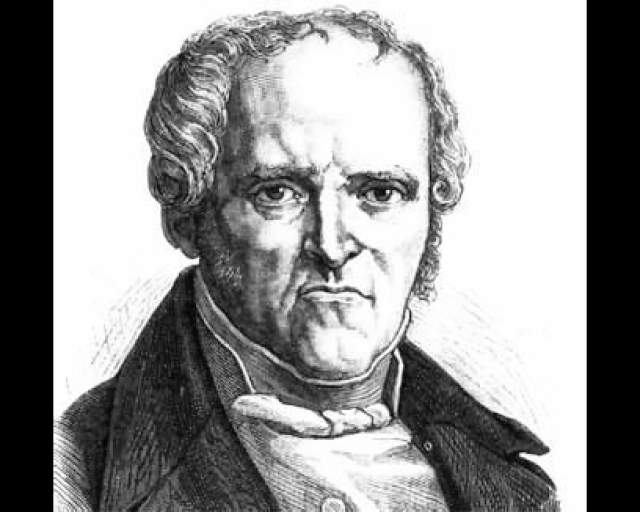

François Marie Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier, whose eccentric philosophy inspired an American craze for communal living.

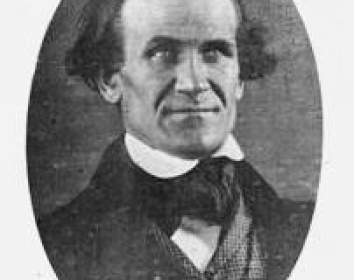

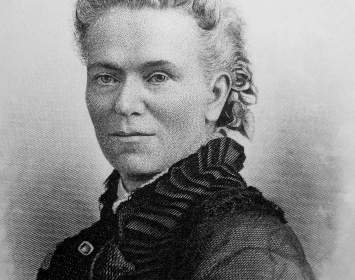

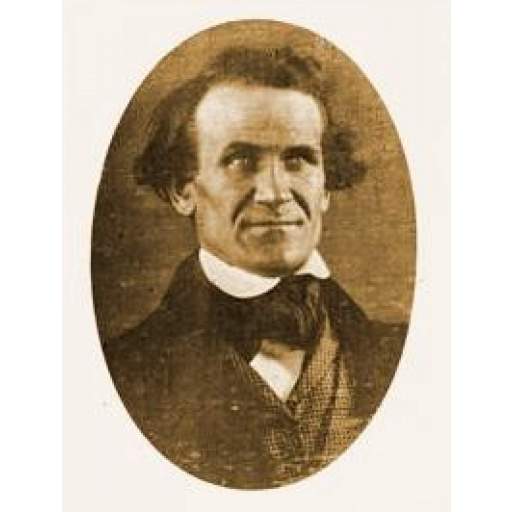

John Anderson Collins

John Anderson Collins (birth and death dates unknown) promoted an ill-fated, putatively Fourierist community at Skaneateles. Undercapitalized and riven by controversy between religious and freethinking members, the commune failed in less than three years.

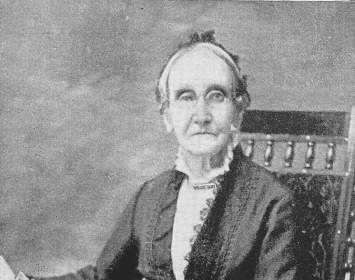

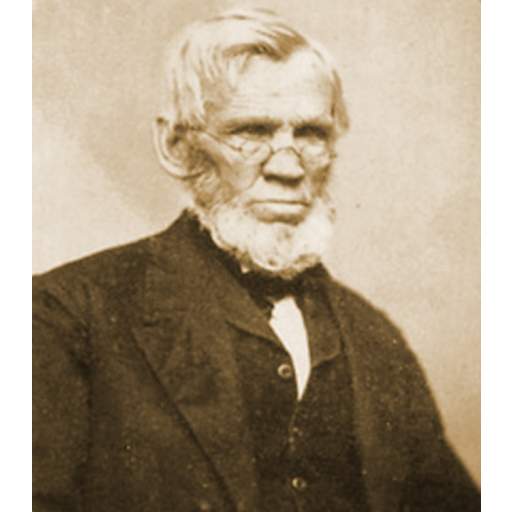

Hezekiah Joslyn

Hezekiah Joslyn (1757-1865), father of the future suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage, worked on organizing the Skaneateles Community and planned to move to the intentional community with his family, including the then-teenaged Matilda, before being put off by the erratic behavior of lead organizer John Anderson Collins.

Associated Historical Events

First Convention of the Fourier Society of Rochester

August 22–23, 1843

Meeting of Fourier Society of Rochester

November 21, 1843

Rise and Fall of Sodus Bay Phalanx

1843–1846

Rise and Fall of Skaneateles Community

1843–1846