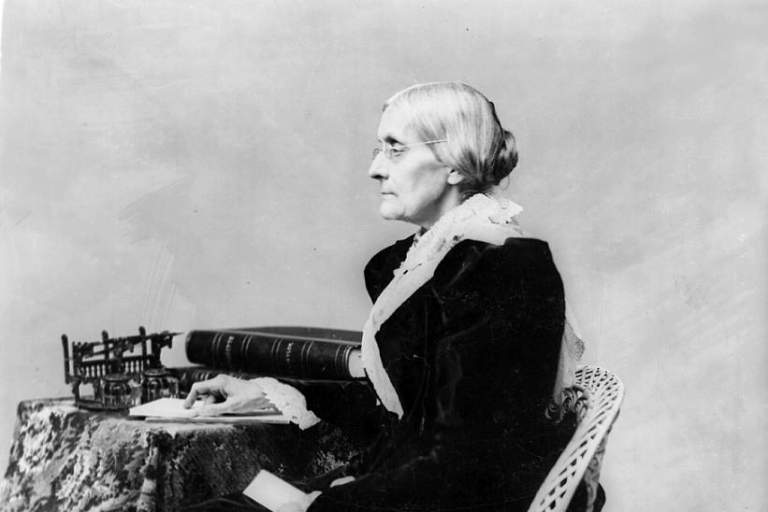

On June 18, 1873, suffrage pioneer Susan B. Anthony was tried on the charge of voting illegally in the U.S. presidential election of 1872. (That Anthony had voted was never in question; she and fourteen other women had voted publicly, in Rochester, on November 1, 1872. Moreover, immediately after voting Anthony had given a newspaper interview recounting her successful effort to vote.)

Anthony was arrested on November 18, 1872, for violating the federal Enforcement Act of 1870, which provided in part that “Any person … who shall vote without having a legal right to vote … shall be deemed guilty of a crime.”

Anthony went to trial on June 18, 1873. She had made so many pro-suffrage speeches in Monroe County, where Rochester is located, that the trial was moved to the Ontario County Courthouse in Canandaigua. Anthony was tried before Judge Ward Hunt, who had just been named to the U.S. Supreme Court. A politician who had held elected judgeships and was a close associate of New York power broker Roscoe Conkling, Hunt had never presided over a criminal trial.

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) sent no official representative to the trial. Matilda Joslyn Gage, then an NWSA officer, attended the trial in her personal capacity to show Anthony support.

The trial lasted three days and ended in controversy. Justice Hunt had written his decision prior to the trial. Rather than allow the jury to deliberate, he instead directed it to return a guilty verdict. He ordered the court clerk to enter that verdict immediately and fined Anthony $100. Hunt then routinely requested whether Anthony had anything to say. Anthony responded with a lengthy and impassioned speech condemning the trial and Justice Hunt’s conduct. Ignoring Hunt’s repeated commands to be quiet, Anthony thundered that Hunt had “trampled under foot every vital principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored.” Anthony concluded, “I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty.” Under the law of the day, Anthony could have appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court only if Hunt had ordered her jailed until she paid the fine. Hunt prudently declined to do so, leaving Anthony with no avenue for appeal.

The trial received extensive media coverage. Daily reports by the Associated Press appeared in newspapers across the nation, and editors wrote prolifically on both sides of the controversy. When the drama subsided, the trial had further cemented Anthony’s stature as a suffrage leader and thrust the suffrage movement even more prominently into national attention.

Anthony never paid the $100 fine. In January 1874, she petitioned the U.S. Congress to remit her fine, arguing that Hunt’s use of the so-called directed verdict had been grossly improper. The Senate and House Judiciary Committees both debated the issue. A bill to remit the fine reached the House floor but did not pass.

Despite cursory subsequent efforts to collect the fine, Anthony never paid a penny of it.

The fourteen other women who had voted with Anthony were arrested and indicted, but U.S. Attorney Crowley opted not to try them. The election inspectors—whom Anthony’s rhetoric had persuaded to let the women vote—were tried, immediately after Anthony’s trial. They were found guilty of violating the Enforcement Act and fined; refusing to pay the fine as Anthony had, they were jailed. Anthony and others campaigned for their release, a cause taken up by some members of Congress. On March 3, 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant pardoned the inspectors. By now quite popular in Rochester, they were immediately re-elected to their posts.

Susan B. Anthony discouraged talk of a pardon during her life; she viewed the conviction as a badge of honor. She was pardoned, however, on August 18, 2020, by President Donald J. Trump.

Justice Hunt’s directed verdict provoked years of legal controversy. In 1895, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Sparf v. United States that federal judges could not order a jury to return a guilty verdict in a criminal trial.

The courthouse bears no historic marker commemorating the trial, but a bust of Susan B. Anthony is displayed outside the courtroom entrance and a portrait of Anthony hangs in the courtroom.

Thanks to Edward Varno for research assistance. Special thanks to Deputy County Administrator Brian Young for site access for photography.

Ontario County Courthouse

Ontario County Courthouse stands on high ground overlooking a principal highway in Canandaigua, New York. The upper floor with its taller windows contains the courtroom where Susan B. Anthony was tried. Municipal offices coveted for their views occupy the base of the cupola (windows above front pediment).

Courtroom in Which Susan B. Anthony Was Tried

An ambitious 1987 - 88 renovation restored this grand courtroom to its late-eighteenth-century appearance. Its walls bear numerous portraits of influential judges and community leaders -- and a portrait of Susan B. Anthony.