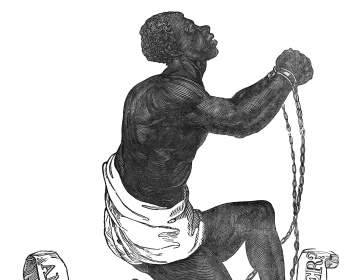

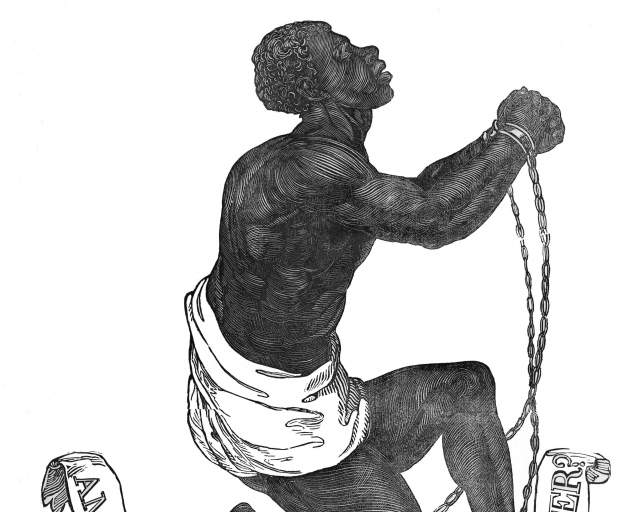

In 1852, the building now known as Oswego's Old City Hall was the Market House, a public hall that provided space for merchants, village offices, meetings, and occasional theatrical presentations. There, on October 2, 1852, the National Liberty Party held its national convention, nominating two prominent abolitionists: Gerrit Smith for president and Samuel Ringgold Ward for vice-president. Ward was the first African American nominated on a presidential ticket by a national political party.

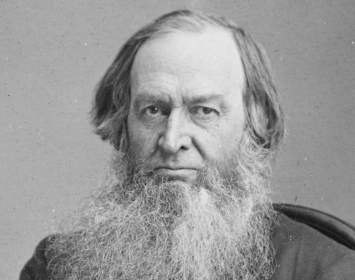

All of which was less impressive than it might sound. The National Liberty Party was a vestige of the Liberty Party, a minor party that had exerted modest influence in the elections of 1840 and 1844 and a lesser influence in the election of 1848. The Liberty Party had been envisioned in January 1840 as a means of running candidates for office pledged to abolish slavery. That February, Gerrit Smith had met with abolitionists William Goodell and James G. Birney at Smith's estate in Peterboro, New York. (Smith was a multimillionaire and philanthropist who generously supported the causes he embraced.) They laid plans to form an independent antislavery party, which was formalized at an April 1 convention in Albany. Beginning in 1845, the Liberty Party suffered internal dissension over issues including whether to embrace a broader reform agenda or remain solely focused on abolition. (Goodell advocated broadening the party's agenda; Smith opposed it.)

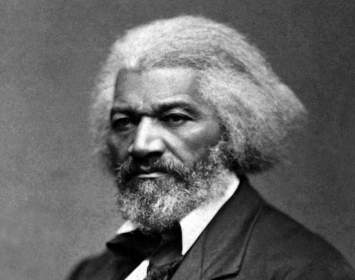

In 1847, Smith, Frederick Douglass, and others created the Liberty League, originally intended as a special interest group within the Liberty Party that would maintain an exclusive focus on abolition. By June of that year, at a convention held in Macedon Lock (now Macedon), the Liberty League reorganized as a political party in its own right, again committed to the pure abolitionist agenda.

By the 1848 campaign, the Liberty Party was already a shell of its former self. In New York, some four-fifths of its members had abandoned it for the fast-growing Free Soil coalition, whose agenda included ensuring that newly acquired U.S. states and territories would not permit slavery. Still, what remained of the Liberty Party ran William Goodell for president, while the Liberty League ran Gerrit Smith. Yet Smith was still dissatisfied; in mid-June 1848, he presided over the founding of yet another abolition party, the National Liberty Party. (This party endorsed the Liberty League ticket; in September the Liberty League and the National Liberty Party held a joint convention in Canastota to pool their admittedly minimal influence.)

The 1848 election was a debacle for all three antislavery parties; Smith received only 2,733 votes across all his ballot lines, and only 188 of those came from outside New York. Goodell and the Liberty Party ticket did little better. The Liberty Party and the Liberty League essentially dissolved, leaving only a tiny splinter, the National Liberty Party, to continue fielding pure abolitionist candidates. (For more on this history, see Gerrit Smith's biography page.)

Such was the National Liberty Party that convened in Oswego in October 1852. (It is another measure of the party's impotence that it set to nominating its presidential slate just one month before the election.) Nonetheless, it was Gerrit Smith's fourth and final presidential nomination by a bona fide party. Yet he seemed not to take it too seriously; he never campaigned and reportedly asked some of his friends not to spend their votes on him. Instead, he mounted a last-minute independent candidacy for Congress, which he won—perhaps not surprisingly, in view of his immense stature in his home district. (He found Congress disagreeable and resigned halfway through his first term.)

Though the Liberty Party, Liberty League, and National Liberty Party failed to get any candidates elected—the usual fate of minority parties in the American system—the three parties are nonetheless significant. As vehicles for protest, they shifted Northern political opinion toward abolition and smoothed the way for emergence of the Republican Party that elected Abraham Lincoln.

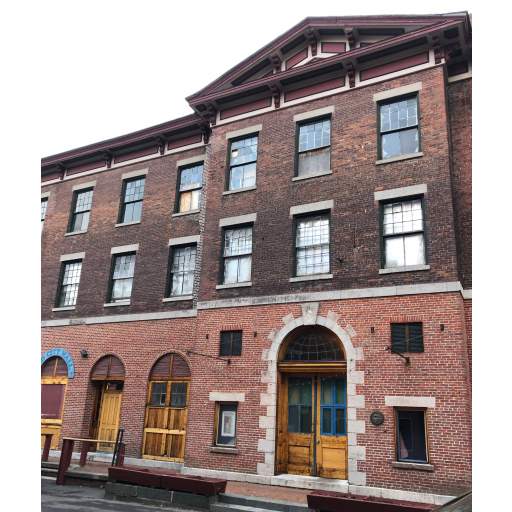

The Building and Site. This building was constructed in 1836 under the authority of the village council at a cost of $17,777.09. Its design was based on that of a hall of similar purpose recently erected in Albany, New York. As was common at the time, it was a multiple-use structure including merchant stalls, government offices, the Post Office, and meeting space. Rental income provided revenue—even the village jail paid rent. In 1844, an addition was built on the building's south side to serve as a fire station. In 1848, when Oswego became a city, it was formally named City Hall. In 1864, railroads having become increasingly central in the booming port community, the building was sold to the Lackawanna Railroad Company. The city continued to rent space for government offices, a courtroom, and the like until the construction of a new municipal building. That larger masonry structure was designed by prominent Syracuse architect Horatio Nelson White, and opened late in 1871. During the twentieth century the older building housed varied tenants including a business college, a ship chandlery, assorted wholesale merchants, and the Oswego Board of Trade. Late in the twentieth century the building was taken over by Old City Hall, a popular restaurant and live-music venue that remains open today.

Old Oswego City Hall

A public market in Gerrit Smith's day, this building later served Oswego as its city hall. Today it's a nightlife center. Photo by Haley Karr.

Another view of Old City Hall

Alternate view of Oswego's Old City Hall. Photo by Haley Karr.

Associated Causes

Associated Historical Events

National Liberty Party Convention

October 2, 1852