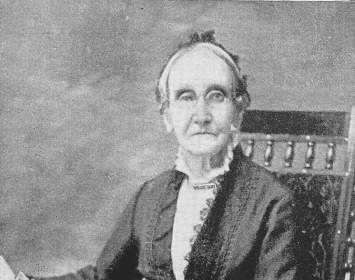

On August 2, 1848—just two weeks after the historic first woman's rights convention held at Seneca Falls—a follow-on convention was held in Rochester's Unitarian Church. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) Rochester abolitionist and feminist Amy Post organized the event and called the meeting to order. Rochester abolitionist Abigail Bush was elected to preside, the first time that a woman was elected president of a public meeting open to both sexes. This was so radical a step that, amazingly, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, two organizers of the Seneca Falls convention, walked off the platform in protest when Bush took the chair! (Apparently Bush discharged her responsibilities successfully, and future woman's rights meetings were quite frequently presided over by women.) One of the event's three secretaries was the abolitionist Catherine Fish Stebbins, daughter of the abolitionist and failed Utopian Benjamin Fish. Like many who attended the Rochester convention, Stebbins had been present at Seneca Falls.

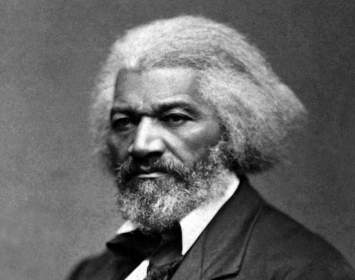

Among those attending were the prominent antislavery campaigner Frederick Douglass and Sarah D. Fish, mother of Stebbins, who delivered an address to the convention. (Like her daughter, Sarah Fish had attended the Seneca Falls convention. She was also one of three women—the others being Amy Post and Sarah Hallowell—who suggested electing a woman to preside over the convention.)

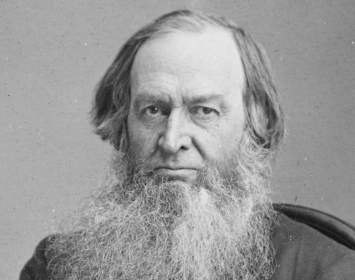

A congratulatory letter from philanthropist and woman's rights advocate Gerrit Smith was read from the platform.

The convention passed a series of resolutions, including:

"… it is an admitted principle of the American Republic, that the only just power of the Government is derived from the consent of the governed; and that taxation and representation are inseparable; and, therefore, woman being taxed equally with man, ought not to be deprived of an equal representation in the Government."

"… we deplore the apathy and indifference of woman in regard to her rights, thus restricting her to an inferior position in social, religious, and political life, and we urge her to claim an equal right to act on all subjects that interest the human family."

"… the universal doctrine of the inferiority of woman has ever caused her to distrust her own powers, and paralyzed her energies, and placed her in that degraded position from which the most strenuous and unremitting effort can alone redeem her."

The full set of resolutions adopted by the Rochester convention was reproduced in an appendix of the first volume of The History of Woman Suffrage, authored by Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage. (The whole of Volume I is available here; the Rochester Resolutions begin on page 808.)