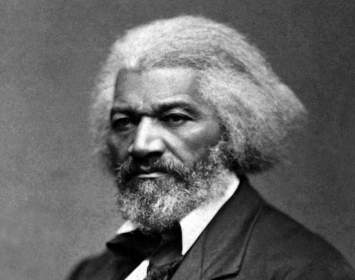

In June 1847, Gerrit Smith, Frederick Douglass, and others organized a convention at an unknown venue near the Erie Canal locks in Macedon, New York. At this convention the abolitionist Liberty League, a radical splinter group of the Liberty Party, organized itself as a full-fledged rival political party. (The Liberty Party had performed disappointingly in the presidential election of 1844, and there were growing disputes over its future direction.) The precise location of the convention—even whether it was held indoors or outdoors—remains unknown.

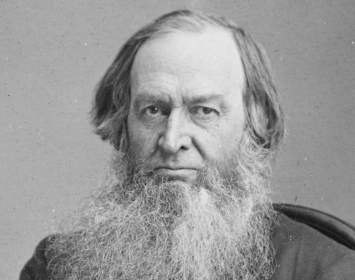

As early as 1846, Smith was dissatisfied with the Liberty Party, which he called “a poor, erring, half-hearted party.” In this he was not alone; activists such as William Goodell sought an antislavery party that would involve itself in other national issues in addition to slavery. (Smith disagreed with that strategy but found the Liberty Party insufficiently radical.) In June 1846, at a meeting at an unknown site in Farmington, Liberty Party dissidents initially formed the Liberty League. At that point the League was viewed not as a schismatic party but as a focus for more intensive promotion of the antislavery cause. Largely, this reflected Smith’s reluctance to launch a new party.

By June 1847, Smith’s attitude had changed. In part he was influenced by Goodell, who feared—correctly, as matters developed—that the Liberty Party was losing its focus and drifting toward absorption into the Free Soil movement. The League took firm positions on ending the then-ongoing Mexican-American War, ending all tariffs and restraints on trade, barring holders of liquor licenses from public office, and land reform. It echoed Smith's conviction that no legislation was needed to end slavery because the U.S. Constitution already implicitly forbade it. Finally, the Liberty League advocated woman suffrage, the first American political party to do so. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's.)

The convention was held on June 8, 1847. Goodell presided. Seventy persons attended. Smith received the new party’s presidential nomination for the 1848 campaign. The vice-presidential nod went to Massachusetts peace activist Elihu Burritt. Burritt was not present at the convention and refused the nomination when he learned of it. Michigan Underground Railroad conductor Charles C. Foote was later nominated in Burritt’s place.

It is known that Smith attended the convention; it is surmised that Douglass did too. Also thought to be present were the abolition and woman's rights activists Lydia Maria Child and Lucretia Mott; each woman received a vote in early balloting. Women present were permitted to vote on nominations, a first in American politics; the votes for Child and Mott marked the first time in history that women received votes for president of the United States at a bona fide political convention.

As noted, the convention's precise location is unknown. Contemporary accounts are clear in referring to the site as “Macedon Lock,” though there is no community by that name and never was.

It is possible that the convention was held outdoors, within sight of the double-chambered canal lock that then served the enlarged Erie Canal. If so, then the location was probably within the boundaries of today’s Macedon Canal Park.

Lock 30, Macedon, N. Y.

Present-day Lock 30, built around 1914. Remains of the previous, double-chambered lock, which would have been standing at the time of the Liberty League Convention, lie about 100 feet south of camera position (behind photographer), obscured by thick undergrowth.

Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Child (1802 - 1880) was an abolitionist, women’s rights activist, freethinker, and journalist. She and Lucretia Mott were the first women to receive a vote for president of the United States at a bona fide political convention.

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (1793 - 1880) was a Quaker abolitionist and feminist who helped plan the 1848 woman’s rights convention at Seneca Falls. She and Lydia Maria Child were the first women to receive a vote for president of the United States at a bona fide political convention.