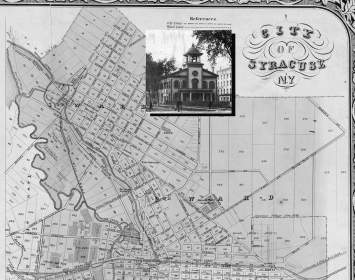

The 1848 Woman’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls had been followed in 1850 by the first in a series of annual conventions designed to raise the profile of the woman’s rights movement. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) This event took place at Worcester, Massachusetts. The second annual convention (1851) was held in Worcester also. On September 8–10, 1852, the Third National Woman’s Rights Convention was held in Syracuse at the newly named City Hall. A capacity crowd—two thousand people from eight states and Canada—attended. Because the site was nearer to Seneca Falls than Worcester had been, a record number of delegates who had signed the Declaration of Sentiments adopted at Seneca Falls were able to attend.

The tone for the convention was set by poet and activist Elizabeth Oakes Smith, who told attendees that "our aim is nothing less than … that every American citizen, whether man or woman, may have a voice in the laws by which we are governed." Lucretia Mott, one of the Quaker co-architects of the Seneca Falls convention, was elected president of the Syracuse convention. At one point, Mott was compelled to silence a minister who insisted on presenting Biblical justifications for women’s subordination to men. A letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read aloud, and resolutions it contained were voted on.

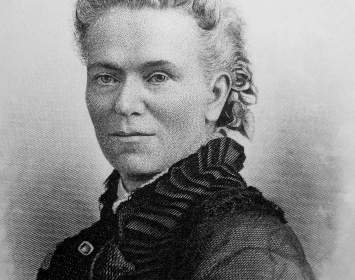

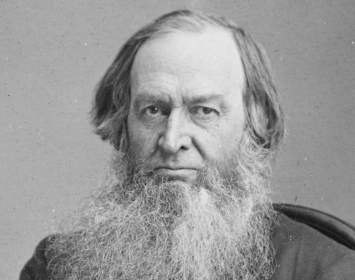

The Syracuse convention’s most noteworthy aspect may be that it was the first public woman's rights event attended by both Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage. Anthony participated, but did not speak; Gage made her first public speech on woman’s rights at this event. Gage stated, in part: "I do not know what all the women want, but I do know what I want myself, and that is, what men are most unwilling to grant; the right to vote." Lucy Stone made her first public appearance in the "Bloomer" costume invented by Elizabeth Smith Miller and popularized by editor and reformer Amelia Bloomer, whose name came to be attached to that style of "reform dress." Atheist and woman’s rights activist Ernestine L. Rose also spoke. For his part, Peterboro philanthropist Gerrit Smith gave his first public speech on woman's rights at this event.

The Syracuse Convention may be best remembered for what it did not accomplish: it did not lead to the creation of a permanent, national organization to advocate for the rights of women. After a motion along these lines was rejected, Miller urged the formation of state-level organizations, but that too was rejected out of fears that a permanent organization might sow divisiveness or limit the creativity and spontaneity of activists. No national women’s organization would be formed until after the Civil War.

A transcript of the convention proceedings is available here.

Thanks to Norman Dann for research assistance.