Dress Reform Sites

Custom

123.0 Miles

This trail extends from Seneca Falls on the west to Peterboro on the east. Unmarked sites are omitted; all sites on this list include a historical marker, a historic structure, or a museum. Visitors seeking a shorter curated experience might wish to visit the Seneca Falls sites, which are extremely content-rich, in one outing and the Oswego and Peterboro sites on a second journey. The Peterboro sites have limited hours; call ahead or check online.

Given the constricting excess of middle-class women’s clothing in nineteenth-century America, it is hardly surprising that reformers strove to promote more practical clothing styles so women could be more active outside the home. Woman’s rights (nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's) campaigners from west-central New York State were not the first to seek reform in this arena, but they were among the most prominent.

So-called "reform dress" began with trousers for women, first adopted at a Utopian commune in New Harmony, Indiana, in 1824. New Harmony failed in 1827. In 1848, the Christian Perfectionist Oneida community of Oneida, New York, resurrected reform dress, this time featuring short dresses over pantaloons. Similar initiatives were taken at other non-freethinking intentional communities.

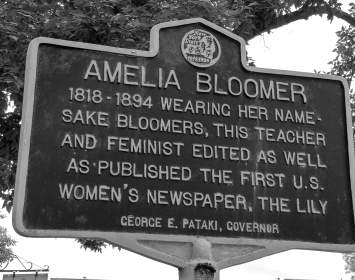

But the iconic period of reform-dress activism occurred among woman’s rights and suffrage activists in west-central New York. Early in 1851, Elizabeth Smith Miller of Peterboro, the daughter of abolitionist philanthropist Gerrit Smith, designed the definitive reform-dress style: a roughly knee-length skirt worn over Turkish-style pantaloons. The style was worn in public by Miller and by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Jencks Bloomer, both of Seneca Falls. Bloomer, editor of the temperance and woman’s-rights paper The Lily, promoted the costume vigorously. The new mode of reform dress set off a media firestorm; reporters eager for a catchy name dubbed it “the Bloomer costume.” The name stuck, though Amelia Bloomer had only promoted the fashion.

Concerned that the Bloomer costume was becoming a distraction from the real world of campaigning for votes for women, suffragists gradually abandoned it. Even Elizabeth Smith Miller stopped wearing “Bloomers” after 1861. The style was then taken up among practitioners of water cure (hydropathy), a then-popular quack therapy involving mineral-water or steam baths and pure foods, often administered in a residential sanitarium setting. A Central New York hydropathist founded the National Dress Reform Association (NDRA), which held periodic conventions and issued a newspaper, The Sibyl. An 1857 convention in Canastota was attended—and probably funded—by Gerrit Smith. The NDRA continued for several years, but neither it nor The Sibyl would survive the Civil War years.

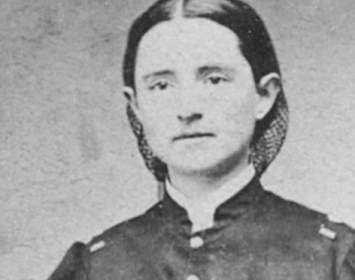

Independent from the dress reform movement as such was Dr. Mary Edwards Walker (1832–1919), a dress reformer, feminist, and freethinker. She was a vice president of several NDRA conventions. By then she had already earned a medical degree and begun wearing trousers. She became the first woman employed as a surgeon by the U.S. Army and in 1866 received the Medal of Honor, to this day the only woman so recognized. Walker continued to wear the Bloomer costume until the 1870s, when she abandoned it for the wardrobe she would prefer for the rest of her life: upper middle-class male attire, including trousers, coat, vest, and top hat.

"Among the crusades attempted by antebellum Americans, pantaloons dress reform had perhaps the narrowest appeal," wrote historian Gayle V. Fischer. Nonetheless, its chronicle adds a fascinating dimension to the Freethought Trail.