Amelia Jenks Bloomer was a social radical, a vigorous advocate for temperance, woman’s rights, and dress reform. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) But she was not a freethinker, remaining a believing Episcopalian all her life. Amelia cofounded and for seven years edited the nation’s first newspaper for and by women. However ironically, she is best known to history for a style of reform dress she did not design.

Amelia Jenks was born in 1818 at Homer, New York. Aged seventeen, she moved to Waterloo, New York, to live with a newly married sister. There she met Seneca Falls newspaper co-owner, law student, and local political activist Dexter Bloomer. Dexter and Amelia married in Waterloo on April 15, 1840. She was twenty-two. Their ceremony omitted the word obey, then a vigorous assertion of woman’s rights. The next day, the Bloomers took up residence in the Seneca Falls home of Isaac Fuller, Dexter’s partner in the Seneca County Courier. The newlyweds would abide there for almost six months.

Local oral tradition suggests that the Italianate-style building now standing at 53 East Bayard Street in Seneca Falls is the Fuller house. Research by the National Park Service in the mid-1980s has been unable to confirm it, but the association was taken seriously enough in 1980 that the house was added to the National Register of Historic Places as Amelia's dwelling place. On that account, the main dwelling was built in 1830. If this is true, the current house would be the same structure in which the Bloomers briefly resided. The account continues that the main building was significantly modified in the 1850s, then converted into a multiple unit dwelling in 1945. In addition to briefly housing the Bloomers, the house was said to have been a station on the Underground Railroad. (More recent research suggests that the house now on the site may not have been present in 1840.) Whether or not the Bloomers actually lived on the site, its popular association with Amelia is ironic, as her prolific reform work began only after she left the Fuller residence.

On October 1, 1840, the Bloomers moved to their own “modest dwelling” (Dexter’s words) in Seneca Falls. Its location is unknown, though a local tradition places it near the junction of Fall, Cayuga, and Ovid Streets (one block south of a present historical marker at Cayuga Street and Trinity Lane).

A Life of Activism. Amelia attended an 1840 lecture by visiting temperance advocates, thereafter beginning a life of reform activity. Her enthusiasm for temperance work was intense, as was her husband's. Dexter launched a short-lived temperance paper, The Water Bucket, to which Amelia contributed articles. For his part, Dexter continued editing the Courier, launched a successful law practice, and served one term as town clerk.

The famed convention that launched the nineteenth-century woman’s rights movement took place in the Wesleyan Chapel at Seneca Falls on July 19–20,1848. At that time, Amelia had not embraced the woman’s rights cause. She attended only one evening session of the convention and did not sign the Declaration of Sentiments it adopted. Still, the event apparently increased her interest in activism.

The Lily. One month after the Seneca Falls convention, at an August 1848 meeting of the local Ladies Temperance Society held in downtown Seneca Falls, Amelia suggested that the group publish its own newspaper. The proposal was adopted; Amelia was named one of two coeditors. The name The Lily was suggested by the society’s president. The publication would become the nation’s first newspaper edited by and for women.

The enterprise proved more demanding than most Temperance Society members had expected. One by one they abandoned the project; Amelia alone persisted. She later wrote: “I threw myself into the work, assumed the entire responsibility, took the entire charge editorially and financially, and carried it successfully through.” Amelia would own and edit The Lily for the next seven years. The paper transitioned from local distribution to national distribution by mail with several hundred paid subscribers.

In spring 1849, Dexter was appointed postmaster of Seneca Falls. He named Amelia his deputy. The exact location of the post office where they worked is unknown.

The Lily outgrew its roots in temperance, emerging as an audacious woman’s rights paper. In part this reflected the influence of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whom Amelia had befriended in the summer of 1849. Stanton wrote frequently for The Lily thereafter.

The Bloomers moved to a bigger house in Seneca Falls in 1850; its location is also unknown. The couple lived there for four years.

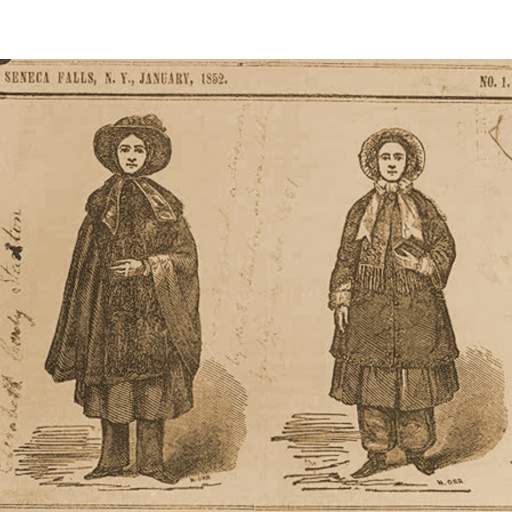

Dress Reform. Early in 1851, Elizabeth Smith Miller of Peterboro, New York, the daughter of abolitionist philanthropist Gerrit Smith, designed a style of “reform dress” comprising a roughly knee-length skirt worn over Turkish-style pantaloons. Accounts suggest that Miller wore this style while visiting Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Seneca Falls; Stanton immediately copied the garment. (At this time middle-class women made most of their own clothing.) Amelia was likewise inspired to create a reform costume in that style. Considering it far more practical and healthful than traditional women’s fashions, Amelia began to promote Miller’s version of reform dress in The Lily, including an illustration in the January 1852 issue that attracted press attention nationwide. The resulting controversy secured The Lily’s national reputation. Its circulation rose from 500 per month to over 4,000 per month.

The press gave the new style its name: the Bloomer Costume or, more simply, Bloomers. Though she had merely publicized the style, not designed it, Amelia became its namesake. It was widely adopted by woman's rights and suffrage advocates over the next several years.

Woman's Rights. On May 12, 1851, after attending an antislavery lecture by William Lloyd Garrison, Amelia introduced Susan B. Anthony and Stanton to one another on the streets of Seneca Falls. (Anthony had been staying with Amelia.) Thus were introduced two-thirds of the “Triumvirate,” the team (including also Matilda Joslyn Gage) that would lead the more radical, New York-based wing of the woman’s rights movement until 1890. (The event is commemorated in a 1998 sculpture by local artist Ted Aub displayed on the shore of Van Cleef Lake along Bayard Street, along the route between downtown Seneca Falls and Stanton’s painstakingly restored home. The sculpture depicts Amelia and Stanton wearing Bloomers.)

In the same January 1852 issue in which Bloomers were introduced, the slogan of The Lily was changed from "A Monthly Journal Devoted to Temperance and Literature" to "Devoted to the Interests of Woman." Amelia's emergence as a woman’s rights campaigner was complete. Despite Stanton’s influence, Amelia remained a Christian; The Lily never criticized the church for its views on women.

During 1853, Amelia, Susan B. Anthony, and other woman’s-rights leaders conducted a successful lecture tour around New York State. Amelia continued her activism on behalf of both woman's rights and temperance.

Beyond New York. In late 1853, the Bloomers left Seneca Falls for Mount Vernon, Ohio, where Dexter had acquired an interest in a local newspaper, The Western Home Visitor. Amelia continued to publish The Lily, whose circulation peaked at over 6,000 per month. Dexter would be less successful; the Visitor failed in 1854. In 1855, the Bloomers moved again, now to Council Bluffs, Iowa. The settlement was very much a frontier community. Unable to secure printing or reliable mail service, Amelia could no longer continue with The Lily. She sold the paper to Mary Birdsall of Richmond, Indiana. (The two had met at an 1853 National Woman's Rights Convention in Cleveland; Birdsall had edited the woman's section of an Indiana farming newspaper.) Amelia remained a contributing editor.

In 1858, long after most suffragists had given up Bloomers, Amelia finally set them aside for a new fashion, the light-weight wire hoop skirt. Only Elizabeth Smith Miller wore Bloomers longer, until as late as 1861.

Unfortunately, Mary Birdsall proved unable to duplicate Amelia’s publishing success. The Lily 's last known issue came out in February 1859.

Amelia remained active, serving as president of the Iowa Woman Suffrage Society from 1871–1873. She died of a heart attack, aged seventy-six, in 1894. She was buried beneath a handsome obelisk in Fairview Cemetery in Council Bluffs.

Amelia Bloomer Remembered. Amelia Jenks Bloomer is commemorated at four principal locations:

- The Ted Aub statue on Van Cleef Lake.

- The historical marker at Cayuga and Trinity Streets. The marker very briefly synopsizes Amelia’s life. Its location seems not to tie to either downtown Bloomer home or the location of the post office where Dexter and Amelia worked, but simply at a visible place on U.S. Route 20.

- The residence believed to be the Fuller House still stands but bears no marker specific to Amelia.

- Finally, Amelia’s role and the importance of the Bloomer costume is noted by a historical marker that stands besides Elizabeth Smith Miller’s onetime residence on the village square in Peterboro.

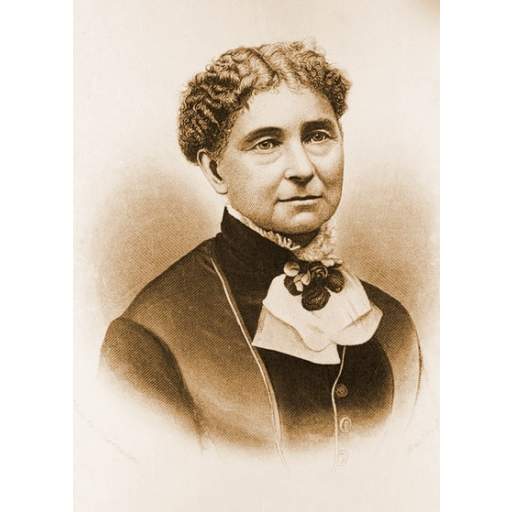

Amelia Jenks Bloomer

Amelia Jenks Bloomer.

Young Amelia Bloomer

Amelia Bloomer as a young woman.

Bloomer Costume

Illustrations of the reform costume published in The Lily in January 1852 stirred national controversy. The style came to be named "Bloomers"—after Amelia Bloomer who had publicized it, not Elizabeth Smith Miller who had actually designed it.

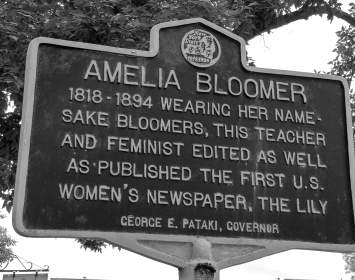

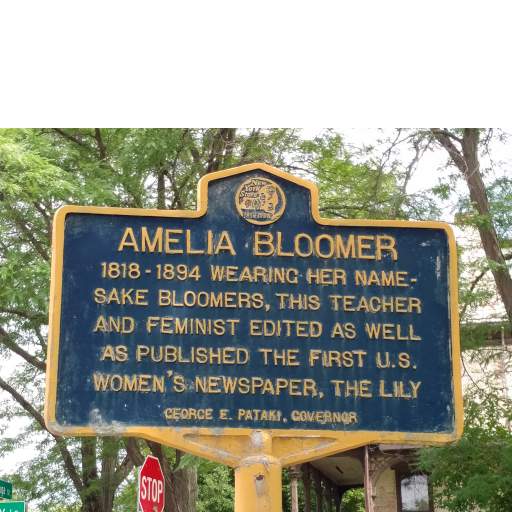

Amelia Bloomer Historic Marker

This historic marker at Cayuga and Trinity Streets in Seneca Falls summarizes Amelia Bloomer's life and contributions. Its location may correspond to either of the Bloomers' downtown residences or that of the post office where Dexter and Amelia Bloomer worked; then again, its placement may have been only a matter of convenience.

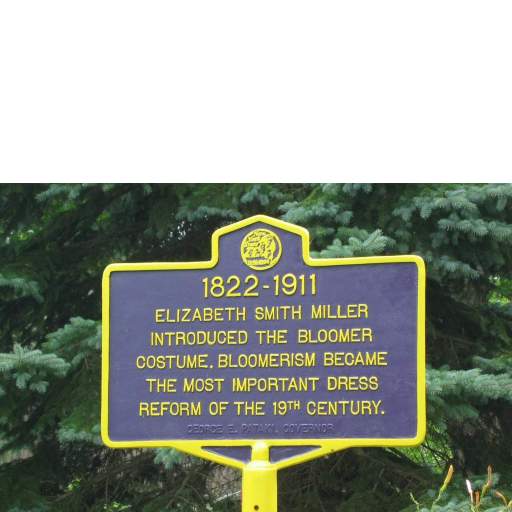

Peterboro Marker

This historical marker in Peterboro, beside the house where Elizabeth Smith Miller resided when she designed the "Bloomer costume," underscores the costume's importance to the causes of woman's rights and dress reform.

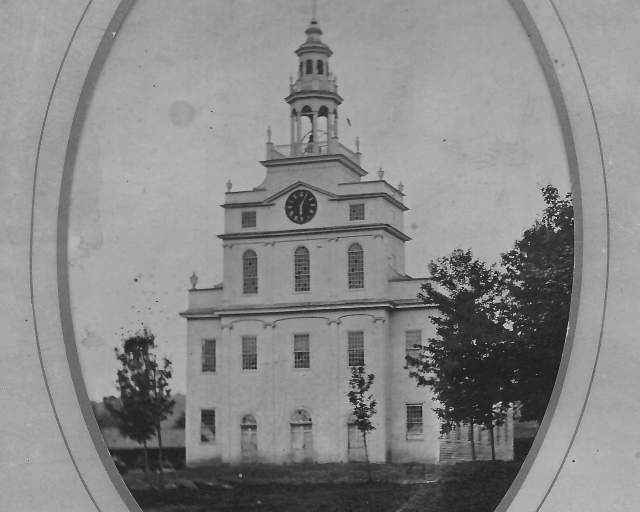

Did Amelia Live Here?

Local tradition holds that this was the Fuller house where Dexter and Amelia Bloomer lived for a few months on their arrival in Seneca Falls. This Italianate-style structure would appear to be the original structure built circa 1930. Later research suggests that another building may have stood here when the Bloomers arrived in April 1840. In any case, in 1980 this structure was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as Amelia Bloomer's residence.

Did Amelia Live Here?—Another View

Again if the National Register of Historic Places account is true, this decidedly less attractive addition was added to the house circa 1850, a decade after the Bloomers moved out. (In this image, the porch of the Italianate main section is visible at left. The main section's upper stories are obscured by the large tree.)

Associated Historical Events

First Annual Meeting of the NDRA

June 18 - 19, 1856