Born in 1818 in Massachusetts, Lucy Newhall embraced the causes of abolitionism and woman’s rights (nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's). By 1852 she renounced Universalism for Spiritualism, in part because she found the Universalists insufficiently zealous about abolitionism. Later she would conclusively embrace freethought. She established a reputation as a campaigner for liberal causes whose special gift lay in silencing Christian hecklers by throwing their own principles back at them.

She married twice, at the ages of eighteen and twenty-six, losing the first husband to consumption and the second, Luther Colman, to an 1852 railroad accident. She spurned a Universalist funeral in favor of a Spiritualist service; she was able to secure the nationally prominent Spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis to officiate.

Colman was then living in Rochester. A widow with a seven-year-old daughter to raise, Colman sought what employment she could obtain. She became a teacher in a segregated "colored school." So deeply did she resent its segregation—and also being paid less than half the amount paid to her male predecessor—that she lobbied parents to withdraw their children, allegedly causing the school to close. (At that time an experiment with integrated public schools was attracting much interest.) She left Rochester soon after, leaving behind close friends including Amy Post and Frederick Douglass.

By the late 1850s, Colman had conclusively rejected Spiritualism, even comparing it to the "outbreak of a disease." When her daughter Gertrude tragically died in 1862, Colman refused traditional observances altogether, opting instead for a secular memorial conducted by Douglass.

Colman was the third person in the room when President Abraham Lincoln had his famous October 29, 1864, White House meeting with antislavery icon Sojourner Truth. (Colman was there to transcribe the proceedings.) Interestingly, Truth and Colman would recall the meeting quite differently: Truth recalling it with great pleasure, while Colman reported frustration with Lincoln when he said he was not an abolitionist and would have passed on freeing the slaves if he could have saved the Union in some other way.

For some years, Colman supported herself (barely) as an itinerant freethought lecturer, speaking mostly in Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois. Then she spent several years working in Washington, D.C., and Richmond, Virginia. By this time she had moved to Syracuse, New York, and was considering retirement. A letter from D. M. Bennett, publisher of the national freethought newspaper The Truth Seeker, persuaded her instead to commit herself to freethought activism. She began to write for The Truth Seeker and another freethought paper, The Boston Investigator. Her column in The Truth Seeker was titled "Reminiscences." She grew very close to the publication and its readers, once writing: "The Truth Seeker family, with its supporters are very dear to me—my own family, as I have no other, I may call it."

Colman attended the 1878 New York State Freethinkers’ Association Convention in Watkins Glen, at which Bennett and two others (W. S. Bell and Josephine Tilton, both of Boston) were arrested for selling a marriage reform and birth control tract. Colman arranged bail for Tilton, who alone remained in the Watkins jail. (Elizabeth Smith Miller had previously offered to pay Tilton’s bail but reneged after she read the tract in question, Cupid’s Yokes by Ezra Heywood.) Colman thereafter campaigned successfully for charges to be dropped against all three.

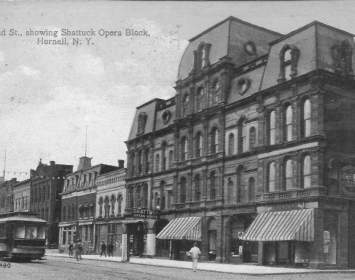

She is also known to have spoken at the New York Freethinkers’ Association fourth convention held at Hornellsville on September 2–6, 1880, as did the celebrated agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll.

Colman was a life member of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association.

Writing in 1901 in the anarchist periodical Lucifer, the Light Bearer, Colman summed up her work in these words: "There is so much for the reformer to do, so many wrongs to be abolished, so much that is wrong in ourselves that we need to overcome or destroy, that I am often disheartened and think I may as well stop doing; but 'tis my nature to try to do, even though the result is so small."

At Syracuse, Colman composed her autobiography. Titled Reminiscences, it drew heavily on her past Truth Seeker columns of the same name. She died in 1906 at age eighty-eight.

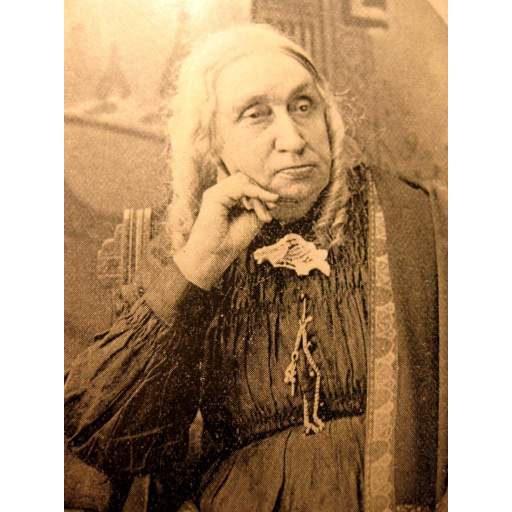

Lucy N. Colman

Lucy N. Colman.

Associated Historical Events

Fourth New York Freethinkers Association Convention

September 2–6, 1880