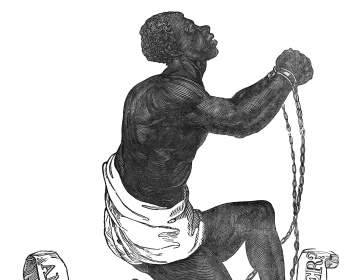

Frances Wright (1795–1852), also known as Fanny Wright, was a freethinker, feminist, abolitionist, and sex radical. She was one of the first women to address audiences of mixed gender across the United States, including in west-central New York State. She was born in Scotland; her father, James Wright, was a wealthy Scottish linen manufacturer whose radical political views included admiration for Thomas Paine. Orphaned at age three, “Fanny” was raised by a maternal aunt living in England. Her education included the philosophy of French materialism. At sixteen, she returned to Scotland, living with a great uncle and traveling extensively.

Wright’s large inheritance allowed her to travel freely. In 1818, the twenty-three-year-old Wright spent two years touring America in the company of a younger sister. Among many other things, on this trip she personally witnessed slavery, intensifying her abolitionist sentiments. She attacked organized religion and capitalism and argued for equal education for both sexes; sexual freedom for women, including birth control; the emancipation of slaves; and free public education in government-run boarding schools for all children beginning at age two. Returning to England in 1820, Wright befriended philosopher Jeremy Bentham and Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. She and General Lafayette enjoyed a close relationship for some years, leaving historians uncertain whether Wright became Lafayette’s lover or something more resembling an adopted daughter. As historian Carol Kolmerten wrote, “Their intimacy, whether that of friends or lovers, helped give her more intellectual confidence as she imagined grand schemes for liberating the world.”

In 1821, Wright published a successful book, Views of Society and Manners in America, a critical travelogue and contemplation of American society which preceded de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America by some fourteen years. (In the same year, Frances Marie Charles Fourier published his seminal Utopian book, A Treatise on Domestic and Agricultural Association, which Wright greatly admired. Fourier’s ideas, though in distorted form, would inspire some three hundred American Utopian colonies, including the freethinking Skaneateles Community and the partly freethinking Sodus Bay Phalanx.)

Views of Society and Manners in America made Wright a celebrity in the United States. In 1824 she returned to America, alternately traveling with or following Lafayette. In February 1825, she heard reformer Robert Owen speak in Washington, D.C., about his then-new intentional “community of equality” in southwestern Indiana. This was the famous, if short-lived, New Harmony community; Wright visited it twice later that year and formed the idea to create her own intentional community where slaves could live, work, and be educated in dignity while they earned the price of their freedom. In October 1825, she announced a community called Nashoba, located at the site of present-day Germantown, Tennessee (near Memphis), founded on principles of racial and gender equality. Like many Utopian communities, Nashoba suffered from (in Kolmerten’s words) “too little money, too little food, and too much to do.” In summer 1826, Wright became ill, perhaps with malaria, and early the next year she sailed to Europe to convalesce. During her absence, a disgruntled white Nashoba resident published an allegation that the community permitted inter-racial cohabitation. This sparked a nation-wide outcry against Nashoba as a “free love colony”—and against Wright, who was unable to offer a timely response.

When Wright returned to America in 1828, Nashoba was closed and her reputation was in tatters. She despaired of leading “the existing generation” to social reform. Instead she turned to journalism and lecturing to spread her ideas. She teamed with Robert Dale Owen, son of Robert Owen, to purchase the New Harmony Gazette, the newspaper of the then-failing New Harmony community. They retitled the paper The Free Enquirer, and Wright began to edit it in New York City. The Free Enquirer became one of America’s first freethought periodicals; the present-day secular humanist magazine Free Inquiry (founded 1980) chose its name as a tribute to Wright’s paper.

During this period Wright traveled widely, speaking on her wide range of reform topics. In so doing she provoked continual outcry, as it was then generally considered unseemly for a woman to address an audience of mixed gender on any subject, much less criticism of religion; calls for abolition, woman’s rights (nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's), and better treatment of the working class; and advocacy of sexual liberty. Many of these lectures took place along the Freethought Trail, but owing to the very early date it has not yet been possible to determine the exact locations at which most of these events were held, precluding their listing on the Trail.

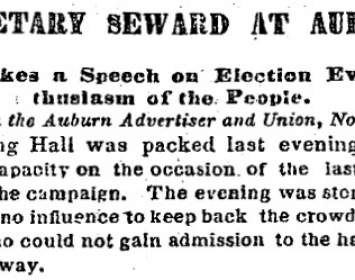

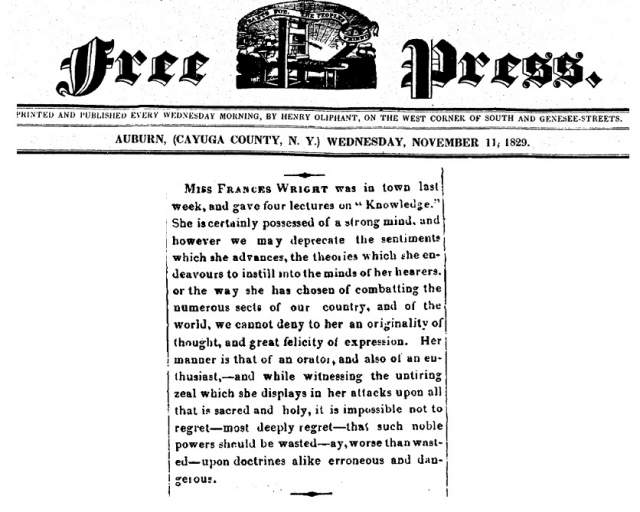

In October 1829, the doubting radical cleric Orestes Brownson heard Wright lecture on abolition at Utica, New York. During the first week of November, Wright delivered her philosophical lecture "On The Nature of Knowledge" in Brownson's home town of Auburn, probably at Corning Hall, after which Wright and Brownson became friends. This led Brownson to his brief period of open unbelief, including a year as a correspondent for The Free Enquirer. Though Brownson would return to his Unitarian roots and eventually become a Roman Catholic intellectual, he and Wright remained friends.

Later in October 1829, Wright and a friend, William Phiquepal, sailed to Haiti with the slaves from Nashoba, whom she planned to free there. Wright and Phiquepal had a daughter and entered into a turbulent marriage that ended in a bitterly contested divorce. Returning to the U.S. in 1835, Wright was unable to regain her former prominence. Alone and renounced by many of her former colleagues (including Robert Dale Owen), Wright died alone in Cincinnati, Ohio, at the age of fifty-seven.

Posthumously Frances Wright earned wide recognition as a pioneer in the fight for woman’s equality, as a role model for women participating in anti-slavery activism, and as an early champion of American freethought. In 1997, her grave marker in Spring Grove Cemetery outside Cincinnati was restored by the Free Inquiry Group, a local secular humanist group associated with Free Inquiry’s publisher, the Council for Secular Humanism; the Freedom from Religion Foundation; and the feminist caucus of the American Humanist Association.

Images of an 1829 book published by The Free Enquirer which reproduces the text of ten of Wright's standard lectures, including "On the Nature of Knowledge," are available here.

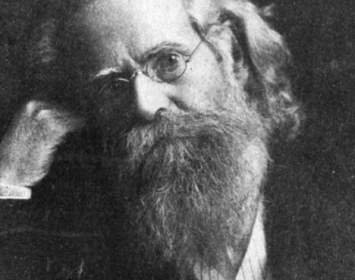

Frances Wright

Frances "Fanny" Wright.