Two noteworthy events were held at Canastota's Dutch Reformed Church (organized 1833), then located on Peterboro Street by the railroad tracks. A regional convention of the the abolitionist Liberty Party was held early in September, 1852. The nation's first significant dress reform convention was held there on January 7–8, 1857.

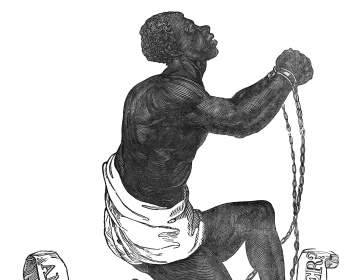

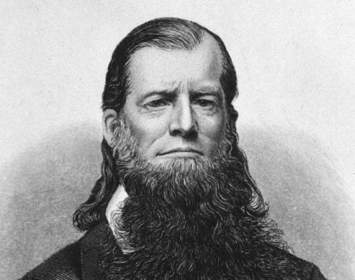

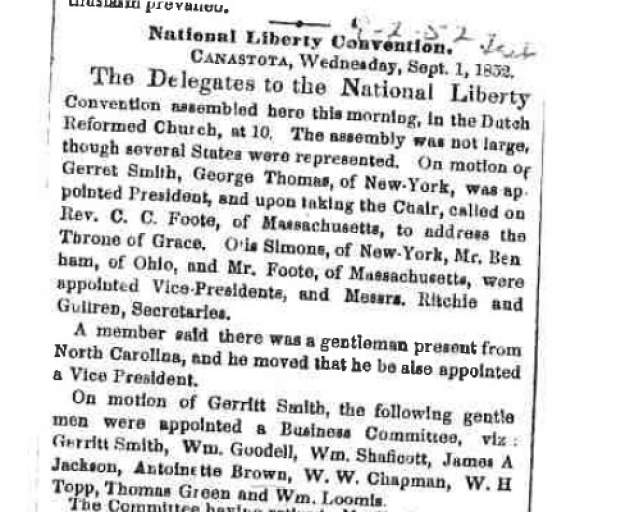

Liberty Party Convention. The 1852 Liberty Party convention attracted delegates from several states. Gerrit Smith of nearby Peterboro attended. Syracuse abolitionist Jermain Loguen was among the vice presidents of the event. Convention business consisted largely of hearing reports of delegates from other states about the climate toward abolition in their areas. Later there was discussion whether the Party should nominate its own candidates for president and vice-president of the United States or support the nominees of “the Free Democracy,” apparently a now-obscure third party that still recognized the legality of slavery. Though Gerrit Smith recommended this step, a majority supported a resolution for the Party not to cooperate with Free Democracy but to nominate its own candidates. A newspaper account of the time suggests that the convention's business was conducted entirely on September 1; other sources maintain that the convention occurred on September 2–3. The reasons for this disagreement are unclear.

Dress Reform Convention. The 1857 convention of the National Dress Reform Association (NDRA) was chaired by its founder, James Caleb Jackson. Speakers included Gerrit Smith and Dr. Mary Edwards Walker of Oswego. A supportive letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read to the convention.

By the time of this convention, most woman's suffrage advocates, including Stanton, had long abandoned reform dress, specifically the Bloomer costume. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) Suffrage leaders, including Stanton, had concluded that it distracted from their mission to win women the vote. (Stanton’s letter may have been written in response to an appeal from her cousin, Gerrit Smith, one of very few activists who had advocated dress reform as an adjunct to suffrage work but continued supporting the cause after suffragists stepped away.) In any case, even when they embraced it, suffragists had never been inclined to support the dress reform cause by holding a convention dedicated to the topic. It was water-cure quacks such as Jackson, who succeeded the suffragists as dress-reform champions, who felt the need to promote the cause by means of conventions. A thumbnail history of dress reform is available here.

Building(s) and Sites(s). The 1833 church site was abandoned in 1878 due to increasing noise from the New York Central Railroad. The church moved two blocks north to a church building at 116 Center Street. That building had previously housed the Free Church, an non-denominational abolitionist congregation.

The historical record is unclear on the relationship between the Free Church and the former Dutch Reformed Church—the latter may have succeeded the former, or they may have used the structure cooperatively. It is known that the Dutch Reformed Church reorganized in 1886 and became the Presbyterian Church Society. In some way, the congregation (or congregations) active at 116 Center Street spun off the present Methodist United Church of Canastota a few doors south. That structure, erected circa 1903 at 144 Center Street, still houses an active congregation.

The church at 116 Center Street faced a harsher fate. By the time the Methodist church was built, it may have housed no congregation. Or perhaps, its sole remaining congregation was the one that built and occupied the Methodist church. The empty old church was repurposed by the Grange, a fraternal organization devoted to agriculture. The Grange abandoned the structure in the 1960s; after decades of housing various restaurants, it was shuttered and acquired by the Village of Canastota. At some point it was sold to a private party who had hopes of restoring the building in some manner. In the mid-2000s it operated for a time as an art gallery. In the intervening years, none of several proposals to rehabilitate the structure has yet borne fruit.

Liberty Party convention clipping courtesy of Sarah Kozma.

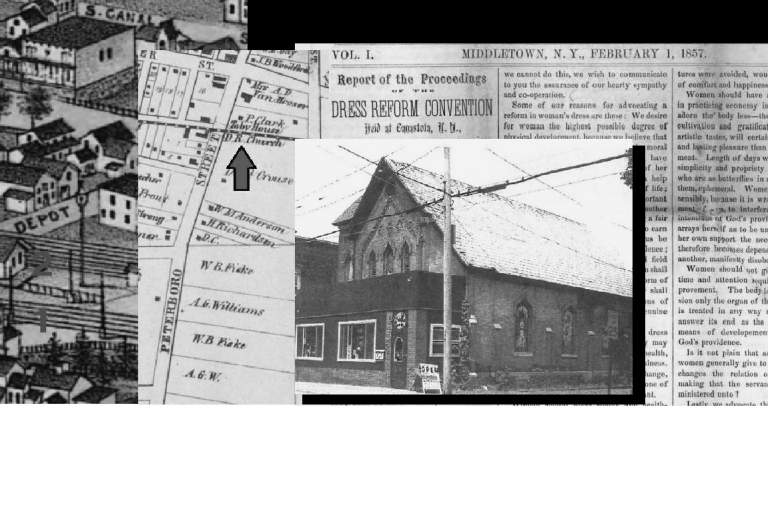

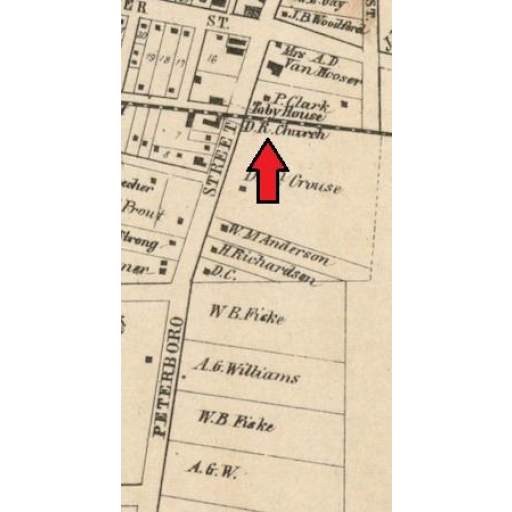

Location of Dutch Reformed Church

This 1857 map of Canastota, New York, shows the location of the Dutch Reformed Church (red arrow). The site is now a small municipal park. Image courtesy Joe DiGiorgio.

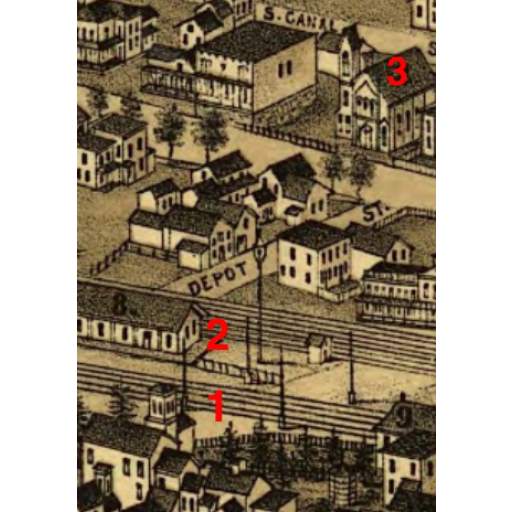

1885 view of Canastota

This 1885 view of Canastota shows the site of the Dutch Reformed Church, abandoned seven years earlier (#1); the railroad depot (#2); and the Presbyterian Church Society (#3). The Dutch Reformed Church abandoned its original church in 1878 and moved to a new location farther from the noisy railroad tracks; in 1886, it reorganized as Presbyterian. Image courtesy Joe DiGiorgio.

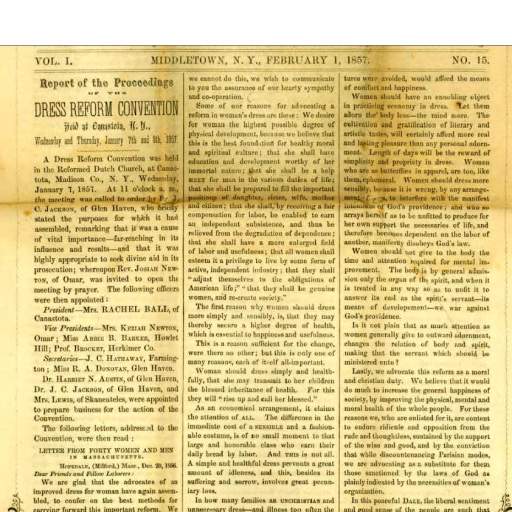

Sibyl Story

The Canastota Convention was covered in the dress reform newspaper The Sibyl. Research assistance by Jim Barri.

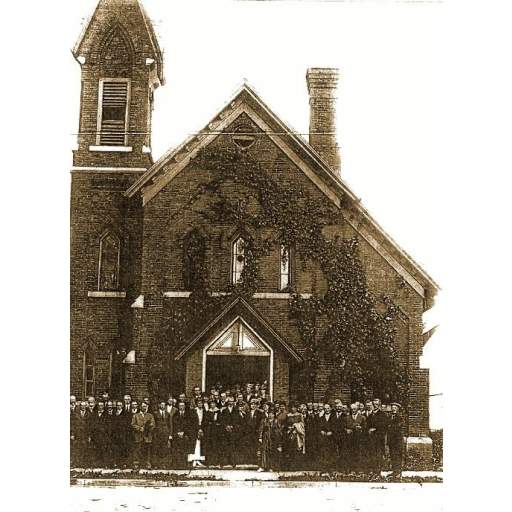

Free Church

The Free Church at 116 Center Street became the new home of the Dutch Reformed Church. This photo shows the church's stone structure, which replaced an original wooden building that burned down in 1871. Image courtesy Joe DiGiorgio.

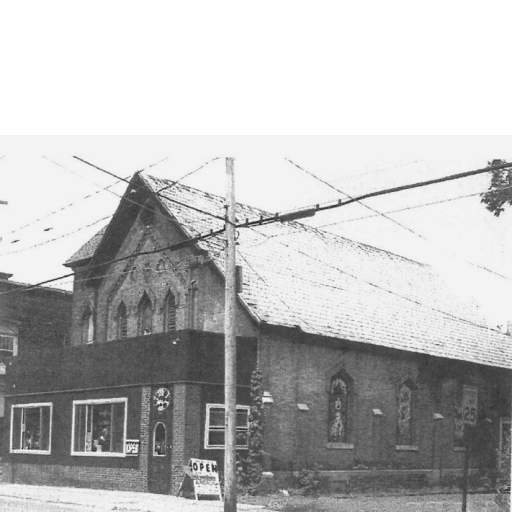

Free Church 2005

The Free Church/Grange building in 2005, when it housed an art gallery. Image courtesy Joe DiGiorgio.

United Church

This quaint red brick church at 144 Center Street appears to have succeeded the church building at 116 Center Street.

1903 Plaque

This plaque affixed to the exterior of today's United Church of Canastota (Methodist) gives its construction date as circa 1903. This is about the same time when the older church at 116 Center ceased to serve any congregation.

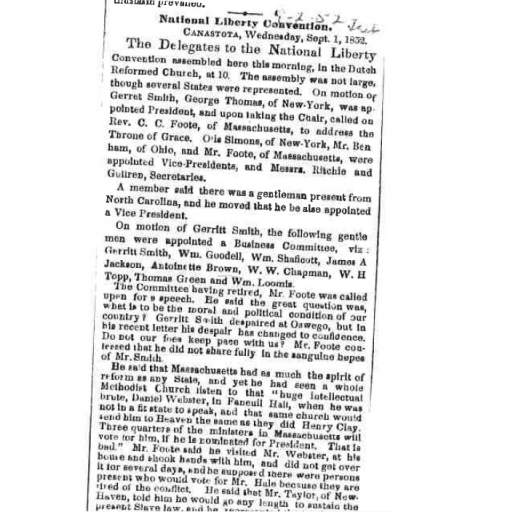

Newspaper Report of LP Convention

This newspaper article reports on the September 2–3 Liberty Party convention at Canastota. Image courtesy Sarah Kozma.

Associated Historical Events

Liberty Party Convention at Canastota

September 1852

First National Dress Reform Association Convention

January 7–8, 1857