The Sodus Bay Phalanx was an ostensibly Fourierist Utopian intentional community. Of the roughly three hundred Fourierist communes that sprang up across America in the 1840s, it was the only one whose population was approximately evenly divided between Christians and freethinkers. The communal experiment lasted just two years—slightly below the norm for Fourierist communes of that period.

Fourierism advocated for communities organized into “phalanxes” freed from private ownership in order to provide economic comfort, social justice, and individual fulfillment. “Phalanx” was the English term for a Fourierist community, transliterated from the French phalanstère, a coinage by eccentric French thinker Charles Fourier that combined the French words phalange (phalanx, a basic ancient Greek military formation) and monastère (monastery).

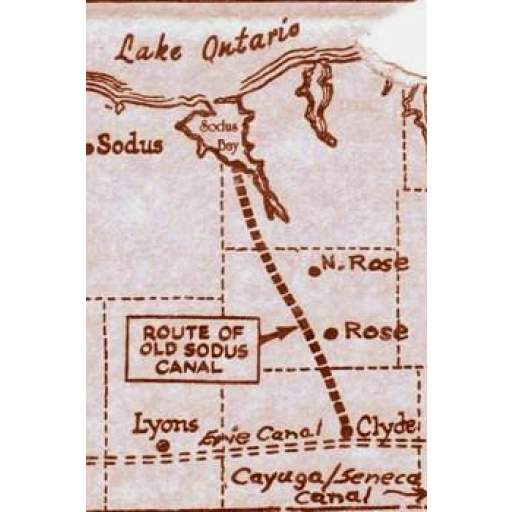

Complex Beginnings. The Sodus Bay Phalanx’s beginnings were complex in many ways, only one of which was fortuitous: its site. In February 1826, the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, better known as the Shakers, bought 1,400 acres on the shore of Sodus Bay. (Sodus Bay is on the south shore of Lake Ontario, midway between Rochester and Syracuse.) There the Shakers built an intentional community comprising orchards, crop lands, and some seventeen buildings. Four large extended families occupied the site, about 150 persons in all. The community prospered, selling seeds, fruit trees, vegetables, salted fish, flax, and household products such as brooms. A grist mill, saw mill, and blacksmith shop were also busy. Inspired by the great success of the Erie Canal, local promoters proposed a canal connecting Sodus Point to the Erie Canal at Clyde. If built, the canal would have bisected the Shaker commune. In 1838, the Shakers sold their tract of land to canal promoters and built a new community in Groveland, New York, near Sonyea. Very shortly thereafter, the canal project failed, a delayed casualty of the Panic of 1837—and an empty, fully developed site ideally suitable for some other mid-sized commune went on the market.

The other complexity concerns the founding of the Phalanx itself. That story began on August 22, 1843, when the Fourier Society of the City of Rochester held its first convention at Monroe Hall. This event had been promoted by Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, and convened by Albert Brisbane of New York City, the American Fourierist who had sparked Greeley’s interest in the movement. That convention sparked the formation of Utopian communes as far west as Illinois. The Rochester Society’s president was the prominent Hicksite Quaker abolitionist Benjamin Fish. At this convention was organized the Ontario Phalanx, an entity inspired by the North American Phalanx in New Jersey. Its goal was to form one large Fourierist community for all of west-central New York. That was the strategy Brisbane had recommended, exhorting those assembled to avoid “small and fragmental undertakings.” Six weeks later, on October 14, that strategy was shattered when the picaresque promoter John Anderson Collins launched a small local Fourierist community at Skaneateles. (Members of that community were almost entirely freethinkers.) Five weeks after that, on November 21, 1843, the Fourier Society of Rochester met again at the Athenaeum, an important downtown meeting hall. Forsaking regionalism, it rashly urged any group interested in launching a Fourierist community, however narrow its focus, to push ahead and do so. For its part, the Ontario Phalanx resolved to establish a more limited community, but its leaders could not agree on a site. The Ontario Phalanx split in two. The larger faction favored a location in Clarkson, northwest of Rochester. A rump group led by Benjamin Fish preferred the “Shaker Tract” on Sodus Bay because it was so well-appointed. This split slowed recruitment for both proposed communes and caused the Fourier Society of Rochester to dissolve.

The Community Opens, and Immediately Fragments. In January 1844, Benjamin Fish and his faction purchased the Shaker Tract. Those members already recruited moved in at once. This group was roughly equally divided between freethinkers, most of whom were vegetarians, and moderately liberal Christians, most of whom ate meat. Conflict erupted immediately over food preferences and more substantive issues, such as whether labor should be permitted on Sundays. In addition, large numbers of unskilled or just unproductive "members" thronged the community, drawn by its unsustainable promise of a year’s free room and board. Nonetheless, Fish and his compatriots pressed on.

Around this time, the supporters of the alternative commune site at Clarkson split yet again. Small phalanxes were established at both Clarkson and North Bloomfield, New York. Each would be short-lived.

On January 23, 1844, the Sodus Bay Phalanx published a prospectus and constitution in the Rochester Republican newspaper, seeking additional members. The document listed Benjamin Fish as a leader of the commune and named nonresident members, including the Rochester abolitionists Isaac and Amy Post and Huldah Anthony—a cousin of Susan B. Anthony—and her husband, Asa. By March the Sodus Bay Phalanx boasted about 300 members, many of them women and children. In their numbers and skills, the available able-bodied men were insufficient to operate the community to its full potential.

In June 1844, Dexter C. Bloomer, husband of woman’s rights and dress reform activist Amelia Bloomer, visited the Sodus Bay Phalanx and commented on its startling religious diversity. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.)

Religious Dissension. Religious dissension was tearing the community apart. Soon ten members were abandoning the Phalanx each month. In August, a devout Phalanx member brought a formal complaint against two freethinking members because they had worked in a field on the Sabbath. The case was so sensitive that it was weighed by the Phalanx’s entire board of directors, which voted four-three to acquit the freethinkers. In September, conflict spiked. Ten members gave notice of intent to leave in a single two-week period. By month’s end, the more religious members of the community had largely abandoned it, taking with them what of their property they could and a bit more besides, leaving the remaining freethinkers bereft of essential resources.

In October 1844, the declining Phalanx adopted a new constitution. Oddly, it was the first in the community’s history to mention the essential Fourierist principle of series. The new constitution did nothing to arrest the Phalanx’s decline. On December 9, 1844, a national Fourierist newspaper, The Phalanx, conceded that the Sodus Bay Phalanx was failing, “a striking example of the folly of undertaking practical Association without sufficient means, and without men of proper character.” On April 7, 1845, the Sodus Bay community adopted yet another new constitution and renamed itself the Sodus Phalanx. In September, correspondent Lorenzo Marrett reported in The Harbinger, another Fourierist paper, that the Sodus community still functioned, albeit with only “twelve to fifteen adult males” and no prospect of paying its remaining debts.

Dissolution and Disposal. On April 4, 1846, dissolution of the Sodus Phalanx was announced. Loyal to the end, Benjamin Fish served on a committee to conclude the community’s remaining business. By April 17 that committee had completed its work, distributing the Phalanx’s residual assets. The Shaker Tract reverted to the canal company, whose promoters were still struggling to revive that project. The Clyde to Sodus Canal was never built.

Sometime after 1856, about 1,300 acres of the original tract were auctioned off. Today the former Shaker Tract is now in the hamlet of Alton. In 1924 it was reorganized as Alasa Farms, an experimental argicultural facility. In 2011 the property was acquired by the Cracker Box Palace, an animal refuge.

Of the seventeen original buildings, only two frame houses still stand. A February 2009 fire seriously damaged the third-floor interior and one of the second-floor bedrooms. Meanwhile, some buildings of the second Shaker commune, at Groveland, were incorporated into the medium-security Groveland Correctional Facility.

Sodus Bay Phalanx Site

The Sodus Bay Phalanx site is now home to a regionally prominent farm animal sanctuary.

1840s barn

This board-and-batten barn is believed to date from the 1840s. Whether it was erected by the Phalanx or by canal interests after the Phalanx collapsed in 1846 is unknown.

Sodus Canal Route

Proposed route of the Clyde to Sodus Canal, which was never built. Shakers who built the community at Sodus Bay sold the tract to canal developers; when the canal failed, the "Shaker Tract" was available for purchase by Phalanx organizers.

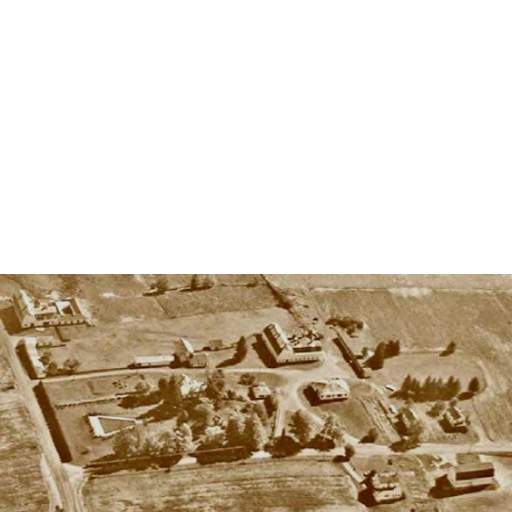

Alasa Farms

Aerial view of Alasa Farms on the site of the Shaker Tract and the Sodus Bay Phalanx.

Animal pen

The site now houses Cracker Box Palace, a refuge for abandoned or abused farm animals.

Associated Historical Events

Rise and Fall of Sodus Bay Phalanx

1843–1846