The Women’s Rights National Historical Park, operated by the National Park Service, celebrates the achievements made in the battle for woman’s rights. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, to refer to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) Its three principal components are the Elizabeth Cady Stanton House, the restored Wesleyan Chapel in downtown Seneca Falls, and (adjacent to the Chapel) the Woman’s Rights Museum.

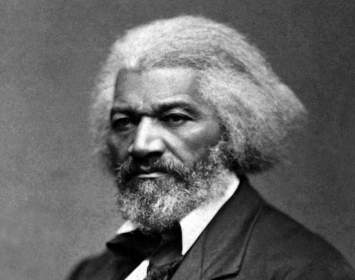

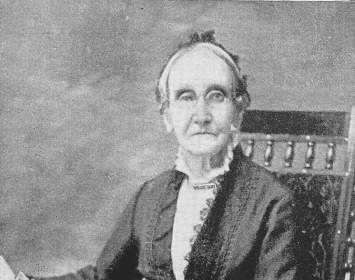

The Wesleyan Chapel served as the site for the first Woman’s Rights Convention on July 19–20,1848, organized by (among others) Elizabeth Cady Stanton and attended by abolition activist Frederick Douglass. This convention sparked the development of first-wave feminism and the nineteenth-century woman’s rights movement, which achieved the vote for women in 1920.

Some three hundred women and forty men attended the 1848 Woman's Rights Convention. The 1848 Convention is best known for adopting the Declaration of Sentiments, a statement of woman’s equality consciously patterned on the Declaration of Independence and signed by about 100 attendees. The Convention also adopted twelve resolutions, of which the most controversial was a then-unprecedented call for "the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise"—that is, the vote.

It is no coincidence that the Convention took place at the then-new Wesleyan Chapel. In 1843, the Wesleyan Methodist Church split from the Methodist Episcopal Church. Issues included whether to oppose slavery abstractly (a sort of bare bones abolitionism) or to engage in more radical forms of activism such as defying the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, sheltering escaped slaves, and participating in the Underground Railroad. The Wesleyans took the more radical position.

Their number included many reformers, including some who believed in equality between men and women. At that time, Seneca Falls was a particular hotbed of radical reform agitation. Seneca Falls’s Wesleyan congregation was the first to build a chapel, and for many years the Seneca Falls chapel was the largest Wesleyan chapel in New York. It was routinely made available for reform speakers and events. No facility then in Seneca Falls would have been more likely to welcome the Woman’s Rights Convention.

For more information, see the Women’s Rights National Historical Park’s official site.

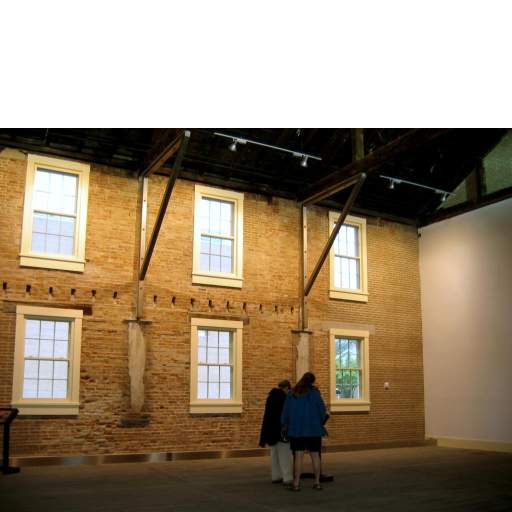

The museum at the Woman's Rights National Historical Park. The fountain wall bearing the text of the Declaration of Sentiments abuts its east wall, at right in this picture. The Wesleyan Chapel lies one door further east, off the right side of this picture.

From the opening of the Woman's Rights National Historical Park until 2011, the remaining original walls of the Wesleyan Chapel were preserved in this open manner. The metal roof replicated the profile of the Chapel's original roof line, long lost. To enhance the interpretive experience, protect interior surfaces from the elements, and create an interior free from traffic noise, the full Chapel was reconstructed in 2011.

The stone wall pictured here is inscribed with the full text of the Declaration of Sentiments adopted at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. This monument abuts the Women's Rights National Historical Park museum (brick wall at upper left) and faces the Wesleyan Chapel site (off photo to right). During the summer, the inscribed wall is washed by a perpetual fountain.

The Wesleyan Chapel was reconstructed in 2011, yielding a significantly improved interpretive experience. New construction is different in color so that remaining original materials may be clearly recognized.

Interior of the reconstructed Wesleyan Chapel, looking southwest. The double doors at right open on to Fall Street.

Architectural details include gaps in brickwork to support joists of the absent second floor, over-window lintel, and surviving fragment of original wall surface (under plexiglass at right).

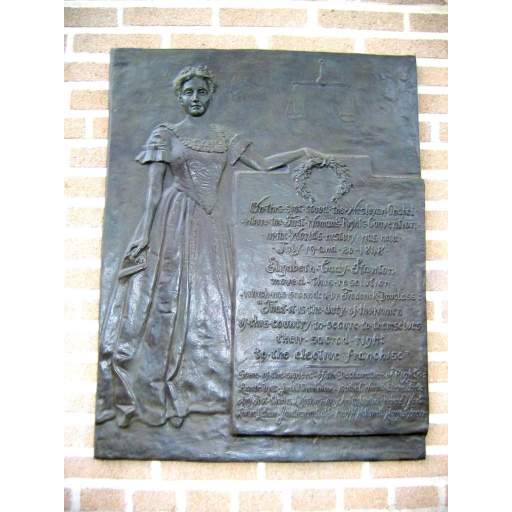

This mid-twentieth century plaque commemorates Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the first Woman's Rights Conference held on this site. It was attached to the remains of the Wesleyan Chapel decades before any of the current restoration work began.

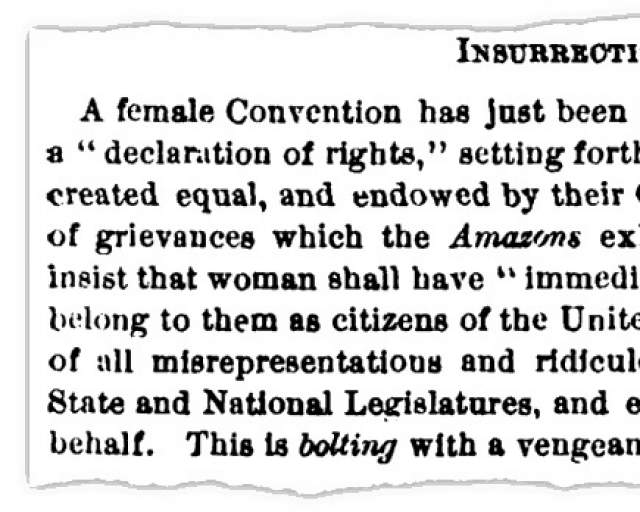

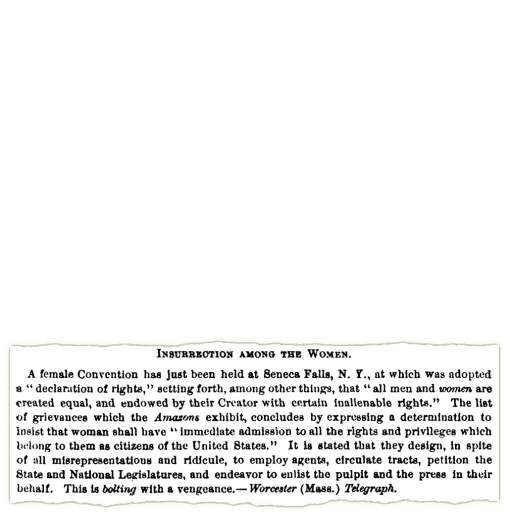

Hostile press comment on Convention

Aside from Frederick Douglass's antislavery paper The North Star, few newspapers gave the Seneca Falls convention favorable notice. Most published commentaries were rude, dismissive, or outright insulting. This comment by a Massachusetts paper was typical; Elizabeth Cady Stanton reproduced it in her autobiography Eighty Years and More.

Associated Causes

Associated Historical Events

Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls

July 19–20, 1848