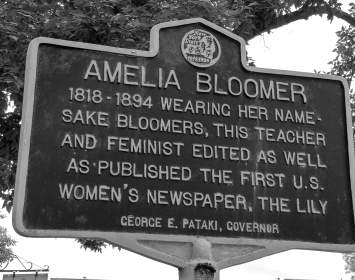

A peak period in reform-dress activism occurred among woman’s rights and suffrage activists in west-central New York State. Early in 1851, Elizabeth Smith Miller of Peterboro, the daughter of abolitionist philanthropist Gerrit Smith, designed the definitive "reform dress" style: a roughly knee-length skirt worn over Turkish-style pantaloons. Accounts suggest that Miller wore the reform style while visiting Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Seneca Falls; Stanton immediately copied the garment. (At this time middle-class women made most of their own clothing, often without the benefit of patterns; a new style could spread rapidly by simple imitation.) In short order, Amelia Jenks Bloomer, also of Seneca Falls, made her own reform costume. Bloomer, considering the new style superior to traditional women’s fashions, began to promote Miller’s version of reform dress in the temperance and woman’s rights paper she edited, The Lily.

Later in spring 1851, Miller, Stanton, and Bloomer stepped out onto the streets of Seneca Falls, each wearing a comparatively short skirt over pantaloons, which they called "freedom dress." This was a masterwork of guerrilla theater; not only did their promenade cause a local sensation, it earned reportage in newspapers across the nation. Reporters competed to coin their own witty names for the new style. What stuck was "Bloomers," a nod toward Amelia Bloomer. To this day, Amelia Bloomer is often misidentified as the inventor of a reform fashion she did not invent but rather did the most to publicize.

Stanton, Bloomer, Miller, and others built organizations to campaign for woman’s rights. But Stanton thought dress reform required no such formal organization. She expected that the example set by prominent women adopting reform apparel would prompt countless others to adopt the style on their own. While matters didn’t work out that way, Stanton was successful in persuading woman’s rights campaigners Lucy Stone and Sarah and Angelina Grimké to take up the costume. One of Stanton’s final conquests was Susan B. Anthony, who bobbed her hair and donned Bloomers for a December 1852 lecture in Auburn.

Reform dress for women touched a nerve, sparking anger and ridicule. Newspaper cartoons sneered that if women took on masculine characteristics by wearing pantaloons, men would don dresses and become dependent and "feminized." Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, otherwise a strong supporter of the women’s movement, stridently urged abandonment of reform dress. Indeed, among male supporters of women’s rights, only Gerrit Smith supported pantaloons reform dress. Traditional women’s garb, he complained, "both marks and makes their impotence." So intense was Smith's support that it seemed he thought pantaloons alone would make women equal.

It soon became apparent to woman’s rights advocates that the Bloomer costume was a distraction; critics would focus on their apparel rather than hearing them out on topics such as suffrage. By the end of 1853, Stanton abandoned the Bloomer costume. She soon persuaded Lucy Stone to do likewise. Anthony, who had been slow to take up Bloomers, was also slow to discard them, continuing to wear the style until mid-1854. As for Amelia Bloomer, she continued to wear short skirts over pantaloons until 1858, when she gave it up for a new fashion, the light-weight wire hoop skirt. (By that time, she had moved with her husband to Council Bluffs, Iowa.) The last suffragist to forsake the Bloomer costume was Elizabeth Smith Miller, who continued wearing it, in part to please her father, until as late as 1861.

Bloomer Costume

Period illustration of a Bloomer Costume, with a (relatively) short skirt over pantaloons. The engraving may depict Elizabeth Smith Miller.