The idea of reform dress (more practical garments for women, notably a relatively short dress over pantaloons) arose repeatedly during the nineteenth century, first at the Owenite Utopian community in New Harmony, Indiana. In the 1850s the so-called Bloomer costume was taken up by suffrage leaders, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Amelia Jenks Bloomer (for whom the style was named), Elizabeth Smith Miller (who actually designed the costume), Lucy Stone, and Sarah and Angelina Grimké—only to be abandoned by most of them later in the decade out of concern that sensationalism over suffragists' mode of dress was obscuring their message. What never happened during these years was the rise of any discrete organization to promote reform dress. Stanton, in particular, was adamant that no such organization was needed.

That changed when a new group took up the mantle of reform dress: practitioners of hydropathy (water cure), a then-popular quack therapy that involved mineral-water baths, steam baths, and pure foods, often administered in a residential sanitarium setting. In February 1856, abolitionist and Town of Sempronius hydropathist James Caleb Jackson founded the National Dress Reform Association (NDRA).

An abolitionist and health reformer who also invented Granula, the first dry whole grain breakfast cereal, Jackson claimed, controversially, to have invented pantaloons reform dress in 1849—two years before Elizabeth Smith Miller created the Bloomer costume—as a garment for patients at his spa. (Despite his implicitly challenging Miller's claim to have invented the Bloomer costume, Jackson maintained a close relationship with her father, Gerrit Smith; the two knew each other well from abolition activism in the Liberty Party in the 1840s.)

With the NDRA, dress reform now enjoyed the institutional infrastructure that suffragists hadn’t thought it needed. The NDRA redubbed the Bloomer "the American Costume," touting its health benefits. The organization was generally cool toward suffrage, arguing that a revolution in women’s apparel, not the vote, was what was most needed to make women free.

Also in 1856 was founded The Sibyl: A Review of the Tastes, Errors and Fashions of Society, an independent newspaper edited by another hydropathist, Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck, which campaigned in support of NDRA’s cause.

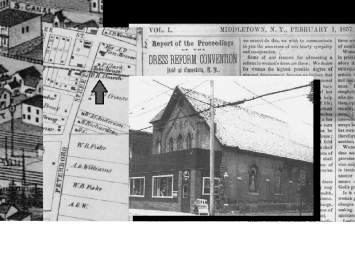

The NDRA held its first national convention at the Dutch Reformed Church in Canastota on January 7–8, 1857. The choice of Canastota, but seven miles north of Gerrit Smith’s home in Peterboro, presumably reflected Smith’s support for the event. Jackson presided; Smith attended and participated enthusiastically. Oswego radical dress-reformer Mary Edwards Walker also spoke. A letter of support from Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read to the delegates.

In 1860, Walker would be elected Third Vice President at the National Dress Reform Association’s fourth annual meeting in Waterloo. At the same organization’s 1863 conference in Rochester, she was elected Sixth Vice President, though she was already off at war.

The NDRA convened each year until 1861 and intermittently during the Civil War. (The Sibyl ceased publication in 1864.)

Fall of the NDRA. The NDRA collapsed at its final convention, held June 21, 1865, at Rochester's Corinthian Hall. There Jackson and Hasbrouck, then the group’s president, had a bitter public spat over who was in charge of the proceedings.

The cause of pantaloons dress reform would next be taken up by the Seventh Day Adventist church. The Adventist enthusiasm for reform dress ended during the late 1870s. In the 1890s, traditional dress reform activism was rendered moot by the craze for bicycling, which generated independent demand for more practical fashions among woman cyclists.

Associated Causes

Associated Historical Events

First National Dress Reform Association Convention

January 7–8, 1857

Final National Dress Reform Association Convention

June 21, 1865