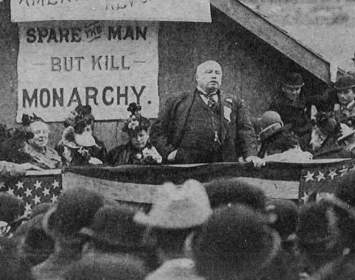

The New York Freethinkers Association played a significant role in the Golden Age of Freethought, which lasted from the end of the American Civil War to about the turn of the twentieth century. Despite its name, the New York Freethinkers Association was an organization of national scope, and its periodic conventions attracted many of the most prominent figures in freethought and related reform movements. Among them were C. D. B. Mills, the Syracuse abolitionist who long served as an officer of the association; Robert Green Ingersoll, the nation’s most famous freethought orator; D. M. Bennett, publisher of The Truth Seeker, the nation’s largest-circulation freethought newspaper; reformer-activist Matilda Joslyn Gage; and many others.

Embracing Diverse Subgroups. The Association appealed to a wide range of religious dissenters, from Materialists—who rejected any role for "spirit" and sought to live without religion—to advocates of a new Religion of Humanity free of supernaturalism to enthusiasts of Buddhism and other Eastern traditions. Also involved were a number of Shakers and a substantial number of Spiritualists, both religious minorities that rejected much of Christian orthodoxy. The Spiritualists saw themselves as forming the "heart" of freethought, in comparison to Materialists and other scientific hardliners whom they viewed as forming its "head." In Spiritualist mediums' alleged communication with the dead they claimed evidence that there is a next world and a life after death—just one that bears little resemblance to the afterlife preached by Christianity.

It should be remembered that Spiritualism was then a young movement. Spiritualistic phenomena had not yet undergone rigorous scientific examination at scale. Moreover, in those early days even prominent scientists seriously entertained the notion that Spiritualist claims might be correct. In this connection the remarks of activist, attorney, and scholar Thaddeus Burr Wakefield—an officer of another national freethought organization, the National Liberal League—are most interesting. Speaking at the Association's 1878 convention at Watkins (see below), Wakeman offered this prescient criterion for how Freethought should manage its relations with Spiritualism: "The objection of the scientists must be heeded; that all human errors are, at bottom, mistakes or illusions of the senses woven into facts by the wish of the heart; that only the best skilled scientific experts are competent to unravel and to judge decisively of such facts; that if it appear after such examination that the alleged 'spiritual phenomena' are illusions or are explainable under the laws and relations of our known world, then, without fear, or favor, or hope, any belief to the contrary must be laid aside as a 'Superstition' by all Liberals and lovers of truth."

Of course, that is what happened. As continuing inquiry revealed that Spiritualism's claims were untrue, a process that was largely complete by the 1930s, freethought abandoned it. Today freethought and its companions and successors, atheism and secular humanism, number among the most consistent opponents and debunkers of Spiritualism, which is itself a mere remnant of its former size and vigor.

Conventions of 1877 and 1878. The Association, then known as the Liberals and Freethinkers of Central and Western New York, held its first convention, or “Grove Meeting,” on August 17–19, 1877, at the farm of freethinker James Madison Cosad in Huron, New York. (Some sources give the place name as Wolcott.)

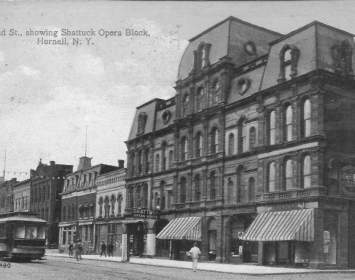

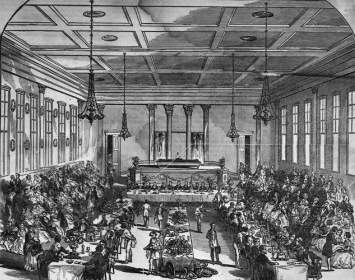

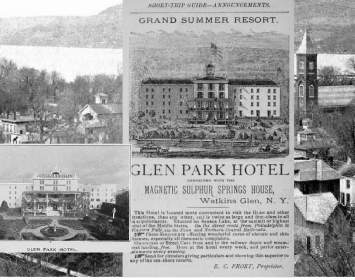

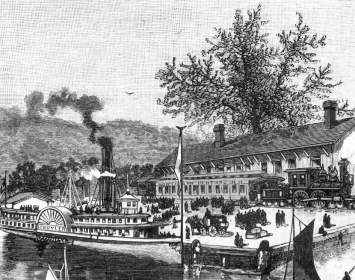

The Association’s second convention, held at Watkins (now Watkins Glen; pictured above) on August 22–25, 1878, was of national import. Participants’ accounts record that villagers gave a frosty reception to this group of largely big-city freethinkers. Plenary sessions took place in a local park and, when conditions were rainy, in a downtown opera house.

The event is especially noteworthy because it was the site of the first freethought lecture by Matilda Joslyn Gage and because it was at this convention that Truth Seeker publisher D. M. Bennett was arrested for selling a banned marriage reform text, Cupid’s Yokes, by anarchist and freelove advocate Ezra Heywood.

At the convention, freelove activist Josephine Tilton left her radical book stand for a short time and asked Bennett to tend it in her stead. While she was gone, someone purchased Cupid’s Yokes from Bennett. The elderly publisher, Boston freethinker W. S. Bell, and later Tilton, were arrested and charged with selling obscene matter. Abolitionist, woman’s rights activist, Quaker, and Spiritualist Amy Post, who attended the Convention, came forward and paid bail for Bennett and Bell. Tilton was later bailed out by feminist activist Elizabeth Smith Miller; later that evening, after reading Cupid’s Yokes, Miller reneged on her payment and Tilton returned to jail. After several days during which Tilton remained in jail as a form of protest, determined to burden the village of Watkins with the price of her board, abolitionist and woman’s rights activist Lucy Colman persuaded Tilton to let Colman bail her out.

While the prosecution based on this incident fizzled out, a bitter feud erupted between Bennett and Anthony Comstock, then the official decency czar of the U.S. Post Office. Eventually Comstock orchestrated Bennett’s arrest for selling Cupid’s Yokes by mail. After a sensational trial, Bennett was sentenced to serve thirteen months of hard labor and to pay a $300 fine. Bennett’s prosecution was widely unpopular; his conviction was criticized in freethought publications but also in the mainstream press. A petition urging President Rutherford B. Hayes to pardon Bennett garnered more than 200,000 signatures, the largest number on a single petition to that date. Despite this petition and a letter from Robert G. Ingersoll encouraging the pardon, Hayes declined—owing in part to the influence of his devout wife, who was in turn influenced by Anthony Comstock and fellow decency campaigner (and soap magnate) Samuel Colgate. Bennett was forced to serve his full sentence.

Because of the controversy attending Bennett's prosecution, his Truth Seeker Company published a complete transcript of the proceedings of the 1878 Watkins convention. As a result, this convention is the only freethought gathering of the period whose full proceedings are a matter of public record.

Conventions after 1878. The Association held its next meetings at Chautauqua Lake (1879) and Hornellsville (1880, 1881).

After his release from prison, D. M. Bennett traveled the world, a tour funded by grateful supporters. The New York Freethinkers Association convened again at Watkins on August 23–27, 1882, this time receiving a more hospitable local reception. Because of inclement weather, all proceedings were held indoors at the Opera House, except for a banquet honoring Bennett, which was held at the Glen Park Hotel. Among those again in attendance was Amy Post. Speakers included Matilda Joslyn Gage and Bennett, who addressed the convention and enjoyed a hero’s welcome upon his return to the village we now know as Watkins Glen.

The 1882 convention had one other historically intriguing consequence. Apparently the convention passed a resolution predicting the gradual extinction of Christianity in America. The Rev. Charles Cardwell McCabe, a leader in new church development for the Methodist church, read of the resolution in a newspaper and cabled the convention with the following message: "All hail the power of Jesus’ name. We are building more than one Methodist church for every day in the year, and propose to make it two a day." Convention president Thaddeus Burr Wakeman cabled back, in part: "Build fewer churches and pay your taxes on them like honest men. Build better churches, since liberty, science, and humanity will need them one of these days and will not wish to pay too much for repairs." McCabe gained wide publicity from this exchange. He became known as "Two-a-Day McCabe"; his cable even inspired a popular evangelical camp song. By the time of McCabe’s death in 1906, it was widely believed he had directed his famous 1882 cable to the celebrated agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll. Ingersoll had been invited to speak at the convention, a fact that organizers promoted quite vigorously. But the "Great Agnostic" was unable to accept. In late August 1882, Ingersoll was fully engaged in conducting what would become the lengthiest criminal defense in U.S. history to that time in the Star Route Trials. Since Ingersoll did not attend the Watkins convention, he played no role in composing either the resolution that provoked McCabe’s message or the convention’s reply.

In subsequent years, the Association convened at Rochester (at Corinthian Hall, 1883), Cassadaga (1884), and Albany (1885).

Watkins Glen, site of 1878 convention

Period view of Watkins (now Watkins Glen), site of the 1878 convention.

Associated Causes

Associated Historical Events

Second New York Freethinkers' Association Convention

August 22–25, 1878

Fourth New York Freethinkers Association Convention

September 2–6, 1880

Fifth New York Freethinkers Association Convention

August 31–September 4, 1881

Sixth New York Freethinkers' Association Convention

August 23–27, 1882

Seventh New York Freethinkers Association Convention

August 29, 1883