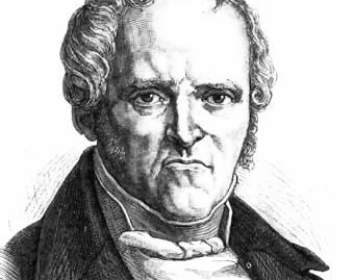

Benjamin Fish (1797–1882) was a Hicksite Quaker, extremely active in the abolition movement. In addition, he would be one of the earliest promoters of a short-lived Fourierist Utopian community, the Sodus Bay Phalanx, and one of the last to abandon the venture when it failed roughly two years later. (Pictured, a barn on the Phalanx site, now a farm and animal shelter; the structure may date to the Phalanx period.)

Fish was born in Rhode Island. He earned his living as a nurseryman. In 1817, the Fish family—Benjamin, his wife, Sarah, and children, including Catherine and Mary—moved to west-central New York State, settling in Farmington, where an active Quaker meetinghouse was situated. When the Orthodox and Hicksite Quakers split in 1828, primarily over the issue of how actively slavery ought to be opposed, the Fishes joined the Hicksites—the more zealously abolitionist sect—and moved to Rochester.

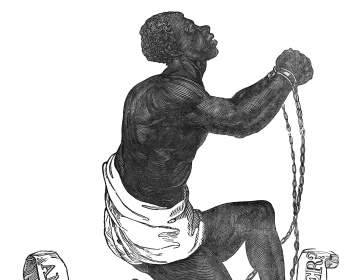

The Fishes were founding members and officers of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society (organized in 1842), whose other members included Frederick Douglass, Isaac and Amy Post, and Asa and Huldah Anthony, cousins of Susan B. Anthony. Fish family members helped organize everything from abolitionist conventions to antislavery craft fairs and were also active in the Underground Railroad. In his autobiography Life and Times, Douglass praised Benjamin Fish and Asa Anthony as "good and true men of Rochester" who "cheered on and supported" his work.

Fish was involved with the Sodus Bay Phalanx from its beginning—which was a complicated affair. By summer 1843, he was president of the Fourier Society of the City of Rochester, which held its first convention August 22–23 at Monroe Hall, a downtown meeting space. At this convention, Fish was also elected president of the Ontario Phalanx, envisaged as a single large Fourierist community serving the entire region. That dream was soon dashed when John Anderson Collins formed a small nearby commune at Skaneateles in October 1843. On November 21, the Fourier Society of the City of Rochester met at the Athenaeum. Abandoning the notion of regionalism, it urged local Fourierist societies to form smaller communes as desired. Even so, the Ontario Phalanx leadership could not agree on where to launch its own local community. In December 1843, the Fourierist Society of the City of Rochester dissolved over this controversy.

In January 1844, Fish led what was effectively a rump group of Ontario Phalanx leadership in signing a prospectus for a new commune, the Sodus Bay Phalanx. The prospectus was published in the Rochester Republican on January 23, 1844. The Utopian community purchased a 1,400-acre tract that had already been developed with communal living and work in mind. The site previously hosted a successful Shaker community that moved away only because a new canal was projected to run through it. The canal venture failed, and the Fourierists were able to purchase a nearly “move-in ready” commune from the canal promoters’ successors. But the price was steep ($35,000).

The under-capitalized Phalanx attracted many members at first, but they did not have the proper mix of skills to make the orchards, grist mill, saw mill, and craft shops productive. Add to that the fact that Fourier’s social and economic principles were unrealistic—not that the Sodus Bay Phalangists (as members of a Phalanx were called) had followed them closely—and that its membership was about evenly divided between devout, if liberal, Christians and freethinkers. Christians and freethinkers quickly clashed over whether work on the Sabbath should be permitted and even over food choice; most of the Christians were meat-eaters while almost all of the freethinkers were vegetarians.

The Sodus Bay Phalanx lasted only two years, formally dissolving on April 4, 1846. Loyal to the end, Fish served on a committee that concluded the Phalanx’s remaining business. He stepped down on April 17, after division of the remaining assets had been completed. Even so, Fish's daughter Catherine married fellow reformer Giles Badger Stebbins at the Phalanx on August 17, 1846.

The Fishes moved briefly back to Rochester, where Fish, his daughter Catherine, and her husband all fell under the spell of the fraudulent Fox Sisters, taken in by their acts of apparent “mediumship,”which actually relied on the young women's ability to pop their toe joints against the floor, producing supposed "spirit rappings." The Fish and Stebbins families were among the Sisters' earliest adherents. Soon the Fox Sisters' fame spread worldwide and launched the Spiritualist movement.

On August 2, 1848, Sarah D. Fish delivered an address to the Rochester Woman's Rights Convention at the city's Unitarian Church. (Sarah's daughter Catherine Fish Stebbins was one of the secretaries of the convention.)

In 1848, the Fishes returned to Farmington, where a new meeting of Congregational Friends had been organized. This group had a strong reform orientation, and the entire Fish family worked for causes including suffrage for women and African Americans, temperance, and fairer treatment of Native American tribes. A pacifist, Benjamin was fined and imprisoned for refusing to train for the militia. His daughter Catherine attended the 1848 Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) There, she signed the famous Declaration of Sentiments adopted by that convention.

Benjamin Fish died in 1882. He is buried alongside his wife, Sarah, in Rochester’s Mount Hope Cemetery. Catherine and Giles Stebbins are buried in the adjacent plot.

Old Barn

A barn on the Phalanx site, now a farm and animal shelter; the structure may date to the Phalanx period.

Associated Historical Events

First Convention of the Fourier Society of Rochester

August 22–23, 1843

Meeting of Fourier Society of Rochester

November 21, 1843

Rise and Fall of Sodus Bay Phalanx

1843–1846