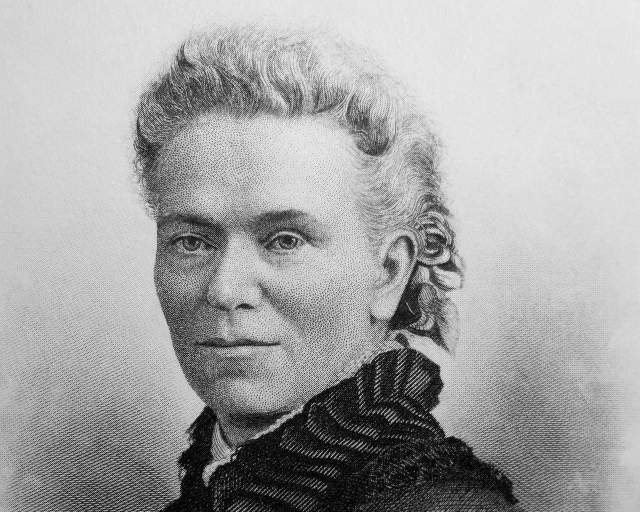

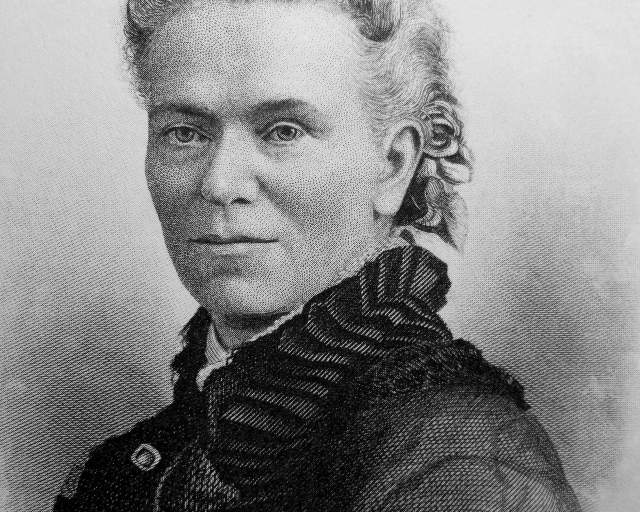

History has almost forgotten that in their heyday, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–1898) were known as "The Triumvirate" who jointly led the National Woman Suffrage Association, the radical wing of the woman’s rights movement. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman or woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women or women's.) Of the three leaders, Anthony was the most accommodating toward religion, eventually welcoming the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union into the movement. Stanton published her radical critiques of religion, such as The Woman’s Bible, only after she had established her reputation as a pillar of the suffrage movement. Gage, on the other hand, was always outspoken in challenging religion, sharply criticizing Christianity for institutionalizing discrimination against women in her best-known book, Woman, Church, and State.

Early Life. Matilda Electa Joslyn was born in 1826 at the Cicero, New York, home of Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn and his wife, Helen. She grew up in an unusually comfortable home by the standards of that time and place—and in an abolitionist home that was an active station on the Underground Railroad. Moreover, her father raised her in a novel way, teaching her physiology and anatomy, among other subjects. Even as a young girl, she would ride alongside him on his medical rounds to outlying communities.

Gage and Woman's Rights. Recently married and pregnant, Gage did not attend the first Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls (1848). In any case, the Seneca Falls conference had been billed as a regional event; it emerged as nationally important with its adoption of the Declaration of Sentiments, which had not been planned in advance.

Gage entered the woman's rights movement at the Third National Woman's Rights Convention held in Syracuse in September 1852. She made her first woman's rights speech there. This was also the first woman's rights convention attended by Susan B. Anthony. “When I entered the woman suffrage work," Gage wrote that she was "the youngest woman then in the cause.”

Gage joined the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), which favored woman suffrage, soon after its founding in 1866. The AERA foundered just three years later because of differences among more- and less-socially radical suffrage activists.

Essentially, what happened was that in May 1869, the Equal Rights Association split in two: Gage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which sought a federal woman's suffrage amendment to the Constitution. The more moderate American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone and others, sought to win suffrage for women state by state.

The NWSA's New York auxiliary, the New York State Woman Suffrage Association (NYSWSA), held its organizing convention on July 13 and 14, 1869. Gage presided and was elected secretary. The group adopted a plan of organization that Gage had designed. In 1870 Gage was elected NYSWSA president, an office she would hold until 1879. During these years NYSWSA became the most successful state-level organization in the suffrage movement.

By then dubbed "The Triumvirate," Gage, Stanton, and Anthony began work on The History of Woman Suffrage in 1876. (The third volume of the multi-volume series, the last they would co-edit together, was published in 1886.)

Unlawful Voting as a Protest. In July 1871—sixteen months before Anthony's more famous effort at voting illegally—Gage orchestrated an attempt by ten women to vote in Fayetteville. The women entered a hotel serving as a polling place. "I went down first and offered my vote," Gage later wrote to her friend and fellow reformer Lillie Devereux Blake. "I was refused on the ground that I was a married woman. Then I took down two single women who supported themselves and owned their own home … their votes were refused also. Then I took down … war widows, whose husbands had left their bones to bleach on the field of battle, in defense of their country, and they, too, were refused, and so on through the whole nine," she recounted. "With each one, I made appropriate arguments, and had a big and attentive crowd to hear me. … It created a great stir.” In doing this, Gage joined hundreds of women, including Stanton, who attempted to vote after 1868.

Before her own attempt to vote in 1872 that resulted in her arrest and trial, Anthony was a frequent guest at Gage's Fayetteville home. Anthony and Gage were then fellow radicals. It was during this period when Anthony carved her name in the windowpane of an upstairs guest room of Gage's house; the inscription remains visible today.

Gage was the only NWSA representative to attend her trial in Canandaigua.

In 1875, Gage was elected president of NWSA. During her one-year term, plans were laid for the dramatic presentation (by Anthony and Gage) of a woman's rights document at the U.S. Centennial Exposition (the first World's Fair) held at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, on July 4, 1876. The document, the Declaration of the Rights of Women, was cowritten by Gage and Stanton.

Gage attended the thirtieth-anniversary commemoration of the Seneca Falls convention, held on July 19, 1878, at the Unitarian Church on Fitzhugh Street in downtown Rochester. Also in attendance were Stanton, Lucretia Mott (aged eighty-six), Amy Post, Elizabeth Smith Miller, Sojourner Truth, and Frederick Douglass. A series of resolutions, including three radical statements drafted by Gage, were adopted. One of the Gage-written resolutions stated, "It is through the perversion of the religious element in woman, cultivating the emotions at the expense of her reason, playing upon her hopes and fears of the future, holding this life with all its high duties forever in abeyance to that which is to come, that she, and the children she has trained, have been so completely subjugated by priestcraft and superstition." After the convention, members of both NWSA and AWSA objected to the "antireligious nature" of the resolutions. The New York World excoriated them as an "illustration of the evil tendencies of the Woman’s Rights movement."

Stung by these critiques and concerned that the suffrage organizations had “ceased to be progressive,” Gage offered her critique of Christianity to a more receptive audience: a national freethinkers' convention soon to meet in the region.

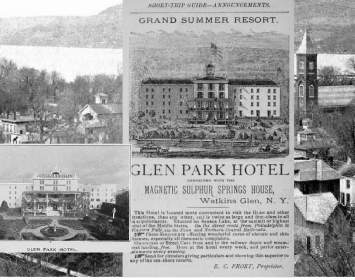

Gage's Freethought Turn. On August 24, 1878, Gage addressed the New York Freethinkers Association convention held at Watkins Glen, then Watkins. There she gave her first brief freethought lecture, whose thesis became the core of her best-known statement on women and religion (see below).

The year 1880 was one of triumph and betrayal. New York State having allowed women to be elected to school boards and to vote in school board elections, Gage again orchestrated a large turnout of women to vote in Fayetteville. But this time, none of the 102 woman voters was turned away. Among the three women elected to four open board seats was Gage's eldest daughter, Helen. During the same year, Gage learned that Anthony and Stanton had given a press interview in which they claimed sole credit for The History of Woman Suffrage and mentioned nothing about Gage's co-equal role as author and co-editor. This would not be the last time Anthony and Stanton would seek to distance themselves from Gage's radicalism.

Nonetheless, the first volume of The History would see print in 1881. Gage was the sole author of three chapters. The first, “Preceding Causes,” described women’s achievements through history, profiling ninety-three accomplished women, including Queen Elizabeth I. The second was titled “Woman in Newspapers.” The closing chapter, “Woman, Church, and State,” further developed the ideas she had presented at Watkins in 1878.

The second volume of The History appeared in 1882. Gage was outraged to discover that her chapter describing women’s efforts to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment had been altered by Stanton and Anthony, minimizing her own efforts to vote (as well as those of hundreds of other activists), instead emphasizing Anthony’s alone. But Gage was unable to prove this because she had mislaid her original manuscript.

In 1886, Gage set to further research to expand “Woman, Church, and State” into a book. In the same year, Stanton began work on The Woman’s Bible. With the two thus occupied, Anthony—who objected to their “church diggings”—was free to expand her own, by then markedly more conservative, profile in the suffrage movement. (Gage and Anthony had once been fellow radicals; now Gage and Stanton were the radicals.)

Reunification and Its Bitter Aftermath. After two decades of separation, Anthony secretly reached out to Lucy Stone to heal the rift between NWSA and AWSA. In 1890, the organizations merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The seemingly sudden reunification had in fact been carefully negotiated by Anthony, mostly behind the backs of both Stanton and Gage.

Anthony sought a suffragism that was less culturally radical—and especially, less critical of religion. Stanton and Gage found themselves sidelined from leadership. Yet Stanton's reputation was so strong that Anthony persuaded her to accept a figurehead presidency of NAWSA starting in 1890. This precipitated a break with Gage, who had counseled Stanton to stand firm in resisting Anthony's veer toward moderatism.

Gage would take no further part in the suffrage movement. Furious, she launched a new “antichurch organization,” the Women’s National Liberal Union (WNLU). In January 1890, Gage published the only issue of WNLU’s newspaper, The Liberal Thinker, announcing a February 24–25 convention in Washington with Stanton as keynote speaker. The February convention took place at the Willard House hotel, with about seventy persons from twenty-seven states attending. Stanton, who had promised to keynote, was a no-show, having boarded a ship for Europe five days before—after addressing a convention of Anthony's NAWSA.

Gage's convention attracted more press attention than Anthony's had. Even so, Gage could not muster enough financial support to keep the WNLU and The Liberal Thinker operating. In fact, Gage's personal finances were so desperate that she accepted a stingy offer by Anthony to buy out her one-third share in The History of Woman Suffrage. Gage later complained of feeling cheated by Anthony.

Gage's Masterwork. In 1893, Gage's masterwork, the book Woman, Church, and State, was published by Charles Kerr, a Chicago socialist publisher. The book earned both positive and negative reviews in the mainstream press; freethinkers delightedly embraced it. Gage even received a fan letter about the book from Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy. Still, Gage was dissatisfied with the large number of typographical errors in Kerr's edition. Later the same year, Gage chose the Truth Seeker Company (whose late founder, D. M. Bennett, had been arrested at the Watkins conference of 1878, after which the company published a capable transcript of the convention proceedings) to issue a second edition. This edition is considered definitive.

Also in 1893, Gage was honorarily adopted into the Mohawk Nation’s Wolf Clan. Gage received the Wolf Clan name Ka-ron-ien-ha-wi, meaning “She who holds the sky." Gage scholar Sally Roesch Wagner chose that phrase as the title for her Gage biography.

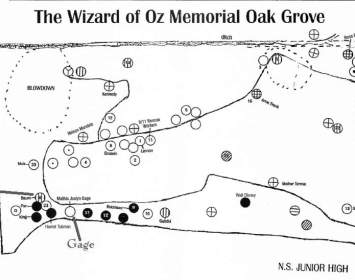

The Baum Legacy. Perhaps the most surprising legacy of Gage's feminism and freethought appears in the works of L. Frank Baum, husband of her daughter Maud and a frequent visitor to Gage’s Fayetteville home.

In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and many other children’s books, L. Frank Baum presented a remarkable assortment of strong female characters and championed critical thinking over obscurantism and worshipfulness. (The moment when Toto goes "behind the curtain" and proves that the Wizard is no wizard at all is only the best-known appearance of this classic debunking device in Baum’s work.)

After her husband died in 1884, Gage spent the last fourteen winters of her life with Frank and Maud at their Syracuse home; their 1887–1891 home in Aberdeen, South Dakota; and from 1892 until her death in their Chicago home. During these visits, she conducted suffrage work and worked on her books.

Gage's Death. Gage died at Frank and Maud’s Chicago home on March 18, 1898. She was cremated, a radical option at a time when most American Christians insisted on burial, fearful that if their bodies were burned they might be unable to participate in the Last Judgment. Gage's ashes were buried in the Fayetteville Cemetery beneath a rough-hewn headstone inscribed with her best-remembered saying: "There is a word sweeter than mother, home, or heaven. That word is Liberty."

Among the members of the suffrage movement’s leadership “Triumvirate,” Gage was the most consistently and outspokenly critical of religion.

Eroding Gage's Memory: "The Matilda Effect." Stanton outlived Gage by four years, Anthony by eight. They used this time to burnish a historical remembrance that celebrated themselves and, bluntly, sidelined Gage. Both Stanton and Anthony burned their papers shortly before their deaths, ensuring that The History of Woman Suffrage would stand as the sole "insider" account of the movement's early years.

History’s later treatment of Anthony, Stanton, and Gage is most revealing. Early twentieth-century suffragists tended to look back on Anthony, a closeted freethinker who sought to keep Christian groups in the suffrage movement, as its sole founding leader. Stanton, who revealed her infidel views only late in life, having already established her reputation as a suffragist, was almost forgotten until her rediscovery by second-wave feminists of the 1960s. Gage, who had been critical of religion throughout her suffrage career, was largely excluded from history until 1972, when feminist scholar Sally Roesch Wagner arranged for an influential reprinting of Woman, Church, and State.

Gage's rehabilitation in the historic record gained speed in the 1990s and continues today.

In 1993, science historian Margaret W. Rossiter coined the term “the Matilda Effect” to denote the process by which “women scientists … have been ignored, denied credit, or otherwise dropped from sight.” Rossiter chose Gage as the avatar for such women, even though Gage was a non-scientist.

Gage Home and Museum. Since 2011, Gage’s Fayetteville home has been open to the public as a center for social justice dialogue and a full-time Gage museum. A new generation of historians and feminist activists are rediscovering Gage’s unique vision and wit.

For more information on Matilda Joslyn Gage see The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation.

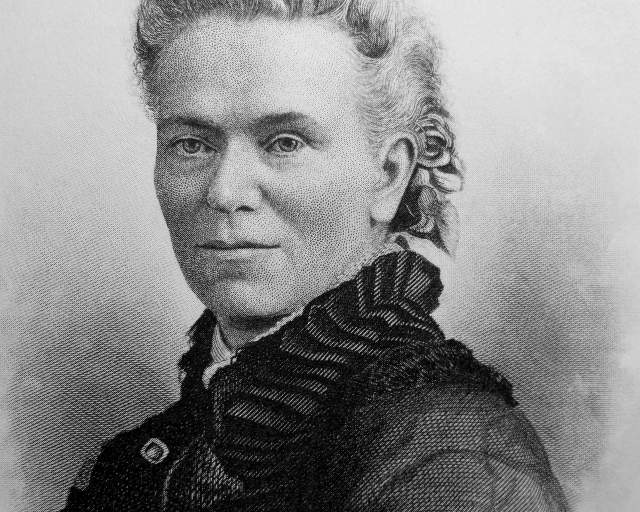

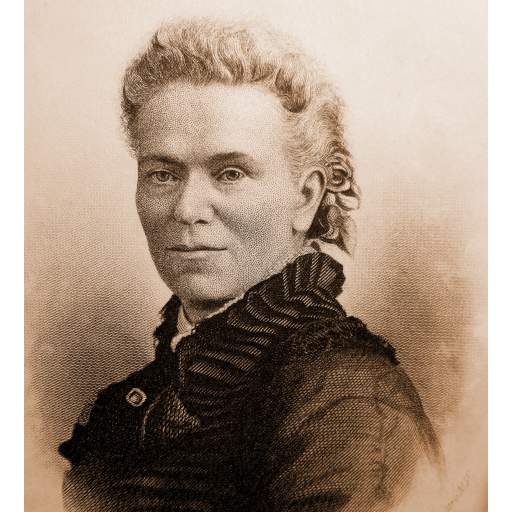

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage.

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

Third National Woman’s Rights Convention

September 8–10, 1852

1878 Woman's Rights Convention

July 19, 1878

Second New York Freethinkers' Association Convention

August 22–25, 1878

Matilda Joslyn Gage Speaks on Woman's Rights at Sage College

February 26, 1881

Sixth New York Freethinkers' Association Convention

August 23–27, 1882

Early Life of L. Frank Baum

1861–1888

Twenty-Second NY State Suffrage Convention

December 16–18, 1890

Death of Matilda Joslyn Gage

March 18, 1898