Mary Edwards Walker, M.D., (1832–1919) was one of the first female physicians to serve in the U.S. armed forces and, to date, the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor. An ardent abolitionist and woman’s rights advocate, she focused especially on dress reform and on expanding women’s role in the political process. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class. Later practice was to use the plural, woman's.)

Early Life. She was born in Oswego on November 26, 1832, the youngest of seven children of physician Alvah Walker and his wife Vesta Whitcomb Walker. (Her mother hailed from the same family as Margaret Whitcomb, a grandmother of freethinking orator Robert Green Ingersoll; this made Mary a second cousin of Ingersoll’s.) Though Christians, the elder Walkers were very much “free thinkers” and shared an advanced social outlook. They were determined that their six daughters should enjoy the same educational opportunities as their son—something they could easily ensure, having donated Oswego’s first free school house. Outside of school hours, the Walkers encouraged their children to think independently and allowed their girls to wear less restrictive boys’ clothing when performing farm labor.

Alvah Walker encouraged Mary Walker to study his anatomy and physiology books, exposing her to medical literature at an early age. (Abolitionist Hezekiah Joslyn took a similar approach to the education of his only daughter, the future suffrage leader Matilda Joslyn Gage; Elizabeth Cady Stanton, too, enjoyed a somewhat similar upbringing). Walker developed a strong interest in medicine and after working a few years as a teacher, paid her own way through Syracuse Medical College. She graduated with honors in 1855, the sole woman in her class.

As a young woman, Walker belonged to the Methodist Church, but she "later severed her association." Her brother, Alvah Jr., was a lifelong agnostic.

A Radical Emerges. Walker married a fellow medical student in November 1855. At the wedding ceremony she wore a mid-length skirt over trousers, omitted the word obey from her vows, and chose not to take her husband’s surname. The couple established a joint medical practice in Rome, New York. The practice was unsuccessful, largely because few patients would trust a woman doctor. (The couple soon separated because of the husband’s infidelity; when divorce came in 1869, it was a formality.)

As should be apparent, Walker had already begun to experiment with alternative modes of dress. In 1857, she spoke at an early dress reform convention in Canastota; one of her fellow speakers was abolitionist philanthropist Gerrit Smith, who (among other things) read a most cordial letter to the convention from his cousin, Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

War and Aftermath. By 1861, Mary Walker’s everyday attire consisted of trousers with suspenders under a knee-length dress. "The greatest sorrows from which women suffer to-day,” she later wrote, “are those physical, moral, and mental ones, that are caused by their unhygienic manner of dressing!" Her clothing caused her to be misunderstood and on at least one occasion physically attacked by townspeople. But her example, and her increasingly prolific speaking and writing, gave her a high stature among reformers and female physicians alike. In 1860, she was elected Third Vice President at the National Dress Reform Association’s fourth annual meeting in Waterloo. At the same organization’s 1863 conference in Rochester, she was elected Sixth Vice President though she was already off at war.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Mary Walker had volunteered her services as a physician to the Army. Despite her medical degree, she was initially permitted to practice only as a nurse. Eventually she secured positions as an unpaid field surgeon, serving at the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chickamauga. In September 1863, the Army of the Cumberland employed her as a “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon (Civilian),” making her the first woman employed as a surgeon by the U.S. Army. She was captured by Confederate troops in April 1864, held prisoner, and released that August.

Walker quickly resumed her activism for suffrage, dress reform, temperance, and women’s role in politics. On October 24, 1864, she spoke at a regional Democratic Party rally in Oswego’s Doolittle Hall.

On January 24, 1866, she received the Medal of Honor from President Andrew Johnson, the only woman to be so recognized. She invariably wore the medal when appearing in public.

Walker on Religion. In 1871, Walker published a book, puzzlingly titled Hit. The book’s final chapter dealt with religion. In it, Walker made clear that she was no unbeliever, but rather very religiously liberal for the time.

She described religion as the result of children projecting into the cosmos the characteristics of their parents. She concluded that "there is something good in all [r]eligious beliefs" and so "there should be a quiet toleration" toward those who worship differently. Still, she warned, "any [r]eligion that gives the wife a servile position, is beneath the great plans of Deity." Closing her discussion of faith, she declared, "No [r]eligion is true and genuine, it matters not what church its representatives belong to, unless it is something that makes homes happy and ennobles life generally."

From Bloomers to Men's Formal Wear. Walker continued wearing Bloomers, the reform costume invented by Elizabeth Smith Miller in 1851, long after most other suffragists abandoned the costume because it sparked controversies they found distracting from their suffrage work. Citing its great practicality, Walker kept wearing the “Bloomer costume” until the late 1870s. After that, she began simply dressing in men’s clothing. She was arrested for impersonating a man on several occasions.

In 1881, Walker called on her cousin Robert Green Ingersoll at his home at 25 Lafayette Square in Washington, D. C. She was wearing Bloomers. In the words of his biographer C. H. Cramer, Ingersoll "was a stanch defender of women's rights, but he was rigidly orthodox on the subject of female attire." Though famous for hospitably receiving every caller, from the famous to the cranks, Ingersoll denied Walker entrance.

1881 also saw Walker campaign unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate; in 1890, she ran as a Democratic candidate for Congress, each time unsuccessfully. She attended several Democratic conventions to which she had not been credentialed by the simple expedient of declaring herself a delegate.

Her distinctive mode of dress became so famous that in November 1895, when a woman in man’s clothing was seen debarking from a steamship, the New York Evening World falsely announced that Mary Walker had just come back from Europe, traveling incognito!

Later Life. Looking back on her career in 1897, she declared: "I am the original new woman ... Why, before Lucy Stone, Mrs. Bloomer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were ... before they were, I am. In the early forties, when they began their work in dress reform, I was already wearing pants.”

In 1917, following a Congressional reform that changed the terms under which the Medal of Honor could be awarded, she was retroactively removed from the list of awardees. She refused to surrender the medal, and continued wearing it in public until her death.

She lived most of her life in her birthplace on Bunker Hill Road, which was lost to fire years after her death. In old age, she moved in with a neighboring family, the Dwyers. She died in the Dwyer residence on February 21, 1919, aged 86. No church service was held; a memorial meeting held at her birthplace and longtime home did not include a single hymn.

Legacy. In 1977, thanks to patient lobbying by her family and a Congressional reassessment of her wartime actions, Mary Walker’s Medal of Honor was restored.

The site of Walker’s birthplace now bears a historical marker. The Dwyer residence has been replaced by a suburban house; there is no marker. A statue of her stands in front of the Oswego Town Hall; inside the building are some displays about her life. In addition, there is a Mary Walker Health Center on the campus of the State University of New York (SUNY) at Oswego.

Mary Edwards Walker

Mary Edwards Walker, photographed in her Civil War uniform in 1865.

Mary Edwards Walker

Undated photo of Mary Edwards Walker in uniform.

Mary Edwards Walker in Old Age

Mary Edwards Walker in old age, wearing men's formal attire as was her practice later in life.

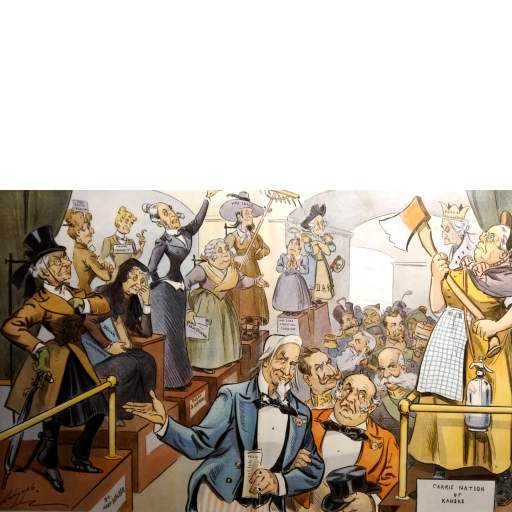

Walker in 1901 Misogynist Cartoon

This 1901 Louis Dalrymple cartoon from the humor periodical Puck urges the upcoming "Buffalo Exposition" (the Pan-American Exposition, a world's fair to be held at Buffalo, New York) to "have a chamber of female horrors." Feminist, suffragist, and temperance leaders of the time are satirized.

Front-row figures (on pedestals), left to right:

- Dr. Mary Walker;

- Attorney, politician, and suffragist Belva Ann Lockwood;

- Susan B. Anthony;

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton;

- Suffragist, temperance activist, and populist Mary Elizabeth Lease;

- Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy;

- A generic member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (D. A. R.);

- The "Queen of Holland Dames" (Lavinia Dempsey, an elderly radical who as an act of rebellion in 1898 was crowned the upstart "queen" of a Dutch-American sororal organization; and

- Anti-alcohol crusader Carrie Nation.

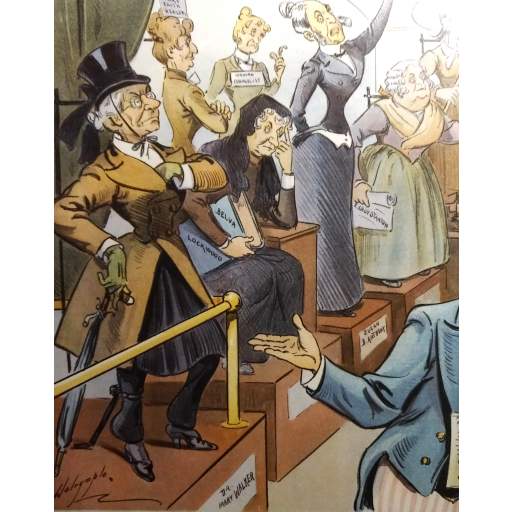

"Female Horrors" Detail

Detail of 1901 Puck cartoon features (front row, left to right) Mary Edwards Walker, Belva Lockwood, a poor likeness of Susan B. Anthony; and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In the background stand a "faith healer" and a "woman evangelist."

Associated Causes

Associated Historical Events

Birth of Mary Edwards Walker

November 26, 1832

First National Dress Reform Association Convention

January 7–8, 1857

Mary Edwards Walker Addresses Major-Party Political Convention

October 24, 1864

Death of Mary Edwards Walker

February 21, 1919