In nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America, birth control was a radical, even frightening idea. Activists, many drawn from the freethought movement, argued that "science ... should put it in the power of woman to decide whether she will or will not become a mother" (the quotation is from agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll). To put an argument for birth control—much less information about actual birth control methods—into print was to invite prosecution under the era’s opressive obscenity statutes.

Prominent birth-control advocates included Charles Knowlton, who was jailed for selling his 1830s birth control tract Fruits of Philosophy. Thousands of copies of this tract were sold throughout the nineteenth century, with sellers being arrested and tried for obscenity on multiple occasions in the United States and England. In many ways, Knowlton’s successor was the American medical doctor Edward Bliss Foote, who published Medical Common Sense, an 1864 book that offered more reliable birth control information than Knowlton’s tract had provided. Foote was largely precluded from selling his book by mail because of restrictive anti-obscenity laws. In the twentieth century, of course, Corning native Margaret Sanger would fight for the right to distribute scientifically valid birth control information. She would go on to found Planned Parenthood and support research that would develop the famous birth-control pill of the 1960s.

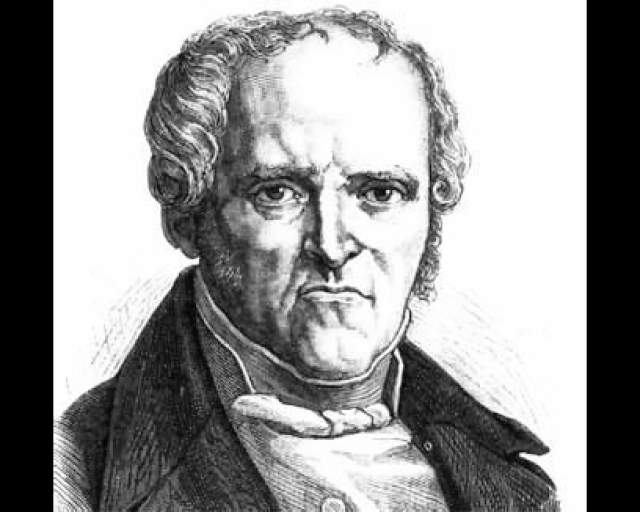

Frances "Fanny" Wright (1795–1852) was a prominent early sex radical, as well as being an abolitionist, feminist, and freethinker. She was one of the first women to address audiences of mixed sex across the United States, including in west-central New York State, and led a life of sufficient sexual liberation to make her a continuing object of scandal and controversy, though her living arrangements would scarcely be controversial today.

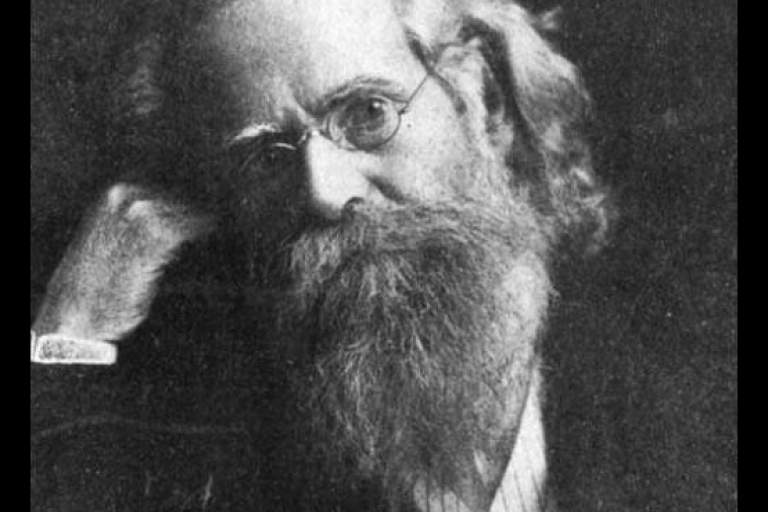

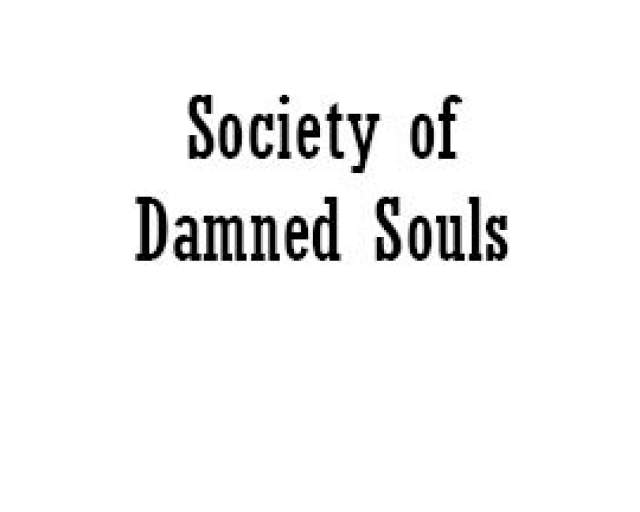

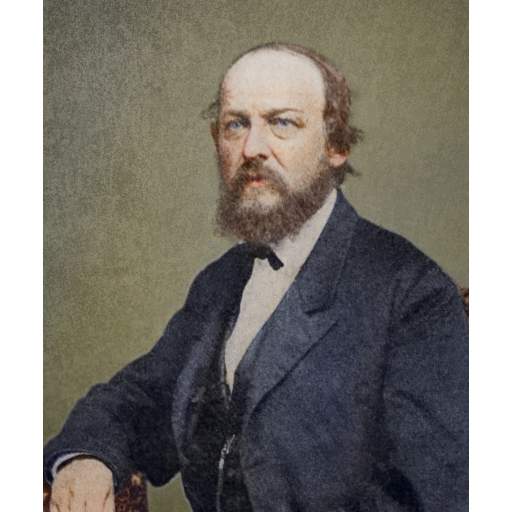

Nineteenth-century sex radicals were a diverse lot. One of the most thorough-going was free-love activist and birth control advocate Moses Harman (1830–1910), pictured above. He argued that each woman should have unfettered freedom to choose her sex partners, in part because that might produce superior children compared with those conceived in what scholar Julie Harrada called "a coerced and loveless marriage where the woman was legally viewed as property." Obviously, such a position placed Harman far outside the limits of Christian orthodoxy; the result was substantial overlap between the sex-radical and freethought communities.

Other noteworthy sex radicals included Stephen Pearl Andrews, who founded Modern Times, a non-Fourierist Utopian community on Long Island where women’s labor was valued at the same rate as men’s and individuals were free to arrange their intimate relationships as they pleased. As its reputation as a "free-love community" spread, Modern Times attracted an insupportable number of opportunists and undesirables; the community collapsed after several years of operation.

Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennessee Claflin published a radical feminist weekly newspaper, Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly, which Stephen Pearl Andrews edited for a time. Woodhull campaigned for, among many other things, more liberal divorce laws so that women could more easily divorce abusive and alcoholic husbands. In 1872, she became the first woman candidate for U.S. president on the Equal Rights Party platform.

Other noteworthy sex-radical periodicals were The Word, published by Ezra and Angela Heywood, and Lucifer: The Light Bearer, edited by Moses Harman. (Harman’s daughter Lillian and her life partner, Edwin C. Walker, were jailed for putting their radical principles into practice by living together by mutual consent without benefit of matrimony.) In 1876, Harman published Cupid’s Yokes, an idiosyncratic pamphlet that called for marriage reform and mentioned birth control in very vague terms.

Much sex-radical activism occurred on the East Coast or in the Midwest. But sex radicalism helped to shape one important incident on the Freethought Trail. It had to do with Cupid’s Yokes.

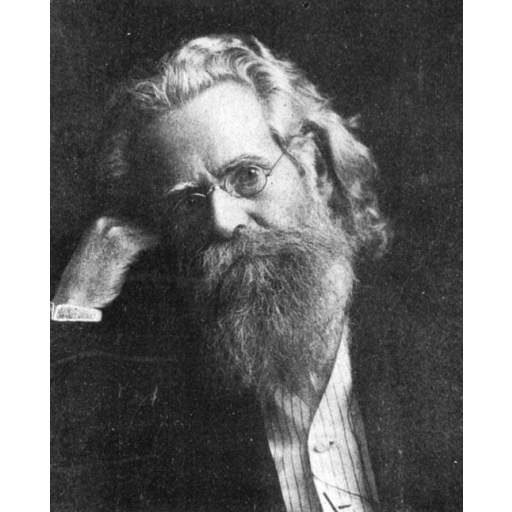

Copies of Cupid’s Yokes were sold at the 1878 convention of the New York Freethinkers’ Association at Watkins, later Watkins Glen. This led to the arrest of atheist publisher D. M. Bennett, who was staffing someone else’s literature table as a brief favor, along with two other activists. This set in motion a complex series of events that led, ultimately, to a court decision that would define the U.S. legal standard for obscenity until 1957, and to a thirteen-month prison term for Bennett that hastened his death.

Anarchist and sex radical Emma Goldman, who emigrated to Rochester in 1886, moved to New York City and began her radical career in 1889. By the turn of the twentieth century she emerged as a major radical figure, advocating birth control and sex radicalism in her speeches as she practiced free love in her life.

Frances "Fanny" Wright

Frances "Fanny" Wright (1795–1852) was a prominent early sex radical, as well as being an abolitionist, feminist, and freethinker. She was one of the first women to address audiences of mixed sex across the United States, including in west-central New York State, and led a life of sexual liberation by the standards of her time.

Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Woodhull (1838-1927) and her sister Tennessee Claflin published a weekly radical-feminist weekly newspaper, Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly. Woodhull campaigned for, among many other things, more liberal divorce laws so that women could more easily escape abusive and alcoholic husbands. In 1872, she became the first woman candidate for U.S. president on the Equal Rights Party platform.

Moses Harman

Moses Harman (1830-1910), editor of Lucifer, The Light-Bearer, one of the nineteenth century's most controversial sex-radical publications.

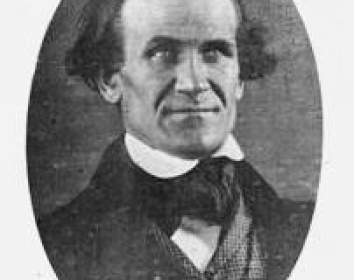

D. M. Bennett

D. M. Bennett (1818-1882) published one of freethought's national newspapers of record, The Truth Seeker. At an 1878 freethought convention at Watkins, now Watkins Glen, he was arrested for selling copies of Ezra Heywood's marriage-reform tract Cupid's Yokes. This arrest led indirectly to an obscenity case involving decency crusader Anthony Comstock, agnostic orator Robert G. Ingersoll, President Rutherford B. Hayes, and others, which ultimately established the Hicklin standard, the repressive legal definition of obscenity that prevailed in U.S. law until 1957.

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

Rise and Fall of Sodus Bay Phalanx

1843–1846

Rise and Fall of Skaneateles Community

1843–1846

Second New York Freethinkers' Association Convention

August 22–25, 1878

Birth and Early Life of Margaret Sanger

1879–1905

Emma Goldman Speaks on 'The Birth Strike'

December 21, 1914

Emma Goldman Speaks on 'Free or Forced Motherhood'

December 19, 1916

Scandal of the Society of Damned Souls

1926–1927