Given the constricting excess of middle-class women’s clothing in nineteenth-century America (up to fifteen pounds of tight corsets, heavy skirts, and petticoats), it is hardly surprising that reformers in various parts of the country strove to promote more practical and healthful clothing styles so that women could be more active outside the home. Woman’s rights campaigners from west-central New York State were not the first to seek reform in this arena, but they were among the most prominent. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's.)

Early Origins. "Reform dress," as it was called, seems to have made its first appearance at New Harmony, Indiana, at a Utopian intentional community founded by Robert Owen in 1824. (Like many such communes, New Harmony lasted just three years.) One of its innovations was the introduction of trousers for women, worn beneath comparatively short dresses. (The style may have been inspired by similar, practical clothing styles long worn by Haudenosaunee [Six Nations Native American] women.) New Harmony was also founded on freethought principles; pioneer feminist and freethought lecturer Frances Wright twice visited the community in 1825.

In the decade after New Harmony failed, abolitionist Sarah Moore Grimké criticized the "gewgaws and trinkets" and "ribbons and laces" then demanded by fashion as obstructions to women’s betterment, but she is not known to have worn reform dress herself.

In 1848, the Christian Perfectionist Oneida Community of Oneida, New York, resurrected reform dress, this time featuring short dresses over pantaloons. Similar initiatives were taken at other non-freethinking intentional communities including Hopedale (Hopedale, Massachusetts), the North American Phalanx (near Red Bank, New Jersey), Brook Farm (West Roxbury, Massachusetts), Modern Times (Long Island, New York), and Ruskin Commonwealth (Dickson County, Tennessee).

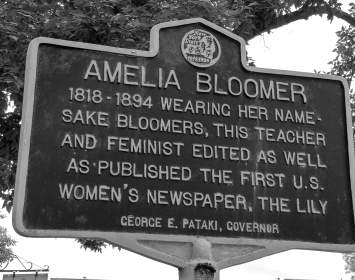

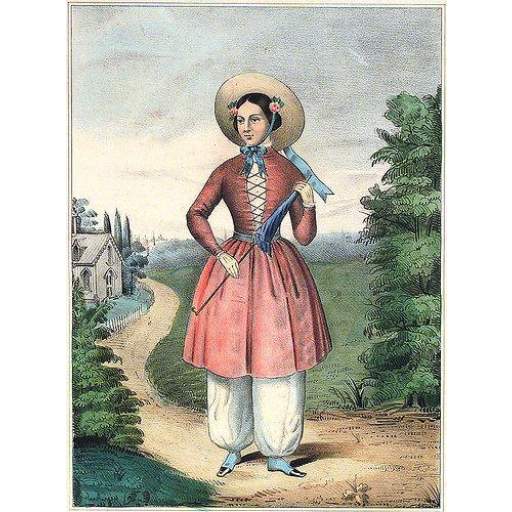

Reform Dress among Suffragists. The most iconic phase of reform-dress activism occurred among woman’s rights and suffrage activists in west-central New York. Early in 1851, Elizabeth Smith Miller of Peterboro, the daughter of abolitionist philanthropist Gerrit Smith, designed the definitive reform dress style: a roughly knee-length skirt worn over Turkish-style pantaloons (pictured below). Accounts suggest that Miller wore the reform style while visiting Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Seneca Falls; Stanton immediately copied the garment. (At this time middle-class women made most of their own clothing, often without the benefit of patterns; a new style could spread rapidly by simple imitation.) In short order, Amelia Jenks Bloomer, also of Seneca Falls, made her own reform costume. Bloomer, editor of the temperance and woman’s rights paper The Lily, had been jousting with critics over unconfirmed reports of women wearing similar costumes in public on the East Coast. Considering the new style superior to traditional women’s fashions, she began to promote Miller’s version of reform dress in her paper.

Later in spring 1851 Miller, Stanton, and Bloomer stepped out onto the streets of Seneca Falls, each of the three wearing a comparatively short skirt over pantaloons, which they called "freedom dress." This was a masterwork of guerrilla theater; not only did their promenade cause a local sensation, it earned reportage in newspapers across the nation including the New York Tribune, the Boston Carpet Bag, and the Chicago Tribune. Reporters competed to coin their own witty names for the new style. What stuck was "Bloomers," a nod toward Amelia Bloomer. To this day, Amelia Bloomer is often misidentified as the inventor of a reform fashion she did not invent, but rather did the most to publicize.

Stanton, Bloomer, Miller, and others built organizations to campaign for woman’s rights. But Stanton thought dress reform required no such formal organization. She expected that the example set by prominent women adopting reform apparel would prompt countless others to adopt the style on their own. While matters didn’t work out that way, Stanton was successful in persuading women’s rights campaigners Lucy Stone and Sarah and Angelina Grimké to take up the costume. One of Stanton’s final conquests was Susan B. Anthony, who bobbed her hair and donned Bloomers for a December 1852 lecture in Auburn.

Reform dress for women touched a nerve, sparking anger and ridicule. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s husband, Henry Brewster Stanton, almost lost his 1851 bid for re-election to the New York State Senate because of his wife’s costume. Newspaper cartoons sneered that if women took on masculine characteristics by wearing pantaloons, men would don dresses and become dependent and "feminized." Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, otherwise a strong supporter of the women’s movement, stridently urged abandonment of reform dress. Indeed, among male supporters of women’s rights, only Gerrit Smith supported pantaloons reform dress. Traditional women’s garb, he complained, "both marks and makes their impotence." So intense was Smith's support that it seemed he thought pantaloons alone would make women equal.

It soon became apparent to woman’s rights advocates that the Bloomer costume was a distraction; critics would focus on their apparel rather than listening to them about why women deserved the vote. By the end of 1853, Stanton abandoned the Bloomer costume. She soon persuaded Lucy Stone to do likewise. Susan B. Anthony, who had been slow to take up Bloomers, was also slow to discard them, continuing to wear the style until mid-1854. As for Amelia Jenks Bloomer, she continued to wear short skirts over pantaloons until 1858, when she gave it up for a new fashion, the light-weight wire hoop skirt. (By that time she had moved with her husband to Council Bluffs, Iowa.) The last suffragist to forsake the Bloomer costume was Elizabeth Smith Miller, who continued wearing it, in part to please her father, until as late as 1861.

Though suffragists no longer wore the reform costume, the media and the public continued to associate it with the campaign for suffrage. As late as 1866, a New York Times reporter covering a woman’s rights convention expressed surprise to see "no woman in attendance wearing the bloomer or ’short’ dress." Yet most suffragists had given up the costume more than ten years previously!

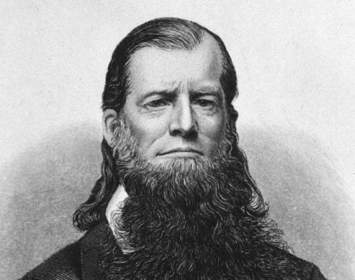

Reform Dress among Hydropathists; Rise of the NDRA. While suffragists were forsaking the Bloomer costume, another group took it up: practitioners of water cure (hydropathy), a then-popular quack therapy that involved mineral-water baths, steam baths, and pure foods, often administered in a residential sanitarium setting. In February 1856, abolitionist and Town of Sempronius hydropathist James Caleb Jackson founded the National Dress Reform Association (NDRA). An abolitionist and health reformer who also invented Granula, the first dry whole grain breakfast cereal, Jackson claimed, controversially, to have invented pantaloons reform dress in 1849—two years before Elizabeth Smith Miller created the Bloomer costume—as a garment for patients at his spa. Then again, Jackson also claimed that long skirts made it impossible for a woman to "keep her uterus [in] its proper place." (In fact, it is likely that Jackson knew about the experiments with reform dress in the Oneida Community. Despite his implicitly challenging Elizabeth Smith Miller's claim to have invented the Bloomer costume, Jackson maintained a close relationship with Elizabeth’s father, Gerrit Smith; the two knew each other well from abolition activism in the Liberty Party in the 1840s.)

With the NDRA, dress reform now enjoyed the institutional infrastructure that suffragists hadn’t thought it needed. The NDRA redubbed the Bloomer as "the American Costume," touting its health benefits. The NDRA was generally cool toward suffrage, arguing that a revolution in women’s apparel, not the vote, was what was most needed to make women free—a position much like that held by Gerrit Smith.

The Sibyl: A Review of the Tastes, Errors and Fashions of Society, was also founded in 1856. The independent newspaper edited by Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck, campaigned in support of NDRA’s cause.

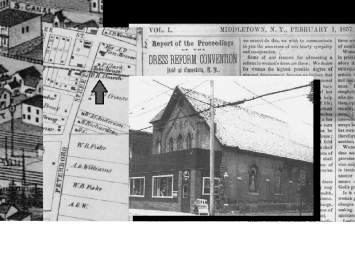

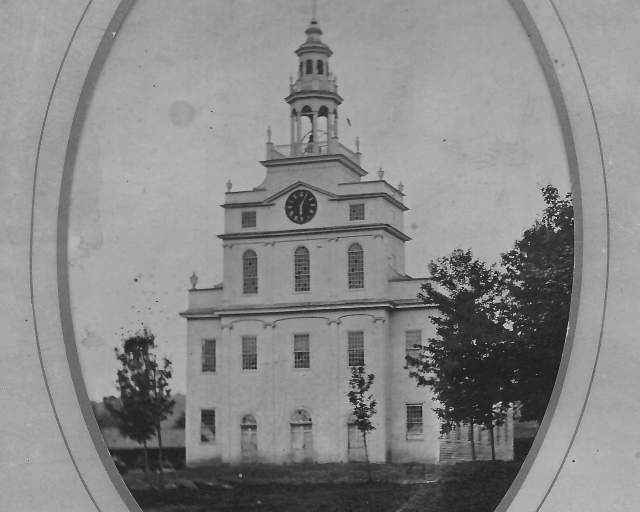

Later in 1856, the first annual meeting of the NDRA occurred in Homer, New York, at the Congregational Church.

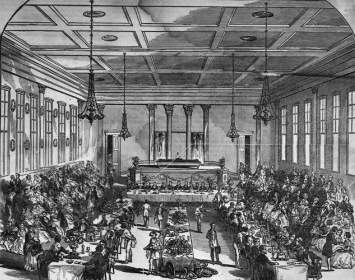

The NDRA held its first national convention at the Dutch Reformed Church in Canastota on January 7–8, 1857, with Jackson presiding. Gerrit Smith attended and participated enthusiastically; "no other convention has so great claims on me," wrote the philanthropist and prolific attender of conventions. The choice of Canastota, but seven miles north of Gerrit Smith’s home in Peterboro, presumably reflected Smith’s support for the event. The NDRA convened each year until 1861 and intermittently during the Civil War. (The Sibyl ceased publication in 1864.)

Fall of the NDRA and Subsequent Activism. The NDRA collapsed at its final convention, held June 21, 1865, at Rochester's Corinthian Hall. There Jackson and Hasbrouck, then the group’s president, had a bitter public spat over who was in charge of the proceedings.

After the fall of the NDRA, the cause of pantaloons dress reform was taken up for about a decade by the Seventh Day Adventist church. The Adventist enthusiasm for reform dress ended during the late 1870s.

Also during the 1870s, New Jersey dress reformer Mary E. Tillotson—a former NDRA member who additionally attended the 1878 and 1882 freethought conferences in Watkins (now Watkins Glen)—organized the American Free Dress League. The organization endured for only three years.

Finally, in 1881, the Oneida Community broke up. An early adopter of pantaloons dress reform, having taken it up in 1848, the Oneida Community would be the last institution to embrace short dresses and pantaloons.

With the 1890s came greater interest in clothing suited to women’s athletics and especially for riding that hugely popular new fad, the bicycle. Media at the time often observed that the "wheelwoman of the 1890s" often wore a costume almost identical to, yes, Bloomers.

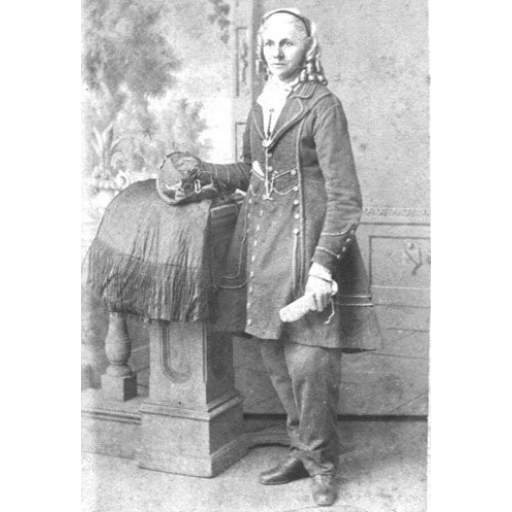

Independent Dress Reform: Mary Edwards Walker. Independent from the dress reform movement as such is the individual example of dress reformer, feminist, and freethinker Dr. Mary Edwards Walker (1832–1919). Walker had been nineteen years of age when Elizabeth Smith Miller created the Bloomer costume. When Walker spoke at the 1857 convention in Canastota, she had already earned a medical degree and begun wearing trousers. In 1860, she was elected Third Vice President at the NDRA’s fourth annual meeting in Waterloo. At the organization’s 1863 conference in Rochester, she was elected Sixth Vice President though she was serving in the Civil War. She became the first woman employed as a surgeon by the U.S. Army and in 1866, received the Medal of Honor, to this day the only woman so recognized. Walker continued to wear the Bloomer costume until the 1870s, when she abandoned it for the wardrobe she would prefer for the rest of her life: upper middle-class male attire, including trousers, coat, vest, and top hat.

"Among the crusades attempted by antebellum Americans, pantaloons dress reform had perhaps the narrowest appeal," wrote historian Gayle V. Fischer. Nonetheless, its chronicle adds a fascinating dimension to the Freethought Trail.

Bloomer costume

Period illustration of a Bloomer costume. The image may depict Elizabeth Smith Miller.

Mary E. Tillotson

Independent dress reformer Mary E. Tillotson hailed from the Utopian community of Vineland, New Jersey. In the 1870s she founded the American Free Dress League, which operated for three years. On August 22, 1878, she addressed the second convention of the New York Freethinkers Association in Watkins, later Watkins Glen.

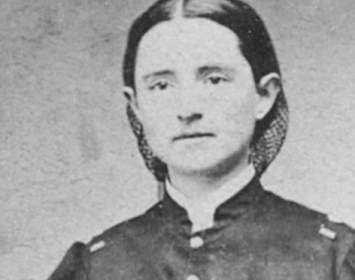

Mary Edwards Walker

Mary Edwards Walker took up the cause of dress reform independently. In this photo, she wears her Civil War-era uniform (featuring, out of shot, Bloomer-style pantaloons) and the Congressional Medal of Honor awarded for her war service; later in life, she usually dressed in formal menswear.

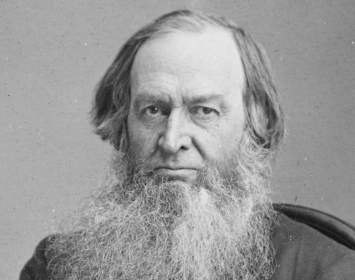

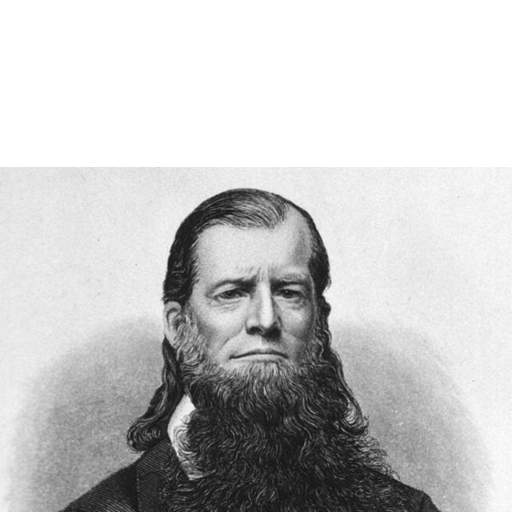

James Caleb Jackson

Former abolitionist and "water cure" quack James Caleb Jackson (1811–1895) founded the National Dress Reform Association (NDRA) in 1856, taking up the cause of more practical dress for women just as suffrage activists were abandoning it.

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

Birth of Mary Edwards Walker

November 26, 1832

First Annual Meeting of the NDRA

June 18 - 19, 1856

First National Dress Reform Association Convention

January 7–8, 1857

Final National Dress Reform Association Convention

June 21, 1865

Death of Mary Edwards Walker

February 21, 1919