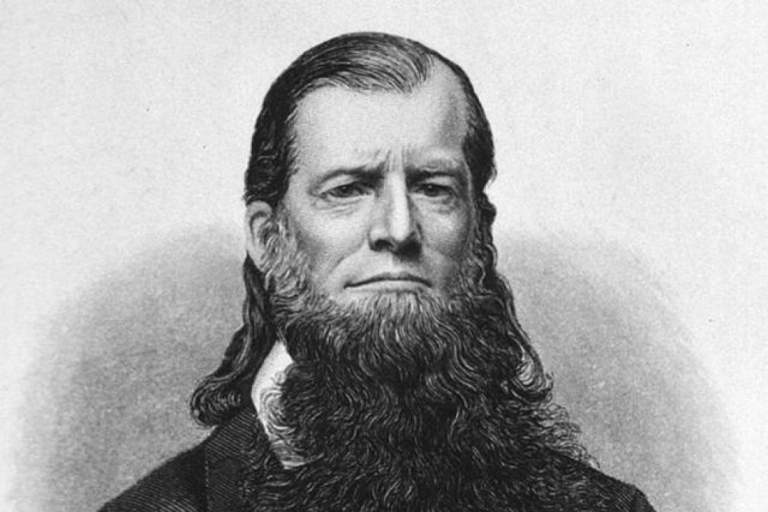

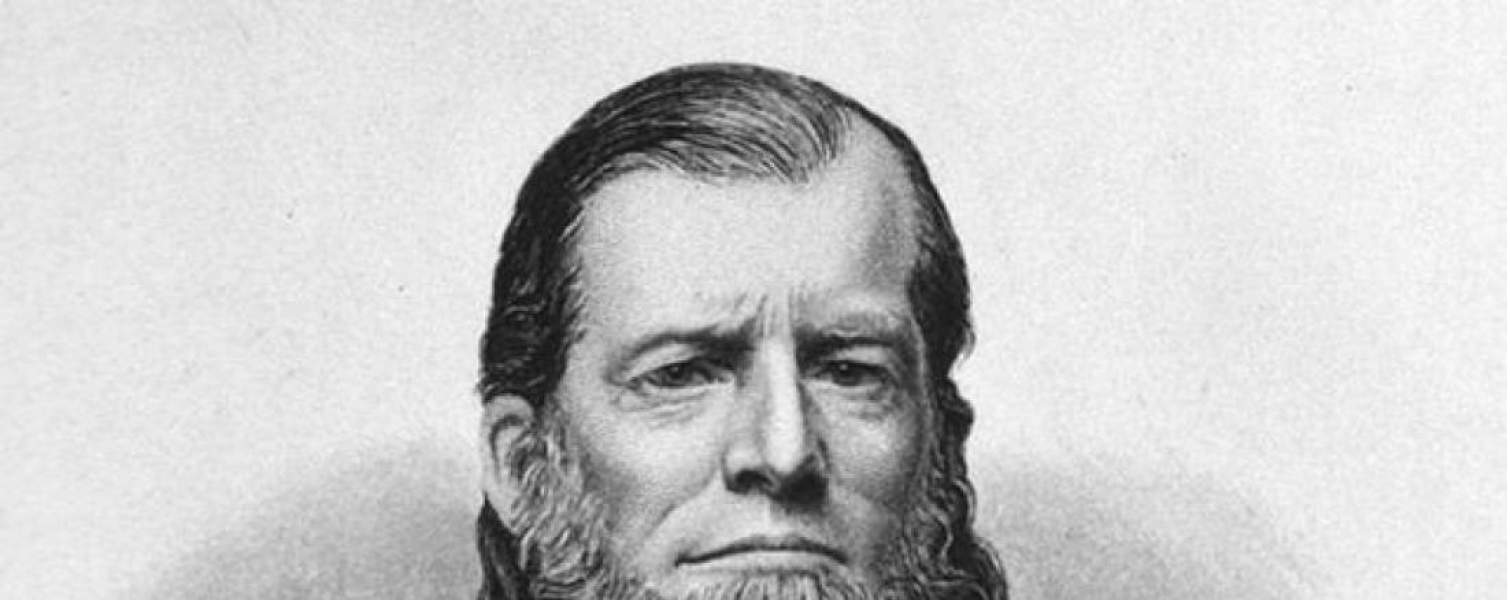

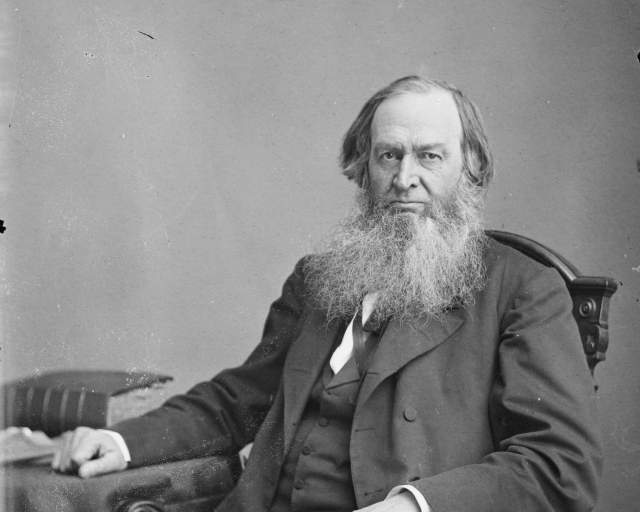

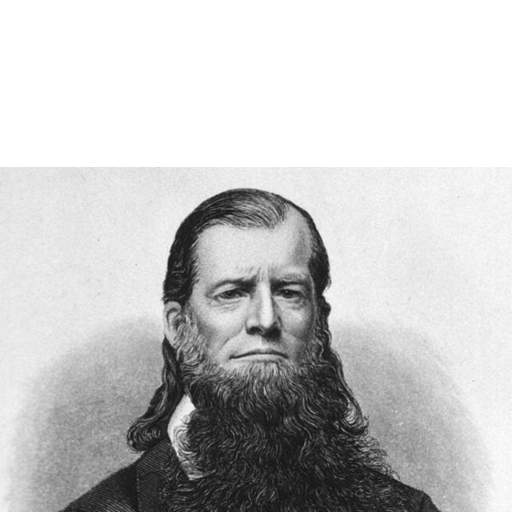

James Caleb Jackson’s views on religion are little known, but he played significant roles in the abolition and dress reform movements. Less laudably, he passed the second half of his life as a colorful and highly successful practitioner of quack medicine.

Jackson was born in Manlius, New York, on March 28, 1811. His father was James Jackson, a physician and surgeon who served in the War of 1812. Torn between his father’s insistence that he pursue a medical career and that of his mother, Mary Ann Elderkin Jackson, that he become a missionary, young Jackson rejected both options and resolved to earn his living by farming. At the same time he became a committed campaigner for temperance and abolition. Originally a Democrat, he voted to reelect Andrew Jackson in 1832 but soon after quit the party because he thought it too friendly toward slavery.

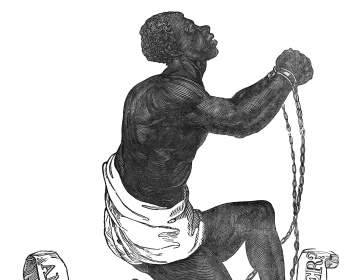

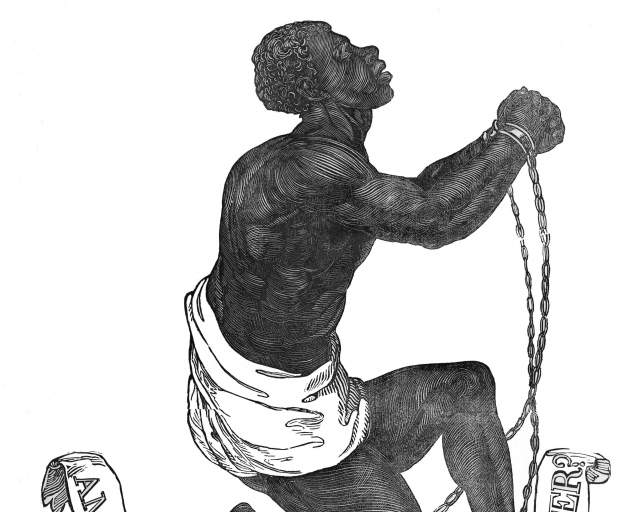

Abolitionist. Jackson attended the first meeting to reorganize the New York Antislavery Society, which began on October 21, 1835, at Utica's Second Presbyterian Church. When a hostile mob broke up that meeting, one of the other attendees, millionaire philanthropist Gerrit Smith, invited delegates to reconvene the next day at a property he controlled in his native Peterboro. The meeting successfully concluded on October 22.

Jackson attended an annual meeting of the Oswego County Anti-slavery Society at "the Presbyterian church in New Haven," now the First Congregational Church of New Haven, on January 17, 1839. He lectured around the region for the New York State Anti-Slavery Society during 1839, and served on the Society's executive committee (1840–1841). From 1840–1842 he was a corresponding secretary of the American Anti-Slavery Society and an associate editor of the New York City-based newspaper, The National Anti-Slavery Standard. On August 21-22, 1850, he attended a famous convention in opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law held on two sites in Cazenovia.

Initially Jackson opposed the Liberty Party, a single-issue antislavery party championed by abolitionist and philanthropist Gerrit Smith. Jackson thought abolition was better pursued through the established national parties. In 1841, Smith persuaded him otherwise. Jackson became a Liberty Party spokesperson and edited two Party papers: the Smith-funded Madison County Abolitionist, based in Cazenovia, and Utica’s Liberty Press. In 1844 Jackson purchased an Albany anti-slavery paper, The Albany Patriot, and edited it for three years.

Quack Physician. By 1847 Jackson's health was failing. (The Albany Patriot ceased publication in 1848.) Much medicine of the time was scientifically dubious; as it happened, Jackson experienced some relief from hydrotherapy, a quack system stressing water-based treatments. After regaining his health, Jackson began a new career as a hydropathic practitioner.

Unhampered by his lack of medical credentials, Jackson helmed a hydropathic sanatorium in Skaneateles starting in 1847. Belatedly, he earned a medical degree from Central Medical College in Syracuse in 1850. In 1858, he took over operation of the Dansville (New York) Water Cure Facility. Jackson renamed the struggling hydropathic spa Our Home on the Hillside. Under Jackson's leadership it achieved national prominence, treating thousands of patients annually (among them, nursing pioneer and future American Red Cross founder Clara Barton).

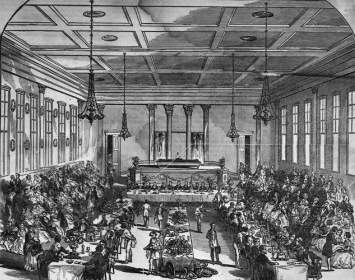

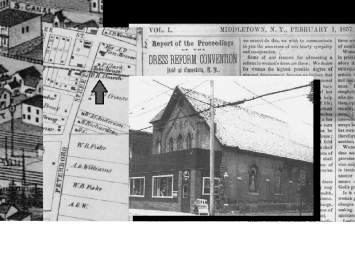

Dress Reformer. In the mid-1850s Jackson embraced the dress reform movement, giving it new life after suffrage activists had largely abandoned the so-called Bloomer costume, finding it unproductively controversial. In February 1856 Jackson founded the National Dress Reform Association (NDRA) to promote healthier and more practical clothing for women. Controversially, he claimed to have invented the “pantaloons reform dress”—a mid-calf skirt over pantaloons—at his sanatorium, as early as 1849. If true, he would have invented “Bloomers” two years before suffragist Elizabeth Smith Miller is generally credited with creating the style. This seems never to have strained Jackson’s relationship with Gerrit Smith—Miller’s father—for Smith attended and helped to finance the first NDRA convention, held at Canastota on January 7–8, 1857. Jackson presided at that event and at annual conventions through 1861. The NDRA met irregularly during the Civil War. Its first postwar convention, held on June 21, 1865, at Rochester's Corinthian Hall, foundered amid factional conflict; the organization failed shortly thereafter.

Cereal Innovator. Jackson maintained his hydropathy practice while cultivating an obsession with pure foods. He had created the first dry breakfast cereal, called Granula, in 1863. In 1878 John Harvey Kellogg, proprietor of another scientifically dubious sanatorium in Battle Creek, Michigan, visited Our Home on the Hillside. A few years later Kellogg developed his own dry cereal, which he also called Granula. Jackson sued successfully; Kellogg had to change the name, coining the word Granola. (Kellogg’s product little resembled the granola of today; instead, it was the forerunner of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes.)

In 1879 infirmity compelled Jackson to hand off management of his sanatorium to his son, James H. Jackson. He retired to North Adams, Massachusetts, in 1886, maintaining his involvement in Republican politics. On one of several visits to Dansville, Jackson took sick and died there on July 11, 1895, aged eighty-five. He was buried in Dansville’s Green Mount Cemetery. Our Home on the Hillside went bankrupt in 1914; through various reorganizations, the facility continued to operate until 1971. Some abandoned buildings remain on the site.

James Caleb Jackson

James Caleb Jackson (1811 – 1895)

Associated Historical Events

First New York State Antislavery Meeting

October 21–22, 1835

Oswego County Anti-Slavery Society Annual Meeting

January 17, 1839

New York State Convention of the Liberty League and National Reform Party

September 28, 1848

Fugitive Slave Law Convention at Cazenovia

August 21–22, 1850

National Liberty Convention

September 30, 1852

First Annual Meeting of the NDRA

June 18 - 19, 1856

First National Dress Reform Association Convention

January 7–8, 1857

Final National Dress Reform Association Convention

June 21, 1865