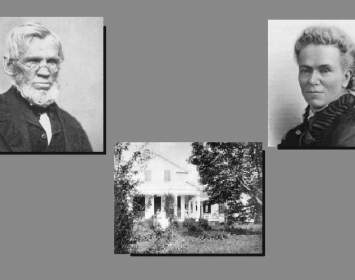

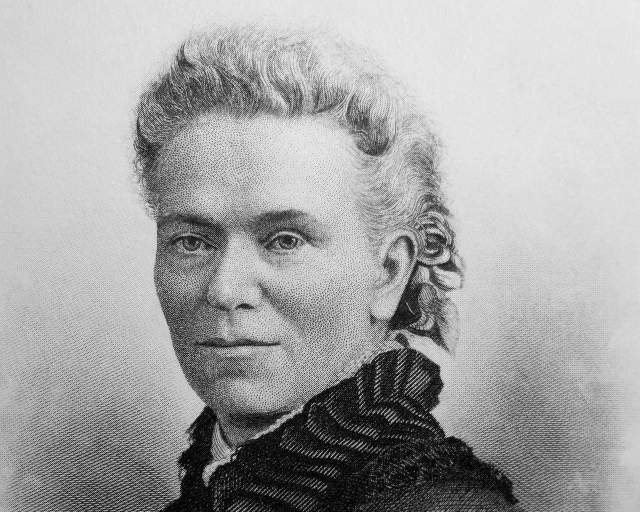

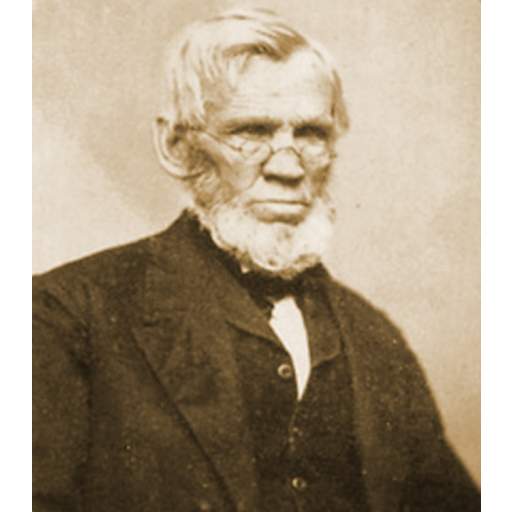

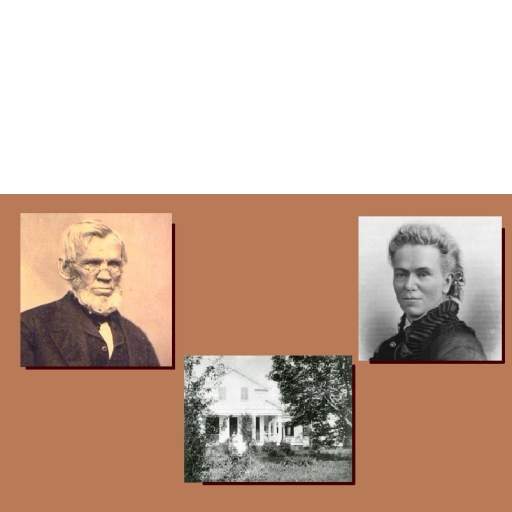

Hezekiah Joslyn (1757–1865) was a physician, a nationally known abolitionist, and the father of woman’s rights leader Matilda Joslyn Gage. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) Matilda's leadership abilities in part reflected Joslyn's unusual approach to her upbringing. (Depicted are Joslyn; his Cicero home; and Matilda Joslyn Gage, born in that home.)

Dr. Joslyn arrived in Cicero in 1823, where he purchased a retiring doctor’s practice. Two years later, he married Helen Leslie, an accomplished amateur musician. They established an elegant household on a site along what is now Brewerton Road; among other fine trappings, the Joslyn home boasted an English piano, one of the first such instruments in Onondaga County. The couple welcomed their daughter Matilda Electa Joslyn in 1826. Joslyn was prominent in the community and was twice elected a Town of Cicero supervisor.

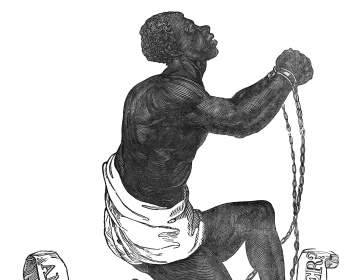

A staunch abolitionist, Joslyn made his home a station on the Underground Railroad. Among his associates in this work were Gerrit Smith; the mercurial John Anderson Collins, who would soon abandon abolitionism to found an ill-fated utopian community at Skaneateles; and Alexander Campbell, who would found the Campbellites, a forerunner of the Seventh-day Adventists. Joslyn was a founder of the Liberty Party, which advocated abolition and temperance; he (unsuccessfully) ran for Congress on its ticket in 1844.

In May 1843, Joslyn joined a small committee to evaluate applicants seeking to purchase shares in the Skaneateles Community, a freethinking Fourierist utopian project Collins was establishing outside Skaneateles. Joslyn planned to join the Community; on October 14 he, his wife, and eighteen-year-old Matilda attended a convention on its grounds that marked the formal commencement of its operation. Among the speakers was the nationally prominent feminist and freethinker Ernestine L. Rose. Joslyn changed his mind and abandoned the Skaneateles Community about a month later, after Collins published a radical statement requiring Community members to embrace a set of principles including atheism, anarchism, free love, and the rejection of private property. The Community project collapsed after less than three years.

Joslyn was known for defending his views zealously. Writing after his death, an acquaintance known only as H. P. S. would recall him as “a radical of the most rebid [sic] type, a red-hot temperance advocate and anti-slavery champion. ... If a remark was made that was contrary to his beliefs, woe to the person who made it ... Dr. Joslyn would be upon him with a rattling vocabulary of argument that would leave the heedless author of the first remark floundering in the dust. This manner of speech and argument was transmitted in great measure to his daughter, Mrs. Gage.”

Indeed, Joslyn raised his daughter in a most novel way. He taught her physiology and anatomy, among other subjects. Even as a young girl, she would ride alongside him on his medical rounds to outlying communities. When she was older he attempted unsuccessfully to secure her admission to a medical school. Matilda Joslyn Gage later wrote of her father’s tutelage: “If there has been one education of more value to me than all others, it was the training I received from my father to think for myself.... this one early lesson of examining all questions for myself has been of infinitely more value to me than all the classics and sciences of the world would have been without free thought.”

By 1850, Joslyn had left Cicero to set up a new medical practice in Syracuse. His whereabouts thereafter are not known, with the exception that on February 16, 1850, Joslyn traveled to Auburn, New York. There he tested Sarah Tamblin, a supposed psychic medium who produced percussive sounds—so-called “spirit rappings”—common among early adopters of Spiritualism. Joslyn tied up the medium so that she could not move, or so he thought, and was baffled when she continued to produce the “rapping” sounds. (The next year three investigators from the University of Buffalo would demonstrate that such “rappings” were produced by cracking bone joints in the lower extremities; they proved this by placing the Fox sisters—who had launched the “rapping” craze—on sofas with pillows under their feet, rendering them unable to produce the sounds. This was a stratagem Joslyn had not attempted with Mrs. Tamblin.)

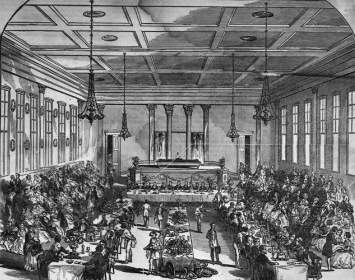

On February 13–14, 1857, Joslyn was in Rochester, serving as vice-president of an anti-slavery convention at Corinthian Hall. Speakers included William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and Susan B. Anthony.

Joslyn died on October 30, 1865, at the Fayetteville home of his daughter Matilda. He was buried in Cicero, in a hillside graveyard less than a thousand feet from the site of his Cicero home. His imposing grave marker was inscribed: “AN EARLY ABOLITIONIST.” Among all his achievements, that was the one of which Hezekiah Joslyn was most proud.

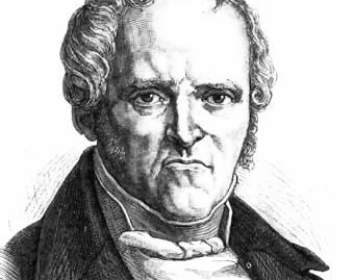

Hezekiah Joslyn

Hezekiah Joslyn. Image courtesy of Matilda Joslyn Gage Center.

Hezekiah and his daughter

Hezekiah Joslyn, his Cicero residence, and his daughter Matilda (Joslyn Gage), who was born there.

Associated Historical Events

Rochester Antislavery Convention

February 13–14, 1857

Death of Hezekiah Joslyn

October 30, 1865