Charles De Berard Mills (C. D. B. Mills, 1821–1900) was a prominent figure in the abolition and, later, freethought movements. He was born in New Hartford, New York, to Abram Mills and his wife, Grace De Berard Mills. Abram Mills was himself an ardent abolitionist, an early graduate of the Oneida Institute in Whitesboro, a Presbyterian manual labor college founded in 1827 that had religiously liberal leanings. (In a manual labor college, students paid their way by contributing labor to business activities that funded college operations.) Young Charles Mills attended the Oneida Institute as his father had; by that time, the Institute was led by abolitionist firebrand Beriah Green, who accepted a large number of African American students and held classes for black and white students together, making the Oneida Institute America’s first racially integrated institution of higher education. Presumably Mills belonged to one of the Institute’s final graduating classes; Green was discharged and the Oneida Institute was sold to a Free Will Baptist group in 1844.

Mills arrived in Syracuse in the early 1840s. He met his future wife, Harriet Ann Smith, when he was engaged to educate her privately by her father, a wealthy farmer named David Smith. Charles and Harriet married on July 9, 1845. They resided first in Smyrna, New York, and then Elyria, Ohio. He worked variously as a teacher and a minister, each time losing those positions because of his controversial abolitionist views. While at Elyria, he taught at Western Reserve College, an early center of abolitionist activism, but even there Mills’s stance was considered extreme. He was offered a professorship, but declined because if he were appointed, he knew he would be expected to temper his views.

Charles and Harriet returned to Syracuse in 1851. Charles, or C. D. B. as he preferred to be known, had chosen Syracuse because he hoped to meet the Rev. Samuel Joseph May, a prominent abolition leader in the city; in this he was successful. (After his death in 1871, May would be remembered by the 1885 May Memorial Church, home to a liberal Unitarian congregation.) Mills took a job as bookkeeper for a plant nursery, a job in which his nights and weekends would be his own in which to study and write. He began to earn additional income as a writer and lecturer on abolition and other reform topics.

The choice of Syracuse turned out to be propitious; days after the Millses arrived in Syracuse, the rescue by abolitionists of an escaped slave nicknamed "Jerry" from federal custody made the city briefly the center of the abolitionist universe. Later in her life, Harriet Smith Mills recalled a celebration of the Jerry Rescue, featuring as speakers Gerrit Smith and Lucretia Mott, as the first event of consequence she remembered after moving to Syracuse.

In 1857, the Millses built a fine house at what is now 1074 West Genesee Street. It became a salon of sorts, a ready gathering place for prominent woman’s rights activists, abolitionists, and temperance advocates. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) Visitors and house guests of national stature included Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, Mott, Carrie Chapman Catt, William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Amos Bronson Alcott, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The house still stands, was recently restored, and now serves as a halfway house for recovering addicts.

At some point during this period, Mills served as minister to the strongly Abolitionist Free Church of Canastota, where he succeeded his mentor, Beriah Green, who had succeeded the church’s founder in 1854 and served for an indeterminate period.

In 1876, Mills published the first sympathetic book-length treatment of Buddhism released in the United States. Among his other published works was the book The Tree of Mythology, Its Growth and Fruitage: Genesis of the Nursery Tale, Saws of Folklore, Etc. (1888).

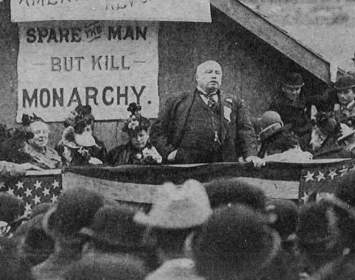

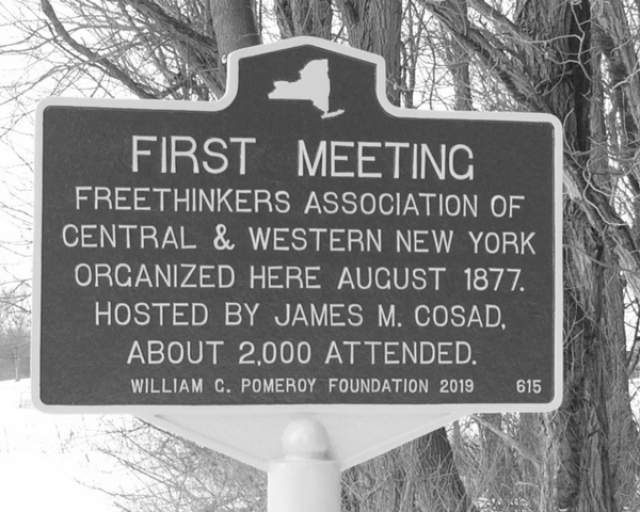

Despite his clerical service, Mills’s years of independent study into religious matters led him to abandon his beliefs in the sacred. He emerged as a freethinker, becoming active in the New York Freethinkers Association, and helped to administer its nationally-important conference held at Watkins Glen in 1878. He had also attended and spoken at its predecessor event, the Grove Meeting held at Huron, New York, in 1877.

His freethought activism did not interfere with his becoming a highly respected member of community in Syracuse. For fourteen years, he served as general secretary of that city’s Bureau of Labor and Charities and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Despite these achievements, Mills is best remembered today because of his daughter, Harriet May Mills (born 1857). Her middle name was a tribute to Samuel J. May. In adulthood, Harriet May Mills worked toward the cause of woman's suffrage. In 1897, while a committee head of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association (NYSWSA), she recruited Geneva-based suffrage activist Elizabeth Smith Miller to organize a NYSWSA's twenty-ninth annual conference held at the Smith Opera House, Collins Music Hall, and the Nester Hotel in that city. In 1892 she helped organize the 24th annual NYSWSA Convention. Plenary sessions were held at Syracuse's Wieting Opera House; C. D. B. Mills took part in a panel discussion on suffrage issues that included both male and female speakers. Early in the twentieth century, the Mills home became the headquarters of NYSWSA. By 1920, Harriet would campaign for election as Attorney General of the State of New York in 1920, becoming the first female to seek a major state-wide office as a candidate of a major political party. By this time, Harriet’s fame had far eclipsed her father’s.

C. D. B. Mills died of old age on May 15, 1900. He was 90 years old. His body was cremated, then a provocative act frowned upon by Christians. His ashes were returned to his birthplace, New Hartford, where they appear to have been misplaced and never interred in the family vault.

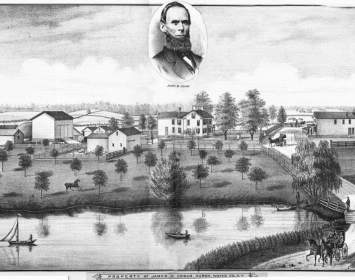

C. D. B. Mills in midlife

Rare image of C. D. B. Mills in midlife, digitally enhanced.

Mr. and Mrs. C.D.B. Mills

Courtesy Beth Crawford.

A youthful C. D. B. Mills with his wife, Harriet Ann Mills. Courtesy of Beth Crawford.