Frederick Douglass Sites

Custom

145.0 Miles

This trail extends from Rochester on the west to Peterboro on the east. Some sites in Rochester are unmarked, but most contain a gravestone, public artwork, historic structure, or museum. The Susan B. Anthony House in Rochester and the sites in Seneca Falls and Peterboro house mid-sized museums; allow ample visit time. Visitors seeking a shorter curated experience might wish to visit only the Rochester-area sites.

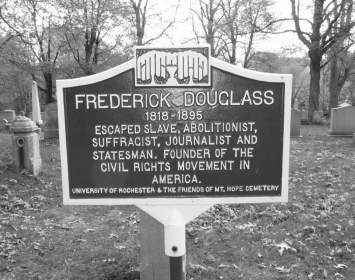

Iconic anti-slavery campaigner Frederick Douglass spent the most productive twenty-five years of his life in Rochester. The area is rich with sites that help tell his story, including his imposing grave site.

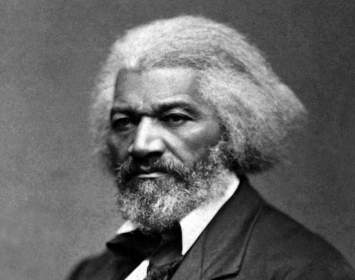

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), an escaped slave, became one of the most charismatic and forceful leaders of the American abolition movement. In Rochester, he excelled as an orator and as the editor of the newspaper The North Star and other renowned anti-slavery publications.

Born into slavery on a Maryland farm, Frederick nonetheless learned to read in childhood. As a young man he briefly embraced Christianity but soon abandoned it, observing that the religion did so little to soften the behavior of slave owners. At the age of twenty he made his daring escape. (In later life, he would remark that “Praying for freedom never did me any good til I started praying with my feet.”) He adopted the colorful surname “Douglass” from a character in a book by Sir Walter Scott. He was soon a popular speaker at abolition meetings.

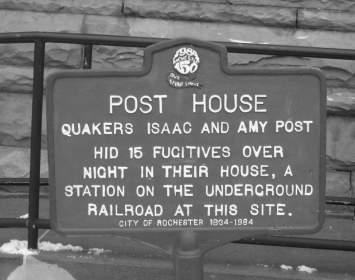

In 1847, Douglass came to Rochester, then a hotbed of reform activism. He built warm friendships with Rochester abolitionists, including the radical Quakers Isaac and Amy Post, and the famed abolitionist and feminist activist Susan B. Anthony.

In July 1848, Douglass and Amy Post traveled to Seneca Falls, New York, where they attended the Woman’s Rights Convention that sparked the nineteenth-century woman's suffrage movement (nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's). He was the only male to speak at the convention, drawing parallels between black men and American women as equally disenfranchised. The site of this historic convention has been restored. In the museum there, an assemblage of life-size statues of conference participants includes an excellent likeness of Douglass.

Douglass was also a close associate of millionaire abolitionist Gerrit Smith, who generously supported abolition activism and the Underground Railroad from his estate in Peterboro, New York. In August 1850, Douglass and Smith attended a convention in Cazenovia held to protest the Fugitive Slave Act. Both appear in a Daguerreotype photo which went on to become a classic image of Northern abolitionist leaders.

Douglass was active with the Underground Railroad. At one point in 1851, he sheltered a party of eleven fugitives led by Sojourner Truth.

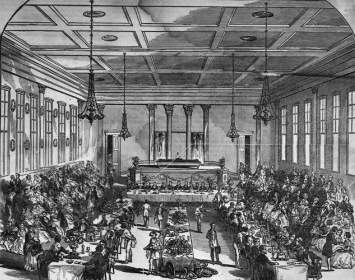

Angered by passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, Douglass delivered his famous “Fifth of July” address on July 5, 1852, at Rochester’s Corinthian Hall. In thunderous language he condemned America’s July Fourth holiday because there was neither dignity nor freedom for Americans whose skin was black. He reserved some of his harshest language for pro-slavery Christian clergymen: "I would say welcome infidelity! Welcome atheism! Welcome anything! In preference to the gospel as preached by those divines! They convert the very name of religion into a barbarous cruelty." Many historians consider this the most important anti-slavery speech of the years leading up to the Civil War. Sadly, its site is now a city parking structure.

Douglass was a good friend of the agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll. Douglass once remarked that Ingersoll and Abraham Lincoln were the only white men in whose company "he could be without feeling he was regarded as inferior to them."

Douglass owned two homes in Rochester—one close to downtown, its site unmarked, the other outside the city limits (though well inside them today). The latter site contains a highly informative historical marker. During and after the Civil War, Douglass became a figure of international stature and spent much of his time in Washington, D.C. In 1872, he and his family moved permanently to the nation’s capital after a suspicious fire destroyed their home in rural Rochester.

Douglass died in Washington, D.C., on February 20, 1895. Following funeral services there, his remains were brought to Rochester where on February 26 a solemn memorial service was held at the city’s Central Church. A large delegation accompanied his body to Mount Hope Cemetery, where his grave site is now a principal attraction. A statue of Douglass by sculptor Sidney W. Edwards was installed before the city’s train station in 1899; in 1941, it was moved to a location overlooking the Highland Park Bowl, where it stands today.