Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) was one of the three foremost leaders of the National Woman Suffrage Association, the radical wing of the nineteenth century woman suffrage movement. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman or woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women or women's). The other top leaders were Susan B. Anthony of Rochester and Matilda Joslyn Gage of Fayetteville.

Stanton was a principal organizer of the first Woman’s Rights Conference held at Seneca Falls, where she resided, in 1848.

Stanton was a cousin of the prominent abolitionist and woman’s rights activist, the millionaire philanthropist Gerrit Smith of Peterboro. As a child, Elizabeth Cady met an escaping fugitive slave at Smith's estate; as a young woman, Stanton met her husband, the professional abolitionist Henry Brewster Stanton, at a social event held there.

Early Life. Elizabeth Cady was born to two strict Calvinists: the U.S. Congressman and New York jurist Daniel Cady and his patrician wife, Margaret Livingston. Cady was an ardent abolitionist. No Cady son survived; the eldest, Eleazar, died during his final year of college. As a result, Elizabeth Cady became the vehicle for Daniel Cady's dreams of carrying on family traditions. She promised her father "to be all my brother was." Early on, the Cady father educated his five girls, Elizabeth especially, as if they were boys. But he would not send her to college; instead he compelled her to attend Emma Willard's Troy Female Seminary, a rigorous finishing school. She acquired further informal education on long visits to the Gerrit Smith estate. (Elizabeth Cady's unconventional upbringing resembled the even more radical childhoods of Matilda Joslyn, later Matilda Joslyn Gage, and of radical dress reform activist Mary Edwards Walker.)

Whatever Elizabeth's attainments, they were never enough for Daniel Cady, who repeatedly told her "You should have been a boy."

An avid Christian, in adolescence Elizabeth Cady was influenced by the teaching of evangelist Charles Grandison Finney. In her later autobiography, she would describe her religious upbringing as more painful than anything she experienced as an adult. Yet if her father was devout, he was also educated and a rationalist in matters such as legal discourse, and he educated his daughters accordingly.

Cady would later credit Gerrit Smith with encouraging her to overcome dogmatism, advancing, as Smith had, "from the uncertain ground of superstition and speculation to the solid foundation of science and reason."

Cady married Henry Stanton in 1840. It was a nontraditional ceremony from which the word "obey" had been removed.

The Stantons named their third child (born 1845) Gerrit Smith Stanton in tribute to the abolitionist philanthropist and Elizabeth's cousin.

Stanton's wide-ranging interests in social reform were evident in a letter she wrote to the Third National Woman’s Rights Convention, held on September 8–10, 1852, in Syracuse's City Hall. She expressed her regrets at being unable to attend and, among other points, made a plea for co-education: "Does not sound philosophy and long experience teach us that man and woman should be educated together?" The letter was read aloud to the convention delegates.

Emerging as a Freethinker. By age forty, Stanton was becoming a freethinker in matters of religion. In 1855, Stanton wrote in a letter to Elizabeth Smith Miller, daughter of Gerrit Smith, that since The New York Observer had labeled her an infidel, “I ought to look up my associates,” Thomas Paine and Fanny Wright—which she did.

Who Should Get the Vote? Following the Civil War, reformers acrimoniously debated whether African Americans or women should get the vote first. Stanton believed women should not delay their pursuit of the vote because of a popular conviction that "this is the negro's hour." If black men were enfranchised before women, she urged that women demand their right to vote at once, writing in 1866 that they should "press in the constitutional door the moment it is open for the admission of Sambo." This was one of several occasions when Stanton used disparaging racial language. In 1867, she predicted that black male enfranchisement would harm the country as "2,000,000 ignorant men," whom she just previously described as "the lowest strata of manhood," "are ushered into the halls of legislation."

Stanton's concern that African Americans would secure the franchise before women did was borne out in 1868 with the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution, which guaranteed citizenship (and the vote) to all males regardless of race. This was the first time the word male was included in the Constitution. "Woman's cause is in deep water," Stanton wrote to Anthony.

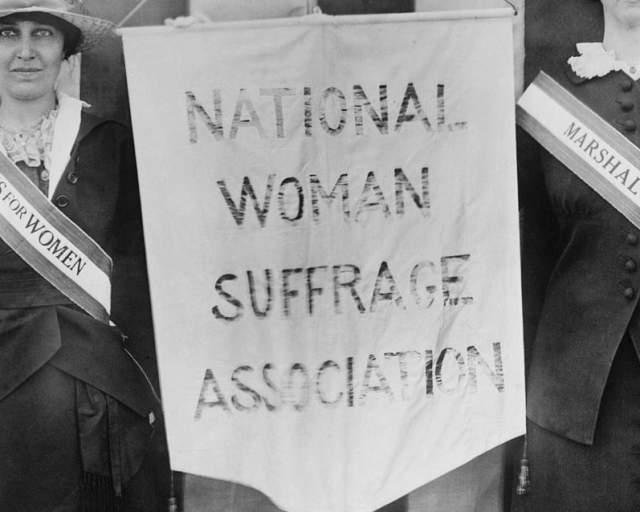

A Split in the Suffrage Movement. In 1869, a split occurred between more- and less-socially radical suffrage activists. Stanton, Anthony, and Gage jointly led the more radical faction, forming the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) with heavy support in the state of New York. The NWSA sought a Constitutional amendment establishing woman's right to vote along with a roster of other advances, such as clearer property rights for married women. New Englanders Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, and others led the more moderate American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which sought to win woman's suffrage state by state and came to focus very narrowly on winning the vote. As historians Susan Goodier and Karen Pastorello expressed it in their book Women Will Vote (Ithaca, N.Y.: Three Hills Press, 2017), "the split in ideology between those who supported black men’s rights and those who sought universal rights fractured the women’s movement for more than two decades. And, with the greater national focus on voting rights, women’s rights activists shifted their focus to the singular demand for woman suffrage."

Stanton, Anthony, and Gage began work on The History of Woman Suffrage in 1876. The first volume was published in 1881. Stanton presented a copy to the Cornell University Library in Ithaca, paying tribute to that institution's nondenominational, if not outright freethinking, orientation. (For more on the controversies surrounding Cornell's religious neutrality, see the profile of university co-founder Andrew Dickson White.) The third volume of The History, the final volume Stanton, Anthony, and Gage would edit together, was published in 1886.

A Cruel Merger.

In 1890, Susan B. Anthony reached out to Lucy Stone to heal the rift between NWSA and AWSA. In 1890, though not without controversy, the two groups merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Radicals such as Stanton and Gage were sidelined from real leadership. However, Stanton was prevailed upon to accept a figurehead presidency of NAWSA from 1890 to 1892. This precipitated a break with Gage, who had counseled Stanton to stand firm in resisting Anthony's more conservative recent veerings.

Yet the old ties would not be denied. The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 included the World's Parliament of Religions. Stanton could not attend, so Anthony delivered her speech "The Worship of God in Man," which denounced church and state for oppressing the vulnerable and called for a "religion of humanity" centered on "Justice, Liberty, Equality for all the children of the earth."

Stanton, the Public Freethinker. Only late in her career did Stanton go fully public with her freethought, excoriating Christianity for its oppression of women in The Woman’s Bible (1895–1898), which she wrote at the head of a committee including twenty-six other notable women. It became a best-seller, much to the displeasure of suffragists including Anthony, who wished to distance the suffrage movement from any antireligious stance.

The Woman’s Bible has been recognized as an American Treasure by the U.S. Library of Congress.

At the 1896 convention of NAWSA (following publication of the first volume of The Woman's Bible), Stanton's book was formally repudiated. The action was engineered by younger suffragists Rachel Foster Avery and Carrie Chapman Catt, over the objections of Clara Bewick Colby and Lillie Devereux Blake—and much to the quiet dismay of Anthony. Stanton wrote critically of this action in the second volume of The Woman's Bible (1898).

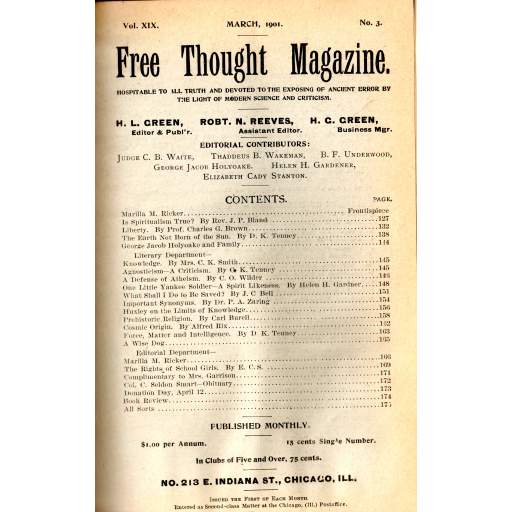

Sidelined to the Freethought Movement. So controversial did Stanton become that from 1898 until her death in 1902, Stanton could seldom get her writings published in suffrage publications. Instead she became a regular columnist for Free Thought Magazine, an atheist periodical edited by H. L. Green to which she had been an occasional contributor throughout the 1890s.

The agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll was a close friend, and she took his death in 1899 very hard. "No other loss, outside my own family, could have filled me with more sorrow," she wrote in her diary.

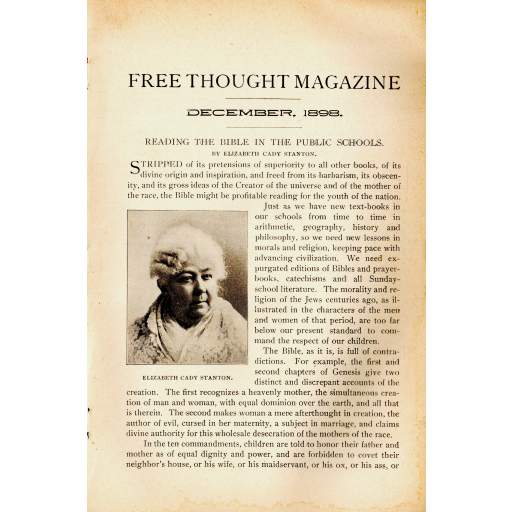

Stanton was a radical of many causes, among which freethought may have meant even more to her than suffrage. Her last published letter was an October 26, 1902, letter to the editor of The New York Evening Post, calling for the removal of Bibles from public schools. She would die but sixteen days later.

Among principal leaders in the suffrage movement, only Matilda Joslyn Gage had a longer record as a critic of religion.

Revealing Treatment. History’s treatment of Anthony, Stanton, and Gage is most revealing. Early twentieth-century suffragists tended to look back on Anthony, a closet freethinker who sought to keep Christian groups in the suffrage movement, as its sole founding leader. Stanton, who revealed her infidel views late in life after having already established a towering reputation as a suffragist, was almost forgotten until her rediscovery by second-wave feminists of the 1960s. (Her home in Seneca Falls has been painstakingly restored by the National Park Service as part of its Women's Rights National Historical Park at Seneca Falls.) Gage, who had been critical of religion throughout her suffrage career, was largely forgotten by history until the 1990s, when her memory was rehabilitated largely through the efforts of feminist scholar Sally Roesch Wagner, now director of the Matilda Joslyn Gage Center.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902)

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902).

Free Thought Magazine masthead

Masthead of March 1901 issue of Free Thought Magazine, a national periodical published from Chicago by freethinker H. L. Green, includes Stanton among the Editorial Contributors.

Stanton Article in Free Thought Magazine

First page of a December 1898 article by Stanton in Free Thought Magazine. At this time, Stanton was largely unable to publish in the suffrage press because of her radical religious views.

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls

July 19–20, 1848

Follow-On Woman's Rights Convention

August 2, 1848

Third National Woman’s Rights Convention

September 8–10, 1852

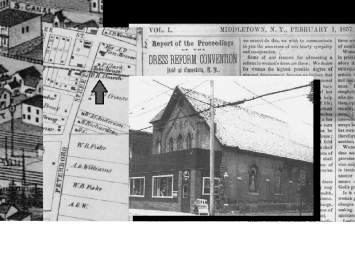

First National Dress Reform Association Convention

January 7–8, 1857

1878 Woman's Rights Convention

July 19, 1878

Twenty-Second NY State Suffrage Convention

December 16–18, 1890

Twenty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 12–16, 1894

Twenty-Ninth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 3–6, 1897