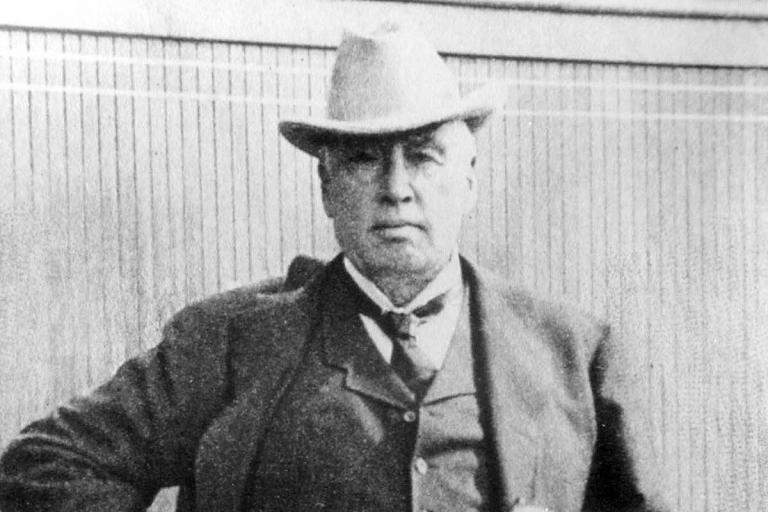

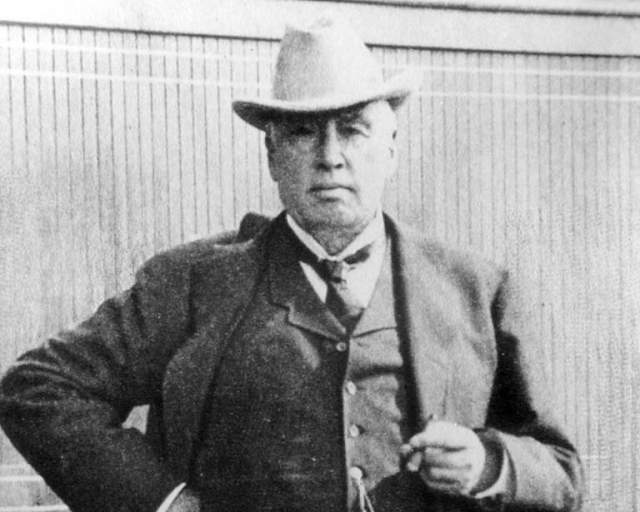

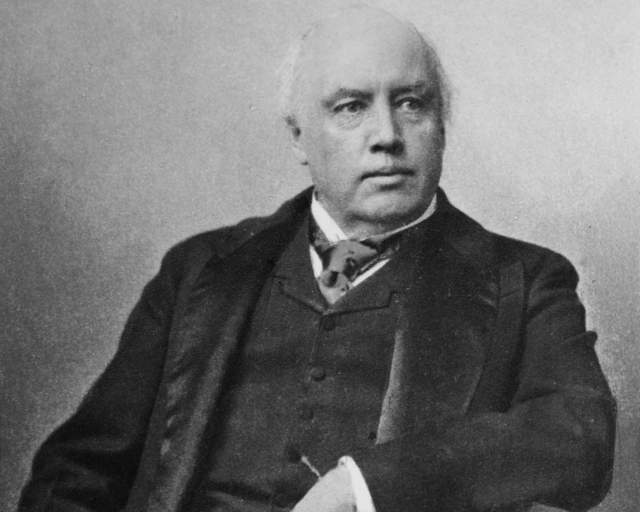

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833–1899) is too little known today. Yet he was the foremost orator and political speechmaker of late nineteenth-century America—perhaps the best-known American of the post-Civil War era. On tour after tour, he crisscrossed the country and spoke before packed houses on topics ranging from Shakespeare to Reconstruction, from science to religion. Known as the Great Agnostic, Ingersoll was the best-known and most widely respected ambassador the American freethought movement would ever have.

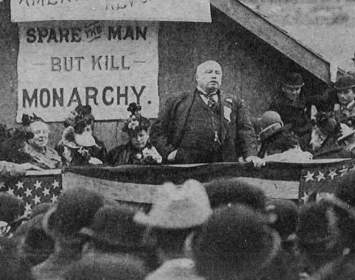

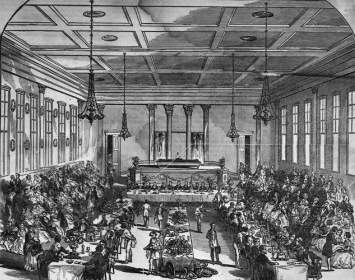

In an age when oratory was the dominant form of public information and entertainment, Ingersoll was the unchallenged dean of American orators. He was seen and heard by more Americans than would see or hear any other human being until the advent of radio and motion pictures.

Ingersoll bitterly opposed the religious Right of his day—yet though he was an outspoken agnostic, he was also the foremost political speechmaker of the Republican Party. During Ingersoll’s public life, no GOP candidate for whom he declined to campaign attained the White House.

Ingersoll was a good friend of iconic antislavery campaigner Frederick Douglass. Douglass once remarked that Ingersoll and Abraham Lincoln were the only white men in whose company "he could be without feeling he was regarded as inferior to them." In a September 1876 speech hailed as one of the foremost literary responses to the Civil War, Ingersoll delivered a searing indictment of slavery that could have been uttered yesterday: "Four million bodies in chains -- four million souls in fetters. All the sacred relations of wife, mother, father, and child trampled beneath the brutal feet of might. And all this was done under our own beautiful banner of the free."

Early Life. Ingersoll was born on August 11, 1833, in Dresden, New York. His father, the Rev. John Ingersoll, was a poor minister who moved from church to church. He was also an abolitionist, a friend and fellow activist of the Rev. Beriah Green, who almost certainly passed through Dresden and visited the Ingersolls as he traveled east from Ohio to assume the presidency of the Oneida Institute, a radical boarding school that educated Black and White students together. Green would have visited the Ingersolls shortly before Robert's birth. Robert Green Ingersoll's middle name was a tribute to Beriah Green.

Rev. Ingersoll's abolitionism (unusual for the time, even in the North) and his relentless preaching about hellfire wore out yet another congregation's welcome: The Ingersolls left Dresden less than four months after Robert's birth. Ingersoll's mother died in Cazenovia, New York, when Robert was but three years old. His father held various preaching appointments from New York City to the Midwest. The family's travels ended after several years in Peoria, Illinois.

Robert Ingersoll first attained regional prominence in Peoria. There he and his brother, Ebon Clark Ingersoll, had a thriving legal practice.

Robert first entered politics as a Democrat in the mold of Lincoln debate opponent Stephen Douglas, though probably the most strongly abolitionist Douglas Democrat Illinoisans had ever seen. “Ingersoll was a Democrat until the attack upon Fort Sumter," noted his biographer Herman E. Kittredge, "and a Republican thence to the day of his death.”

At the outbreak of the Civil War Robert raised a cavalry regiment at Peoria. He commanded it with the rank of Colonel, and was known ever since as Colonel Ingersoll or, more casually, "Colonel Bob."

He gained national attention with his bombastic speech nominating James G. Blaine for the Republican presidential nomination in 1876. The next year he moved to Washington, D. C. In 1885, already a prominent national figure, he relocated to New York City.

Ingersoll and Freethought. At various times, Ingersoll held high offices in most of the major American freethought groups of the time, including the National Liberal League. When atheist publisher D. M. Bennett was arrested at an 1878 freethinkers’ conference in Watkins, now Watkins Glen, for selling a birth control and marriage reform tract some deemed obscene, Ingersoll—who had not attended the conference—offered his legal services and personally appealed to President Rutherford B. Hayes to drop the charges. (For details of this incident, click here.)

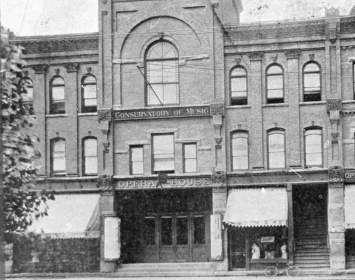

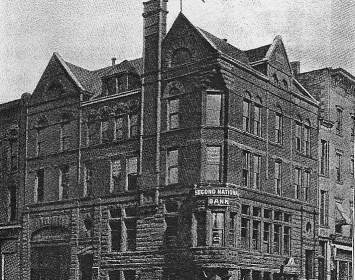

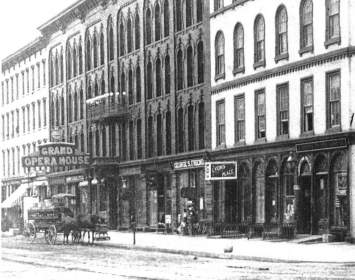

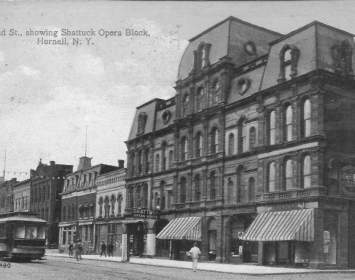

Ingersoll was among the speakers when the sponsor of the Watkins conference, the New York Freethinkers Association, convened in Hornellsville for its fourth annual convention on September 2–6, 1880.

In 1887, Ingersoll defended Rochester-based minister-turned-freethinker Charles B. Reynolds, who had been arrested on blasphemy charges in New Jersey. The entire defense consisted of Ingersoll’s summation, which was delivered from memory and lasted several hours. Reynolds was found guilty, but given only a token fine. Ingersoll paid the fine himself and charged Reynolds nothing for his services. Though his client was convicted, Ingersoll succeeded in his larger agenda: no American state or municipality would take a defendant to trial on a charge of blasphemy again, save for Maine’s successful 1919 prosecution of Lithuanian freethinker Michael X. Mockus.

In 1888, a letter from a fervently Christian attorney (Hiram L. Suydam) of Geneva elicited what may be Ingersoll's most vituperous condemnation of Christianity. He closed his letter of reply dated September 29 with these words: "...at least one hundred and fifty millions of human beings have been sacrificed to establish what is called the Christian religion. I am opposed to the whole business. I want to get rid of the old religions, and I want no new ones in their place."

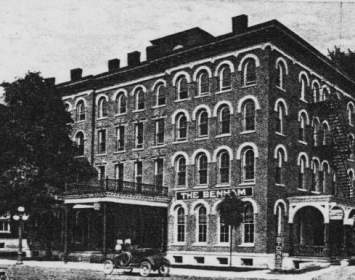

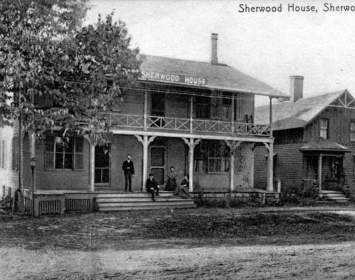

Ingersoll Comes Home Again. Ingersoll returned to the area of his birth only once, in 1889, when he was fifty-six years of age. Accompanied by his daughters Eva and Maud, he traveled to Penn Yan, New York, by rail, lodging at the Benham House, Penn Yan's premier hostelry. On Tuesday, September 24, the Ingersolls toured Dresden, viewing his birthplace, then a private home, and the nearby private residence which had once been his father's church. The next day, Wednesday, September 25, he addressed a crowd of about eight thousand at the Yates County Fair. Appropriately for his rural audience, his remarks were drawn from his famous speech "About Farming in Illinois," coupled with praise for the beauty of the region where he was born.

Ingersoll's Homes and the Importance of the Birthplace. Ingersoll had good taste in real estate. His Washington, D.C., brownstone on Lafayette Square is now incorporated into the Howard T. Markey National Courts Building, home to the United States Court of Federal Claims and United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. His brownstone on Gramercy Park in New York City was razed to make way for the Gramercy Park Hotel, now a glittering boutique hostelry. Aside from a New Mexico ranch given to Ingersoll by a client otherwise unable to settle his bill—where Ingersoll lived briefly before deciding that cattle ranching was not for him—only one of Ingersoll’s residences still stands. Ironically, it is his birthplace in Dresden, New York, where he lived only for the first few months of his life.

Ingersoll's Death and the Aftermath. Ingersoll died on July 21, 1899, while summering at the home of a son-in-law in Dobbs Ferry, New York. News of his death filled newspapers across the nation and across the world. Tributes came from across the ideological spectrum; Ingersoll was publicly mourned by figures ranging from industrialist Andrew Carnegie to socialist and labor activist Eugene V. Debs. Suffrage campaigner Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote to the national freethought newspaper The Boston Investigator, declaring that "No death outside my own family could fill me with such sadness. What a glorious life of self-sacrifice and faithfulness to principle his has been, trying to banish religious superstition from the souls of multitudes of men and women."

In view of his Civil War military service, Ingersoll was buried alongside the ashes of his wife in Arlington National Cemetery.

Ingersoll Remembered Today. The birthplace now houses America’s only freethought museum. The third restoration of the Ingersoll birthplace since 1921, it has been open to the public each summer and fall since 1993 (save for the COVID year of 2020).

An interactive online Chronology documents nearly the whole of Ingersoll's public life. It contains over 2500 events, including most of his public lectures.

An excellent twenty-eight–minute video summarizing Ingersoll’s life and achievements is available here. It is compiled from the 2014 video miniseries American Freethought.

Associated Causes

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

Birth of Robert Green Ingersoll

August 11, 1833

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Ghosts" Lecture in Utica

February 20, 1878

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Individuality" Lecture in Rochester

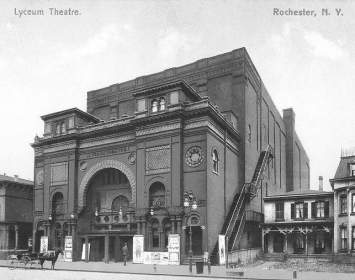

February 21, 1878

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Ghosts" Lecture in Syracuse

February 22, 1878

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Robert Burns" Lecture in Utica

October 30, 1878

Fourth New York Freethinkers Association Convention

September 2–6, 1880

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Orthodoxy" Lecture in Utica

January 19, 1885

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Orthodoxy" Lecture in Auburn

January 21, 1885

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Orthodoxy" Lecture in Oswego

January 23, 1885

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Which Way?" Lecture in Rochester

January 26, 1885

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Orthodoxy" Lecture in Norwich

February 26, 1885

Ingersoll Visits His Birthplace

September 24, 1889

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives Lecture at Yates County Fair

September 25, 1889

Only Return to His Birth County by Robert Green Ingersoll

September 24–25, 1889

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Lincoln" Lecture in Syracuse

April 27, 1894

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Foundations of Faith" Lecture in Rochester

February 23, 1896

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives Unknown Lecture in Rochester

January 5, 1898

Grave of Mary Livingston Ingersoll Located

December 23, 2015