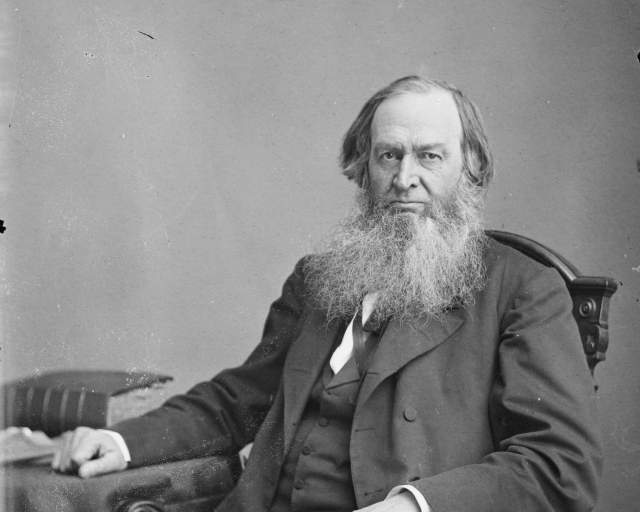

Gerrit Smith (1797–1874) was a free thinker, but not a "freethinker" in the narrower sense of one who rejected Christianity. He remained a Christian, albeit a radical one, throughout his life. But in every other way, Smith exemplified the radical reform impulse and the astonishing cross-fertilization of causes and people that distinguishes the Freethought Trail.

Smith was pre-Civil War America’s foremost philanthropist and reformer. He became a seminal figure in the abolition movement, a major participant in the Underground Railroad, and a significant figure in the woman's suffrage movement, some of whose leading figures were closely associated with him. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) In addition, he took a strong interest in the dress reform movement of the 1850s, which sought more practical and healthful clothing for women. His daughter, Elizabeth Smith Miller, is credited with developing dress reform’s signature garment: the Bloomer costume, consisting of Turkish-style pantaloons under a mid-length skirt.

Smith was also the prototype for a conspicuous American stereotype, the child of great wealth who takes up liberal causes. His father, Peter Smith, made a fortune in the fur trade as a partner to John Jacob Astor (1763–1848) and established the village of Peterboro, New York, in 1795, naming it for himself. In 1804, Peter established the homestead that would become the Gerrit Smith Estate, occupying a new house on the site in 1807.

Gerrit Smith built his own fortune through inheritance and through his own business acumen. In 1819 he purchased a large tract of land in central New York from his father. While his father financed the transaction, Gerrit eventually paid him in full. In addition, he inherited much additional land and a significant fortune upon Peter's death in 1837. His empire's subsequent growth was his own work, including his ownership and development of much of Oswego, then a booming Lake Ontario port city.

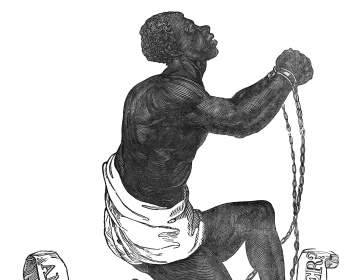

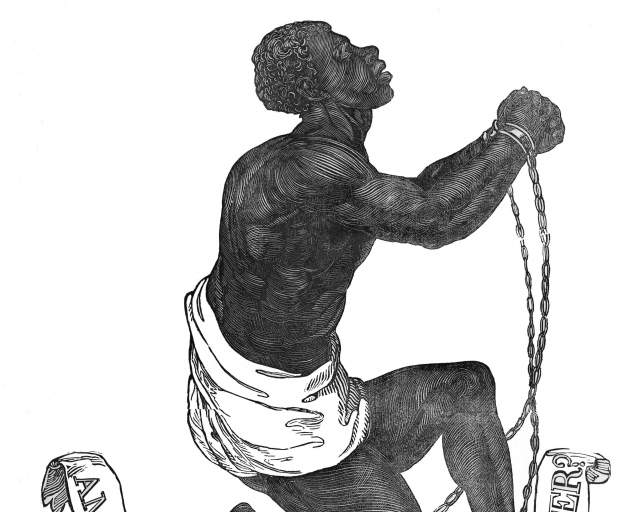

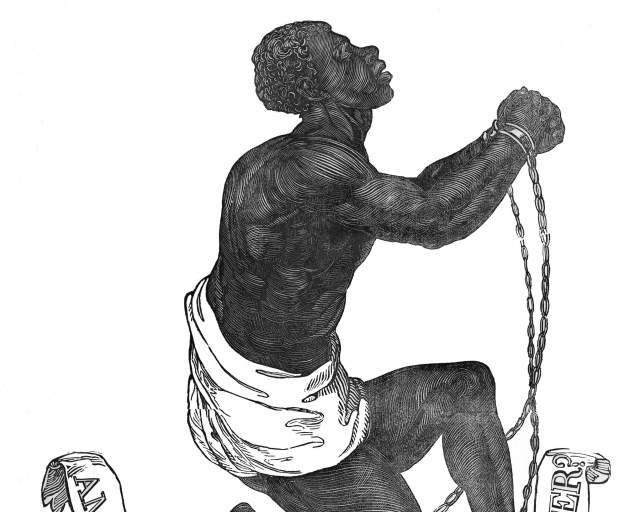

Gerrit built a mansion and other buildings on the homestead site, married Ann Carroll Fitzhugh (1805–1875), and began devoting his energy and wealth to reform causes of the day, including abolition, temperance, and woman's suffrage. A stationmaster on the Underground Railroad, he lodged hundreds of fugitive slaves, frequently purchasing their freedom, facilitating their passage to Canada utilizing his large holdings in Oswego, or assisting them in settling in New York State. His home became a salon that leading reformers, politicians, and businesspeople visited to discuss pressing issues.

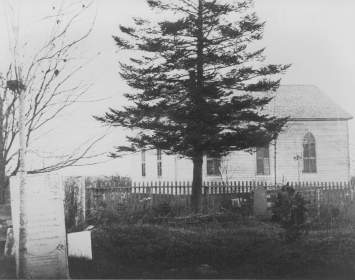

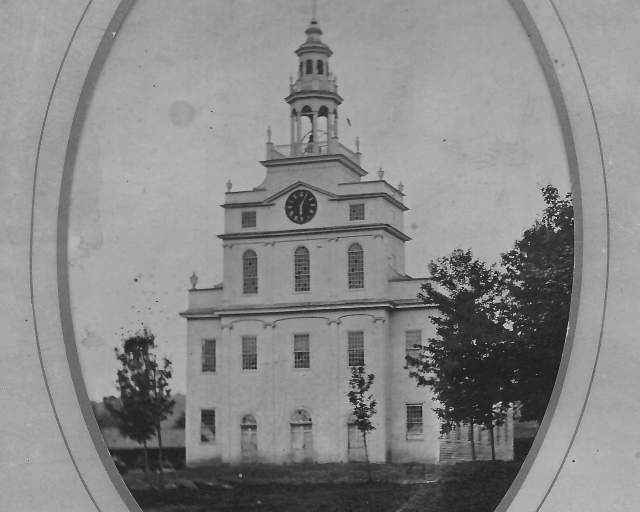

On October 21, 1835, Smith attended the inaugural meeting of the reconstituted New York State Anti-slavery Society at Utica’s Second Presbyterian Church. The meeting was disrupted by a mob. Smith invited all of the delegates to travel to Peterboro that night and complete their meeting there the next day. Three to six hundred of them did so. On October 22, New York’s first public antislavery meeting was completed at Peterboro’s Presbyterian Church; the experience prompted Smith to abandon his former advocacy of colonization—the repatriation of enslaved blacks to Africa—and take up "immediatism," the demand for slavery to be abolished immediately. The Peterboro meeting site is now home to the National Abolition Hall of Fame.

In October 1845, Smith traveled to Boston and addressed a major regional antislavery convention. His lecture was so well regarded that on the spot he was invited to deliver it on five more occasions.

Smith befriended and mentored Frederick Douglass upon the latter's move to Rochester in 1847. Smith influenced Douglass to move beyond the views of his previous sponsor, the Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, embracing a more radical form of immediatist abolitionism.

Smith organized an August 21–22, 1850, convention at Cazenovia to express opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law passed earlier that year. The event featured fifty fugitive slaves and attracted hundreds of abolitionists including Douglass, James Caleb Jackson, Angelina Grimké, and Theodore Dwight Weld. A Daguerrotype of convention speakers became a famous image of the abolition movement. Smith followed up mere days later with another two-day convention at a Peterboro church at which Frederick Douglass gave a major address.

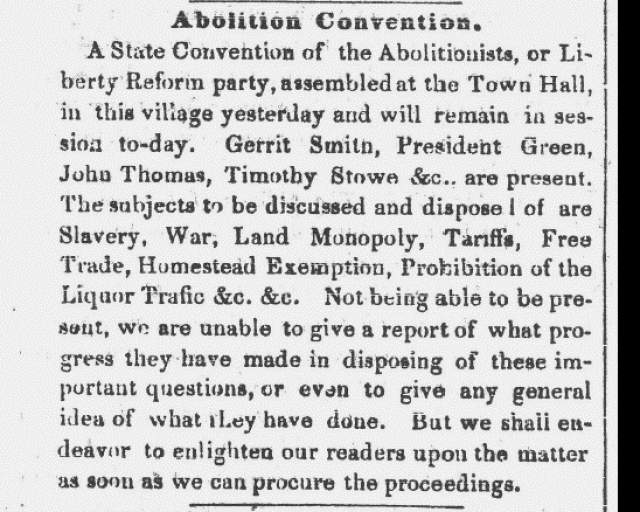

Politics. In 1840, Smith helped organize the Liberty Party, the first openly abolitionist political party. In February 1842, he hosted a New York State Liberty Party convention at his mansion in Peterboro. Several Liberty Party candidates won election to local offices, though the party was markedly less successful at the state and federal level.

Beginning in 1845, the Liberty Party became divided over whether or not to take reformist positions on issues other than slavery. Smith was on the side of those who preferred to maintain the party's purity of focus. Smith, Frederick Douglass, and others founded the Liberty League, originally intended as a special interest group within the Liberty Party. At a meeting in Macedon Lock (modern-day Macedon) in June 1847, the Liberty League reconstituted itself as a political party in its own right.

Overall, Smith would be nominated for president of the United States four times by various parties, and for governor of New York once.

By the 1848 presidential campaign, the Liberty Party had been significantly weakened, both by its internal divisions and by the rise of the Free Soil movement, a loose but powerful coalition that had among its goals to ensure that newly acquired U.S. states and territories were free, not slave. It is estimated that 80 percent of New Yorkers who had voted Liberty in 1844 transferred their loyalty to Free Soil; Smith's Liberal League remained as a home for purists still committed to a single-issue antislavery party. But Smith became dissatisfied with it, and in June 1848, he founded yet another abolition party, the National Liberty Party, out of the Liberal League. Even so, Smith was nominated as the Liberty Party's presidential candidate; his acceptance speech at the party’s convention in Buffalo, New York, included a bold demand for universal suffrage, explicitly encompassing black and white, male and female. This was an audacious position for an antislavery activist of the time. Smith became the 1848 presidential nominee of three small abolitionist parties: the Liberty League, the National Liberty Party, and the National Reform Association (the only party of the three which Smith did not help organize, and not to be confused with the later National Reform Association [founded 1864] that sought to add Christian language to the U. S. Constitution).

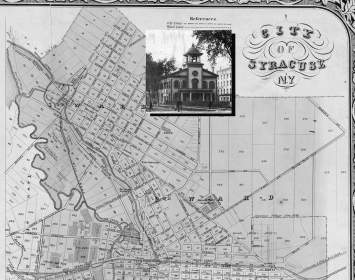

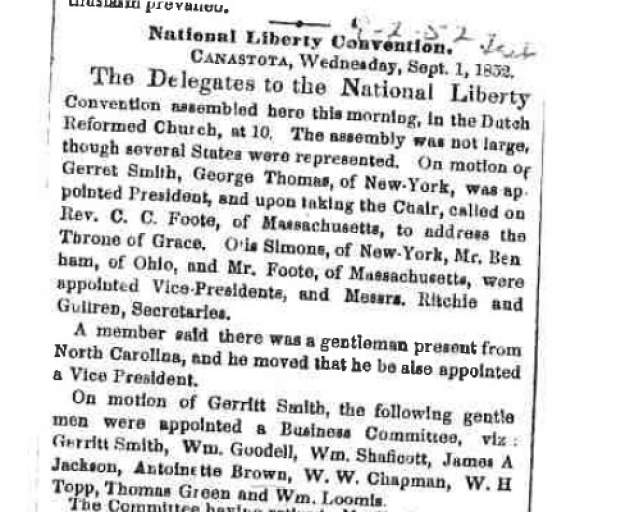

By 1852, the Liberty Party was moribund. The National Liberty Party was tiny and without influence outside New York State. Nonetheless, Smith was again nominated for the presidency at the National Liberty Party's 1852 convention in Oswego. The nomination was of so little importance to him that he did not campaign for president. Instead, a complex series of developments led to his election to the U.S. House of Representatives on an independent ticket. He found serving in Congress disagreeable, it being difficult to interest other legislators in his moralistic calls for reform. He resigned his seat halfway through his term, in August 1854. Despairing of achieving social change through participation in government, he thereafter focused on philanthropy and private organizing—though he did participate in a last-ditch 1855 effort to found still another party, the Radical Abolition Party, at a convention held at Syracuse's City Hall. Little came of this initiative.

Philanthropy. Smith generously supported all the causes he believed in. He built the nation’s first temperance hotel (no alcohol served) at Peterboro and provided lavish support for the abolition movement, the Underground Railroad, and the woman’s movement. It is believed that he funded the first dress reform convention, held in January 1857 in Canastota, just down the road from Peterboro. He was one of the “Secret Six” Northern philanthropists who funded John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, which helped spark the Civil War. (He became so distraught over the raid’s outcome that he suffered a brief nervous breakdown; it remained controversial throughout his life how much he had known regarding Brown’s plans for an armed slave revolt.)

It is estimated that during his life, Mr. and Mrs. Smith donated some eight million dollars (at current values, more than $250 million) to charitable causes. His Peterboro estate became such a center for abolition organizing that African American abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet wrote: “There are yet two places where slaveholders cannot come, Heaven and Peterboro.” Frederick Douglass published this comment on the front page of his Rochester-based abolition paper The North Star on December 8, 1848. (Douglass would later dedicate his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), to Smith.)

Garnet did not exaggerate. Smith spent heavily on flooding the Peterboro area with abolitionist literature and speakers, hoping to demonstrate how profound the impact of intense local campaigning could be. During a single week in November 1843, the seven agents Smith employed in Madison County (where Peterboro is located) conducted an astonishing forty-three antislavery meetings. Another measure of Smith's success was that Madison County supported antislavery candidates, whenever on the ballot, by larger margins than anywhere else in the country. To Smith's disappointment, abolitionists in other areas (none of whom, to be fair, possessed anywhere near his financial resources) failed to follow his lead.

Woman's Rights and Nonpolitical Abolition Protests. On August 2, 1848, two weeks after the woman's rights movement was launched at Seneca Falls, New York, a follow-on woman's rights convention was held in Rochester. Smith was unable to attend but sent a letter expressing his support, which was read out before the convention.

In October 1851, Smith exhorted Syracuse-area abolitionists to defy the new law. On the evening of October 1, reformers and activists broke down the door of a police station to free William "Jerry" Henry, an escaped slave being held pending his forcible return to Missouri. The raid, known as the Jerry Rescue, was successful. "Jerry" escaped to freedom in Canada within a few days; the event galvanized abolitionists nationwide. Afterward, Smith lauded the rescue as the epitome of abolitionist principles in action, urging his colleagues to operate always at the "Jerry Level." He would later grow disillusioned when this high degree of abolitionist fervor was not maintained.

Dress Reform. On January 7–8, 1857, Smith attended the first significant dress reform convention, held at Canastota, just a few miles north of Peterboro. In all likelihood, Smith paid the costs of the event. Attendees included Mary Edwards Walker of Oswego, who would become the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor and would adopt radical reform dress for the rest of her life.

So adamant was Smith in his belief that dress reform alone would improve the condition of women that his daughter Elizabeth Smith Miller felt compelled to continue wearing the Bloomer costume for several years after other suffragists abandoned the fashion.

Death and Funeral. While visiting New York City in 1874, Gerrit Smith suffered a stroke on December 26. He deteriorated rapidly and died on the afternoon of December 28 at age seventy-seven. His body was returned to Peterboro, arriving on December 31. He was interred on the same day. Though he had stated during his life that he did not want a grandiose funeral, his family and the many around Peterboro he had assisted with his charity were having none of it. The Smith mansion overflowed with mourners, among them Smith’s cousin Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Some five hundred people braved temperatures of -20° F, making a half-mile procession to Peterboro Cemetery, where his body reposes today.

Statements of praise for the fallen philanthropist came from every corner of the republic. Though Smith had had many bitter conflicts over strategy with the famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, after Smith’s death Garrison praised him, writing: "His case is hardly to be paralleled among the benefactors of mankind in this or any other country."

Family Links. Smith’s personal connections were as impressive as his activism. He was cousin to the future Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who met her future husband Henry Brewster Stanton at a social event at Smith’s mansion. (The Stantons named their third child, born 1845, after Smith.) Gerrit's daughter Elizabeth (Smith Miller) at one time lived across the town green from her father’s estate and became a suffragist and a philanthropist in her own right. Her role in developing the Bloomer costume (named for its most conspicuous promoter, Seneca Falls activist Amelia Bloomer) has already been mentioned.

Smith's Physical Legacy. The Smith mansion burned down in 1936. The Gerrit Smith Estate was declared a National Historic Landmark in 2001. The former Peterboro Presbyterian Church was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994; in 2004, it became the home of the National Abolition Hall of Fame.

Thanks to Norman K. Dann for extraordinary research assistance.

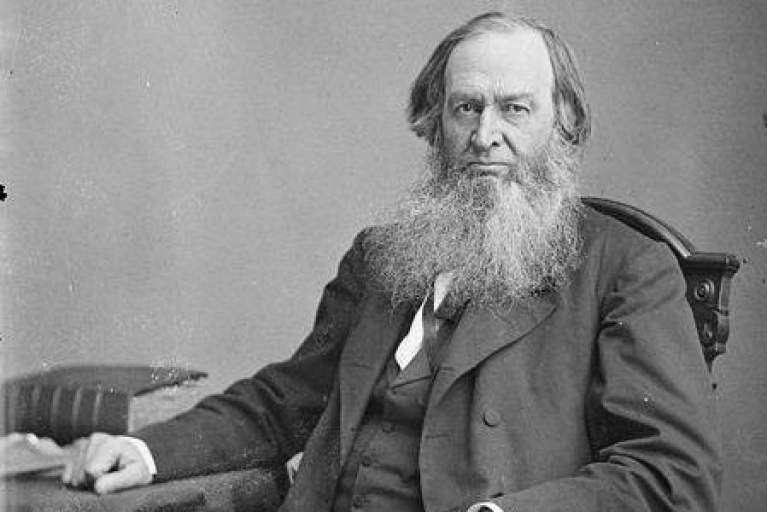

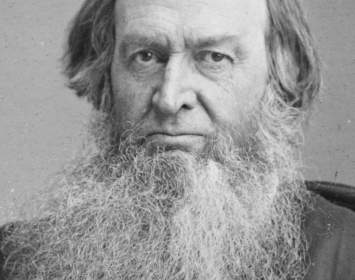

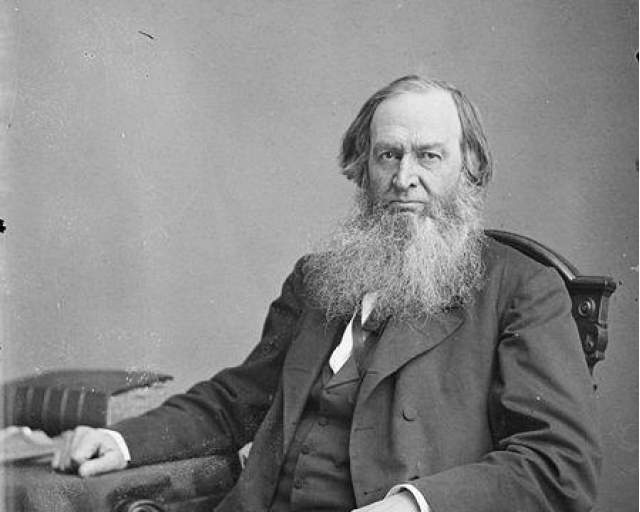

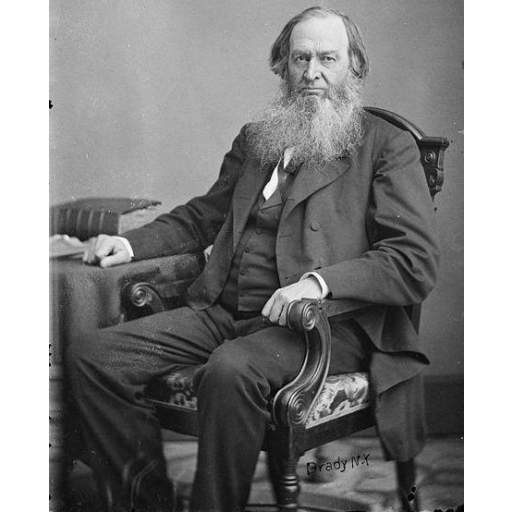

Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith, photographed by Mathew Brady.

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

First New York State Antislavery Meeting

October 21–22, 1835

Meeting to Plan Establishment of the Liberty Party

January 1840

New York State Abolition Convention

January 19–20, 1842

First Liberty League Convention

June 8, 1847

Second Liberty League Convention

January 13–14, 1848

Follow-On Woman's Rights Convention

August 2, 1848

New York State Convention of the Liberty League and National Reform Party

September 28, 1848

Fugitive Slave Law Convention at Cazenovia

August 21–22, 1850

Fugitive Slave Law Convention at Peterboro

Late August, 1850

The Jerry Rescue

October 1, 1851

Liberty Party Convention at Canastota

September 1852

Third National Woman’s Rights Convention

September 8–10, 1852

National Liberty Convention

September 30, 1852

National Liberty Party Convention

October 2, 1852

Radical Abolition Party Formation

June 26–28, 1855

First Annual Meeting of the NDRA

June 18 - 19, 1856

First National Dress Reform Association Convention

January 7–8, 1857

Funeral of Gerrit Smith

December 31, 1874