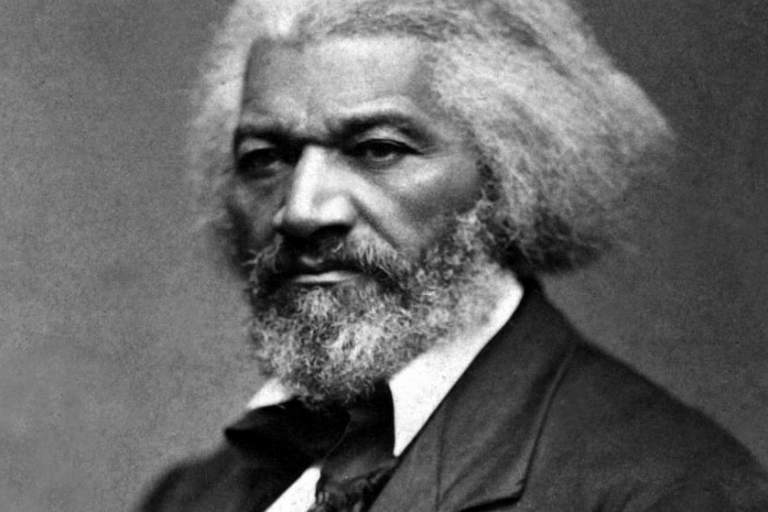

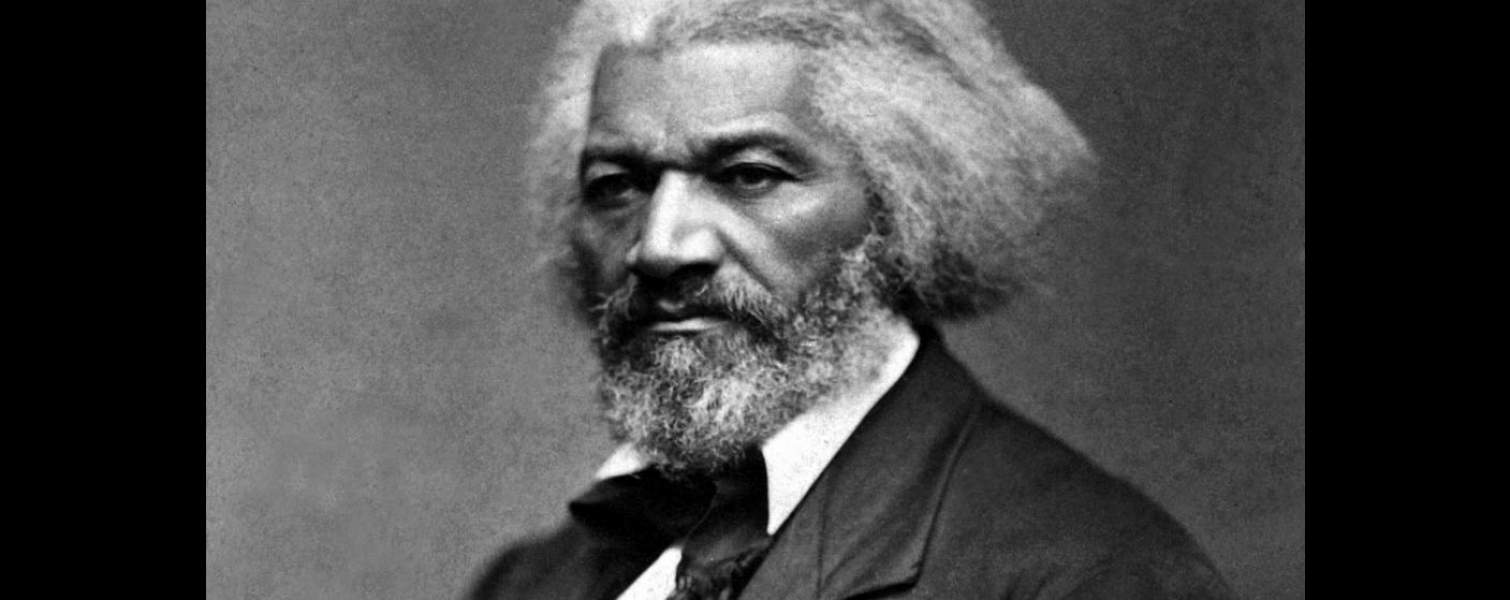

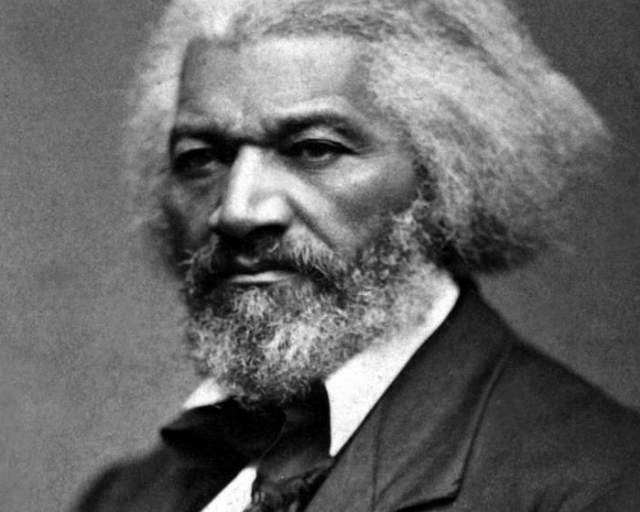

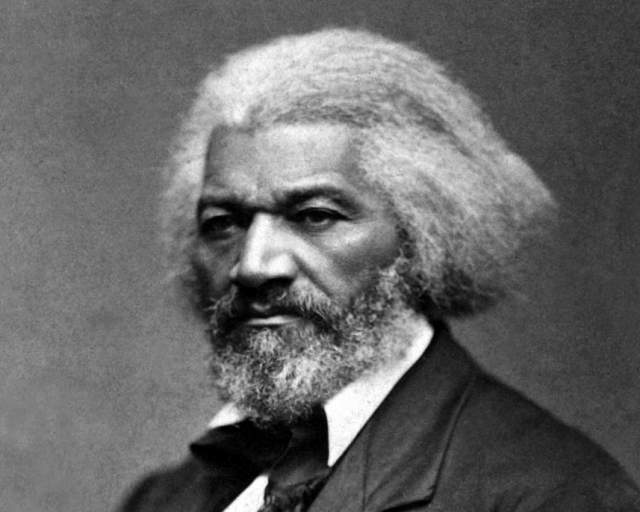

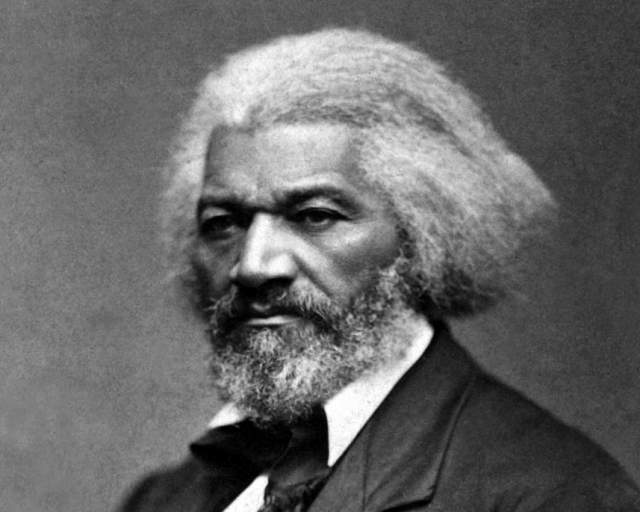

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was an escaped slave who became one of the most charismatic and forceful leaders of the American abolition movement. He spent the most productive twenty-five years of his life in Rochester, where he excelled as an orator and as the editor of the newspaper The North Star and other renowned anti-slavery publications.

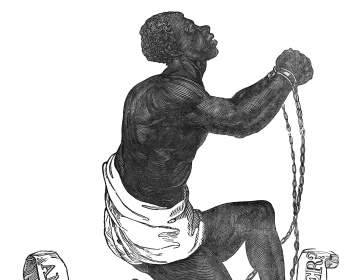

He was born Frederick Bailey at Holme Hill Farm in Easton, Maryland. His mother was a slave; his father was presumably the farm’s white owner. Frederick learned to read in childhood. As a young man he briefly embraced Christianity but soon abandoned it, observing that the religion did so little to soften the behavior of slave owners. At the age of twenty he made his daring escape. (In later life, he would remark that "Praying for freedom never did me any good til I started praying with my feet.") He adopted the colorful surname "Douglass" from a character in "The Lady of the Lake," a poem by Sir Walter Scott. He was soon a popular speaker at abolition meetings.

In 1847, Douglass moved to Rochester. Amid a community rich with reform-minded people, he hoped to establish himself as a national figure in the anti-slavery movement. He succeeded. His newspaper The North Star (1847–1851) was widely influential. The building where he published it—and sometimes hid fugitive slaves—still stands.

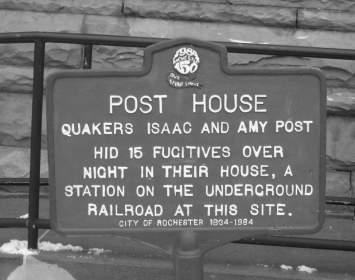

Douglass built warm friendships in Rochester’s abolitionist community, among them the radical Quakers Isaac and Amy Post (his hosts when he first came to the city) and the famed abolitionist and feminist activist Susan B. Anthony. Radical millionaire philanthropist Gerrit Smith of Peterboro, New York, became a mentor to Douglass and an early financial supporter of The North Star.

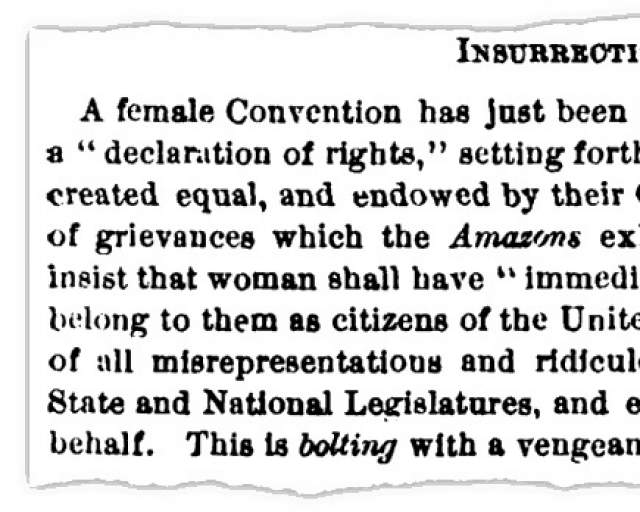

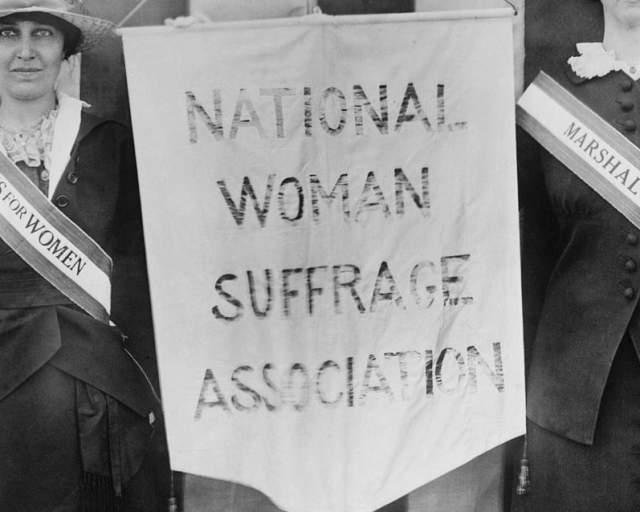

In July 1848, Douglass and Amy Post traveled to Seneca Falls, New York, where they attended the Woman’s Rights Convention that sparked the nineteenth-century woman suffrage movement. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) He was the only male to speak at the convention, drawing parallels between black men and American women as equally disenfranchised. The site of this historic convention has been restored and also houses an impressive museum, all operated by the National Park Service. In the museum, an assemblage of life-sized statues of conference participants includes an excellent likeness of Douglass.

Douglass freely acknowledged his debt to Gerrit Smith, who generously supported abolition activism and the Underground Railroad from his estate in Peterboro, New York. In the December 8, 1848, edition of The North Star, Douglass reserved the front page for these words by African American abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet: "There are yet two places where slaveholders cannot come, Heaven and Peterboro." When the North Star was about to fail for lack of subscribers, Smith merged his own Liberty Party paper into it, giving Douglass control of the resulting publication. Frederick Douglass’s Paper continued publishing until 1859. Douglass would later dedicate his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), to Smith.

On August 21–22, 1850, Douglass attended a Cazenovia convention opposed to that year's Fugitive Slave Law that featured fifty fugitive slaves and attracted hundreds of abolitionists including Gerrit Smith, the convention's organizer; James Caleb Jackson; Angelina Grimké; and Theodore Dwight Weld. A Daguerrotype of convention speakers (see first and second photos directly below text on this page) became a famous image of the abolition movement.

Douglass was active with the Underground Railroad. At one point in 1851, he sheltered a party of eleven fugitives led by Sojourner Truth.

Angered by passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Douglass delivered his famous "Fifth of July" address on July 5, 1852, at Rochester’s Corinthian Hall. (Emancipation of slaves in New York—which occurred on July 4, 1827—was traditionally celebrated on July 5 so as not to conflict with Independence Day observances.) In thunderous language he condemned America’s July Fourth holiday as a hollow fraud because there was neither dignity nor freedom for Americans whose skin was black. He reserved some of his harshest language for pro-slavery Christian clergymen: "I would say welcome infidelity! Welcome atheism! Welcome anything! In preference to the gospel as preached by those divines! They convert the very name of religion into a barbarous cruelty." Many historians consider this the most important anti-slavery speech of the years leading up to the Civil War. Sadly, its site is now a city parking structure.

Douglass was a good friend of the agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll. Douglass once remarked that Ingersoll and Lincoln were the only white men in whose company "he could be without feeling he was regarded as inferior to them."

Douglass owned two homes in Rochester—one close to downtown, its site unmarked, the other outside the city limits (though well inside them today). The latter site contains a highly informative historical marker. Neither home stands today. He owned a third home which has survived, though for many years it was not known as Douglass's because he had registered it under his daughter's married name. During and after the Civil War Douglass became a figure of international stature and spent much of his time in Washington, D.C. In 1872, he and his family moved permanently to the nation’s capital after a suspicious fire destroyed their home in rural Rochester.

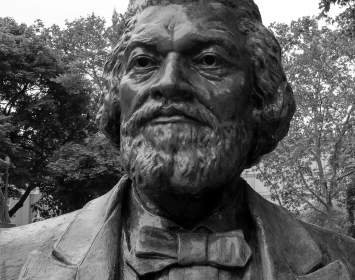

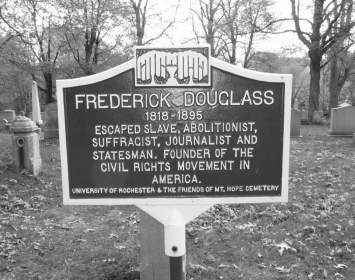

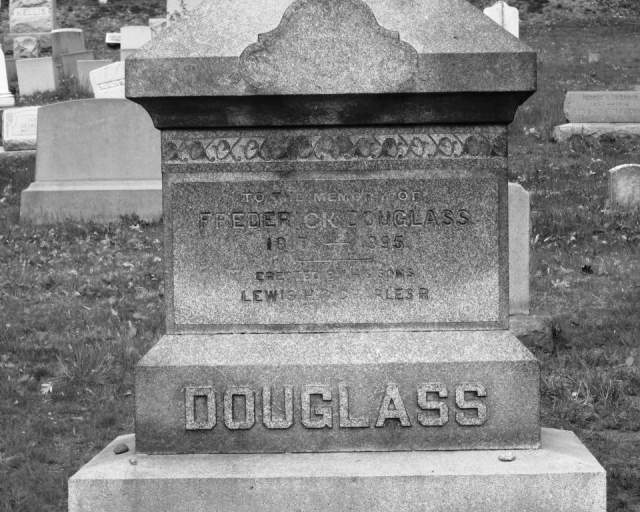

Douglass died in Washington on February 20, 1895. Following funeral and memorial services there, his remains were brought to Rochester, where on February 26 a large memorial service was held at the city’s Central Church. A large delegation accompanied his body to Mount Hope Cemetery, where his grave site is now a principal attraction. A statue of Douglass by sculptor Sidney W. Edwards was installed before the city’s train station in 1899; in 1941, it was moved to a location overlooking the Highland Park Bowl in 2019 it was moved again to a more visible location.

Douglass’s credentials, not only as an opponent of slavery but as a freethinker, are robust. To add but one further example, consider his 1870 open letter to the Philadelphia Press: "During forty years of moral effort to overthrow slavery in this country, this system with all its hell-black horrors and crimes, found no more secure shelter anywhere than amid the popular religious cant of the day. One honest Abolitionist was a greater terror to slaveholders than whole acres of camp-meeting preachers shouting glory to God."If slavery were to be destroyed, Douglass believed, human beings would have to do it for themselves. And so they did.

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895)

Frederick Douglass.

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

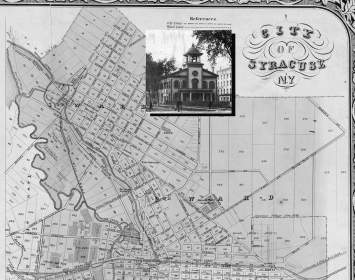

Frederick Douglass Outdoor Lecture Series at Syracuse

July 30–August 2, 1843

First Liberty League Convention

June 8, 1847

Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls

July 19–20, 1848

Follow-On Woman's Rights Convention

August 2, 1848

Fugitive Slave Law Convention at Cazenovia

August 21–22, 1850

Fugitive Slave Law Convention at Peterboro

Late August, 1850

Frederick Douglass Gives "Fifth of July" Speech

July 5, 1852

Radical Abolition Party Formation

June 26–28, 1855

Rochester Antislavery Convention

February 13–14, 1857

1878 Woman's Rights Convention

July 19, 1878

Funeral and Burial of Frederick Douglass

February 26, 1895