Popular understanding often associates abolitionism (the campaign to end slavery) with the churches. In fact, the opposite is true.

The earliest critics of slavery were anything but religious; most were eighteenth-century rationalists in the Enlightenment tradition who had come to view slavery as contrary to the recently articulated "rights of man." Somewhat later, pioneer Quaker abolitionists branded slavery "un-Christian." Slavery was outlawed in Britain in 1772, and in the United States, states north of Maryland between 1777 and 1804. These reforms were generally the work of political, not religious, activists.

Prior to about 1840, those ministers and other religious activists who embraced abolitionism tended to be radicals within liberal denominations, notably the Unitarians and Quakers.

By the mid–nineteenth-century, preachers and their congregants were about evenly divided between attackers and defenders of slavery, even in northern states. (Defenders could note that Jesus condoned slavery in the New Testament. Furthermore, in the words of the late secular religion scholar Hector Avalos, "That slavery was accepted and endorsed throughout the Bible needs little demonstration.")

Early History. The American abolition movement arose in response to the recognition that slavery south of the Mason-Dixon line would not dissolve under the pressure of moral suasion. Early activists included William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879), a journalist and activist who personally inspired most of the other principal abolitionist leaders. Among these was the nondenominational minister Beriah Green (1795–1874); at this time, declining to align with any established denomination was a radical stance. Green preached America’s first abolitionist sermons in Ohio in 1832; from 1833 to 1844, he led the Oneida Institute, a labor college that pioneered integration of black and white students. (Oneida was located in the ironically named Whitesboro, near Syracuse.)

Speaking of irony, Beriah Green was a friend of the Rev. John Ingersoll, who gave his youngest son the middle name Green in Beriah’s honor. This child was Robert Green Ingersoll (1833–1899), who would become the best-known and most influential agnostic orator in the nation’s history. (Ingersoll’s birthplace is an attraction on the Freethought Trail.) Other early activists included the radical Unitarian cleric Theodore Parker (1810–1860) and the freethinking author Lydia Maria Child (1802–1880).

Abolition and Church Schisms. Beginning in the 1830s, many Protestant denominations schismed (or split) over the slavery question. Best known among these may be the Southern Baptist Convention, which broke from its parent denomination in order to mount a vigorous, principally religious defense of slavery. In the north, churches tended to split along different lines: more conservative churches advocated continuing tolerance of slavery in the existing slave states, and neutrality whether states newly entering the Union would be slave or free. Some gave lip service to the idea of abolition, but argued for pursuing reforms very slowly so as to minimize social disruption. More liberal northern churches took a "Free Soil" position that all states newly joining the Union should prohibit slavery.

More radical activists advocated for slavery's immediate abolition. Such activists powerfully influenced the Wesleyan Methodist Church, which withdrew from its parent Methodist Episcopal Church in 1841 over slavery. Wesleyan congregations tended to be strongly socially liberal. Some of their ministers supported agendas so radical that they were only marginally distinguishable from freethought. Many Wesleyan churches served as stations on the Underground Railroad and made their facilities available for abolition meetings; after the Civil War they would frequently host woman suffrage events. (For example, the 1848 woman's rights convention in Seneca Falls that launched the nineteenth-century suffrage movement took place in a Wesleyan chapel.)

Modern-day defenders of Christianity have exploited the fact that some nineteenth-century Christians worked for abolition to promote a false narrative that most abolition work took place in the churches. yet it did not. "Having generally endorsed slavery for some 1900 of the last 2000 years," writes Hector Avalos, "Christianity can claim little credit for abolishing something that it could have abolished 1900 years earlier." It is the freethought contribution to abolition that deserves to be more widely recognized.

Abolition in West-central New York. With its social ferment, its friendliness toward radical reformers, and its proximity to the Canadian border, west-central New York State was home to many notable abolitionists. From his estate at Peterboro, millionaire activist-philanthropist Gerrit Smith not only inspired but personally funded abolitionist and Underground Railroad activities. The first complete public abolition meeting took place at Smith’s behest in Peterboro; the site now houses the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum.

Other notable area activists included C. D. B. Mills of Syracuse, Susan B. Anthony of Rochester, and Matilda Joslyn Gage of Fayetteville.

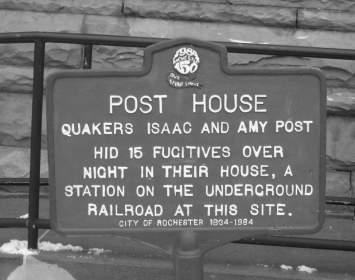

Rochester was a special hotbed of abolitionist sentiment. The Quaker activists Isaac and Amy Post (1798–1872 and 1802–1889, respectively), former slave Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), and Susan B. Anthony frequently collaborated on abolitionist matters. They also exemplified the cross-fertilization between reform traditions so characteristic of the Freethought Trail. The abolitionists Anthony, Gage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Amy Post were also committed suffragists; the latter three were also notably active as freethinkers. For example, Amy Post attended the 1878 conference of the New York State Freethinkers Association held at Watkins, now Watkins Glen.

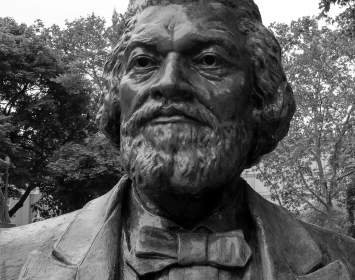

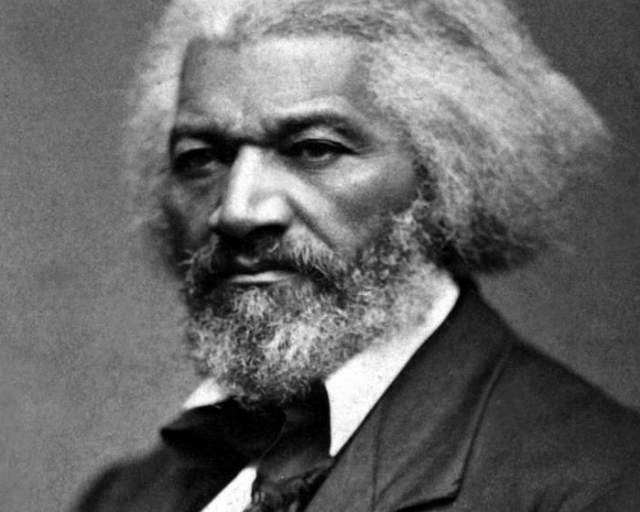

Susan B. Anthony is of course better known for her woman’s suffrage activism than for her significant abolitionist work. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) Douglass was an outspoken freethinker, a friend of Robert Ingersoll, and an attendee at the 1848 Seneca Falls convention that launched the woman’s rights movements and the reform career of freethinker Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902). All the activists named in this paragraph participated in the Underground Railroad and at various times harbored escaped slaves in their homes.

Abolitionism and Politics. By most metrics, west-central New York State was the nation's number-two center of abolition activism, trailing New England. But when it came to abolitionist politics, New York clearly took the lead. The first antislavery political party, the Liberty Party, was founded in Albany in 1840. The party was initially planned at a meeting at Gerrit Smith's Peterboro estate in January of that year. Among its founders was, of course, Gerrit Smith. Some candidates ran successfully for local officers on the party's line. But it was best known for its unsuccessful presidential tickets in 1840, 1844, and 1848. While the party had branches in other states, the great majority of its interest and support came from New York.

By 1848 internal divisions had weakened the Liberty Party; only one of its splinters, the National Liberty Party, fielded a presidential slate in 1852. (Unsurprisingly, Smith was its presidential candidate.) During its twelve-year run, the Liberty Party and its offshoots never elected a candidate. But they galvanized liberal opinion in the North in favor of abolition. They put antislavery politics in the spotlight and paved the way for the rise of the Free Soil movement (1848) and the Republican Party (1854), whose now-mainstream antislavery stance resembled that of the Liberty Party, which had been viewed as marginal for advocating many of the same things just a decade previously. The political arm of the abolition movement managed its last gasp, the formation in 1855 of a Radical Abolition Party at Market Hall in Syracuse, that yielded few results. (For more on the abolition-focused minor parties, see Gerrit Smith's biography page.)

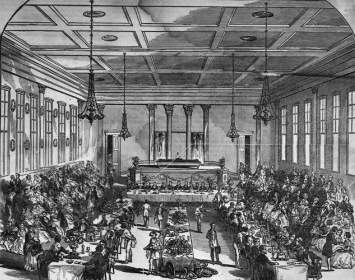

Perhaps no quotation better captures the power of the freethinkers’ case against slavery than this fiery passage delivered by Frederick Douglass at Rochester’s long-lost Corinthian Hall on July 5, 1852: "I would say welcome infidelity! welcome atheism! welcome anything! in preference to the gospel as preached by those divines [i.e. clergy who defend slavery]! They convert the very name of religion into a barbarous cruelty."

Thanks to Norman K. Dann for extraordinary research assistance.

Quotations from Hector Avalos, The Reality of Religious Violence (Sheffield, U. K.: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2019), pp. 416-17.

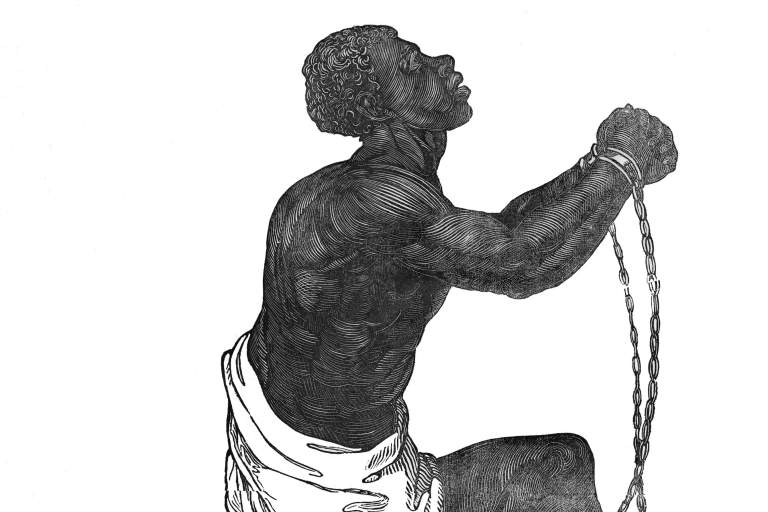

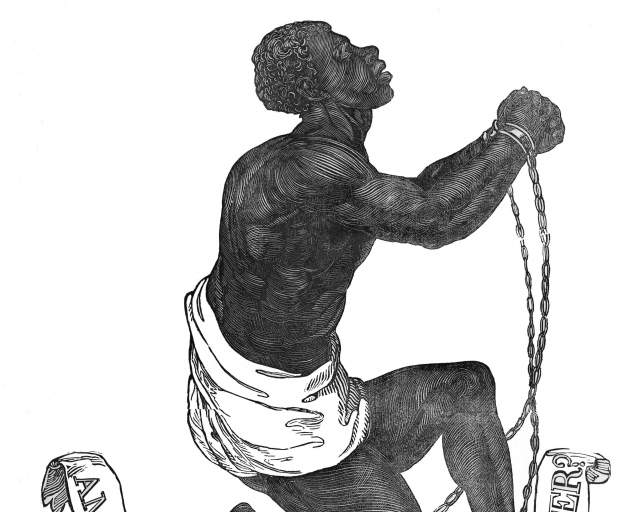

Abolition logo hi-res

This image was an often-used emblem of the abolition movement.

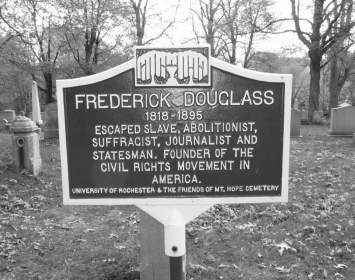

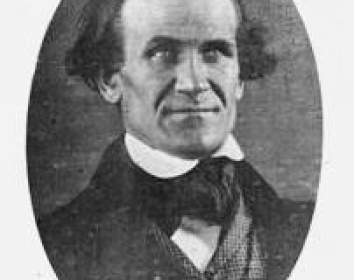

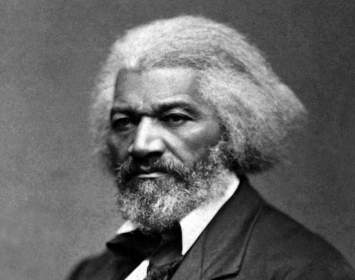

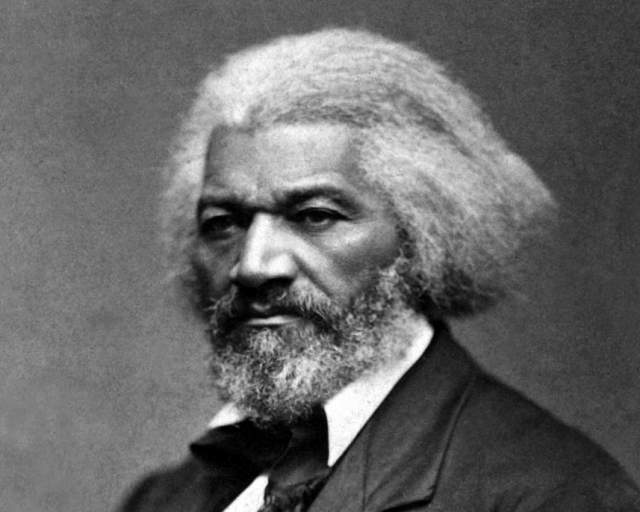

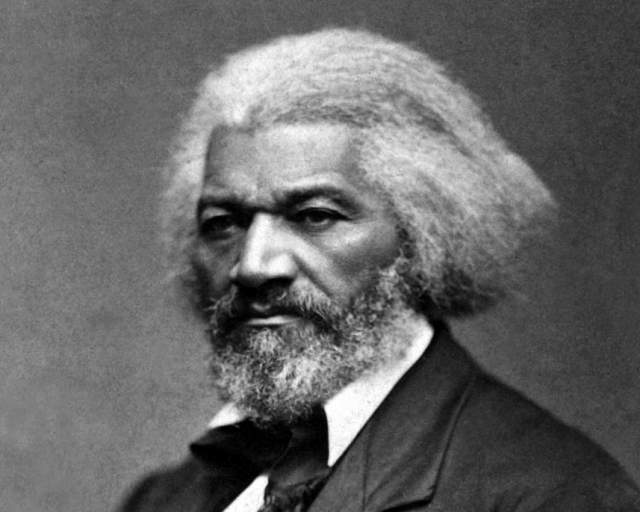

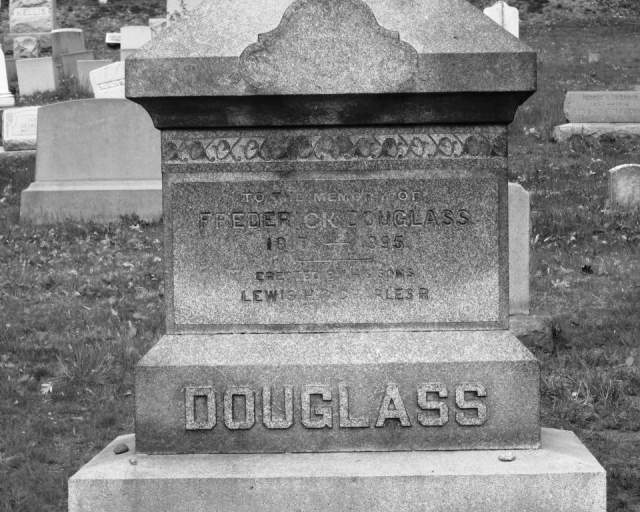

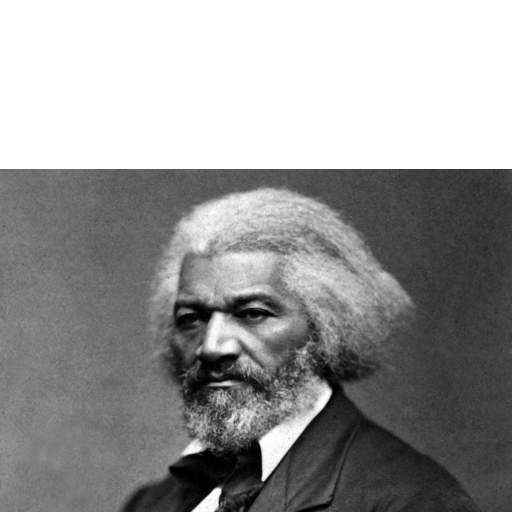

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), an escaped slave, became one of the most charismatic and forceful leaders of the American abolition movement. He spent the most productive twenty-five years of his life in Rochester, where he excelled as an orator and as the editor of the newspaper The North Star and other renowned anti-slavery publications. Though he moved to Washington, D. C., in 1872, he continued to think of Rochester as his true home and was buried there following his death.

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) began her career in activism as an abolitionist. She worked closely with Frederick Douglass and others, helping to make Rochester one of the nation's centers of abolitionist ferment, before emerging as one of the three major leaders of the woman suffrage movement alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage -- both of whom had also begun their activist careers in abolition.

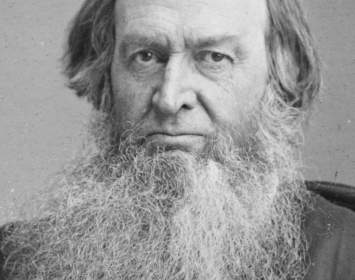

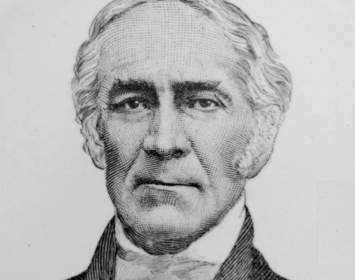

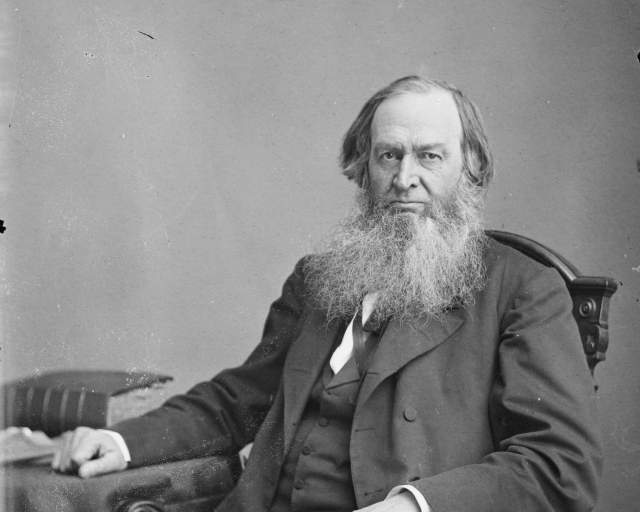

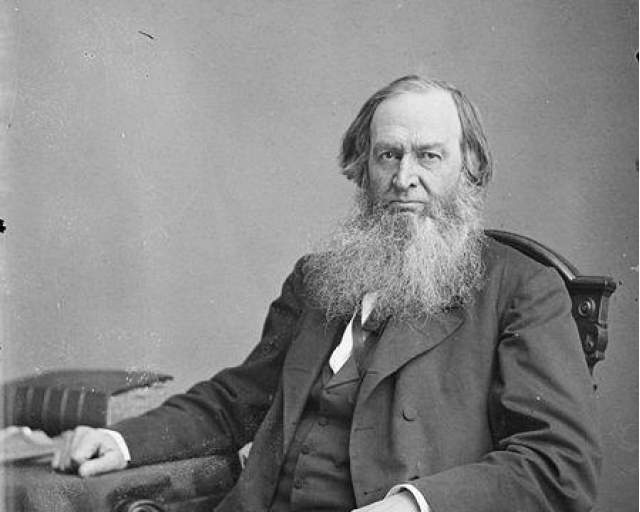

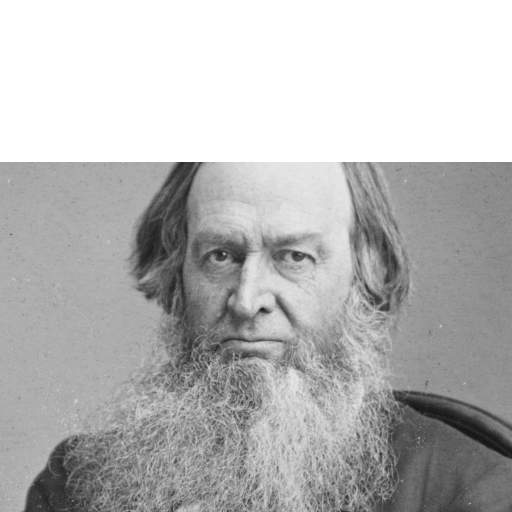

Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (1797–1874) was pre-Civil War America’s foremost philanthropist and reformer. The Peterboro resident became a seminal figure in the abolition movement, and major participant in the Underground Railroad; he owned most of the Oswego waterfront, through which hundreds escaped to freedom in Canada. He conducted the first completed antislavery meeting in New York. He was also one of the "Secret Six" wealthy Northerners who funded John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry, West Virginia, though it is unclear to what degree Smith was privy to Brown's full intentions.

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

First New York State Antislavery Meeting

October 21–22, 1835

Oswego County Anti-Slavery Society Annual Meeting

January 17, 1839

Meeting to Plan Establishment of the Liberty Party

January 1840

New York State Abolition Convention

January 19–20, 1842

Frederick Douglass Outdoor Lecture Series at Syracuse

July 30–August 2, 1843

First Liberty League Convention

June 8, 1847

Second Liberty League Convention

January 13–14, 1848

New York State Convention of the Liberty League and National Reform Party

September 28, 1848

Fugitive Slave Law Convention at Cazenovia

August 21–22, 1850

Fugitive Slave Law Convention at Peterboro

Late August, 1850

The Jerry Rescue

October 1, 1851

Frederick Douglass Gives "Fifth of July" Speech

July 5, 1852

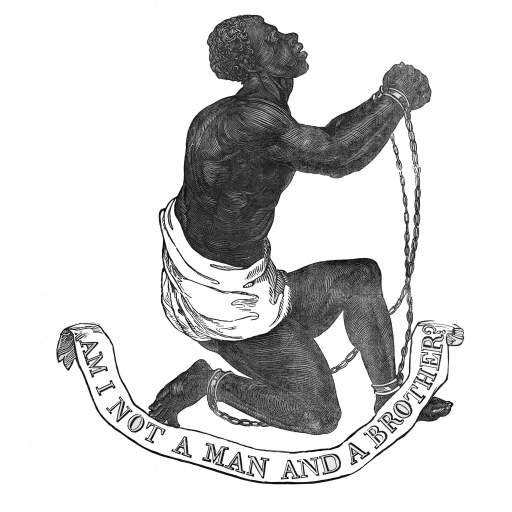

Liberty Party Convention at Canastota

September 1852

National Liberty Convention

September 30, 1852

National Liberty Party Convention

October 2, 1852

Radical Abolition Party Formation

June 26–28, 1855

Rochester Antislavery Convention

February 13–14, 1857

Meeting of Mourning and Eulogy for John Brown

December 2, 1859

Death of Hezekiah Joslyn

October 30, 1865

Funeral of Gerrit Smith

December 31, 1874

Funeral and Burial of Frederick Douglass

February 26, 1895