Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) dedicated her life to the causes of abolition and woman suffrage. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman or woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women or women's.) Anthony was one of Rochester’s leading antislavery activists; she collaborated with Harriet Tubman on the Underground Railroad. She was a close friend and frequent collaborator of escaped slave-turned-antislavery icon Frederick Douglass, another Rochester resident. From 1851 until her death in 1906, she was at the forefront of the woman’s rights movement. With Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage, Anthony co-led the National Woman Suffrage Association, the radical wing of the movement, through some of its most productive years. Later, the three women (known as "the Triumvirate") cowrote the first three volumes of The History of Woman Suffrage.

Trial for Voting. On November 1, 1872, Anthony and two other women attempted to register to vote in the U.S. presidential election. When registrars hesitated, Anthony overwhelmed them with legal arguments, and the men relented. On Election Day, November 5, Anthony voted for Ulysses S. Grant, one of fifteen women from her Rochester ward to cast a ballot. Attempting to vote was actually a common tactic among suffrage activists; Anthony's action commanded outsized attention because she and her colleagues actually voted, and because Anthony was famously arrested for so doing.

Anthony was arrested on November 18, 1872, and went to trial on June 18, 1873. She was convicted and fined $100, a sum she never paid. She discouraged talk of a pardon during her life; she viewed the conviction as a badge of honor. She was pardoned, however, on August 18, 2020, by President Donald J. Trump.

Later Developments. On July 4, 1876, Anthony read a famous protest document, the Woman’s Declaration of Rights, at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition (the first World’s Fair). Though read out by Anthony, the document had been composed by Stanton and Gage.

Anthony was more conciliatory—some would say pragmatic—in matters of religion than Stanton or Gage. Unlike them, Anthony never blamed the Christian church for institutionalizing the oppression of women; late in her career, she even welcomed the extremely conservative Woman’s Christian Temperance Union into the suffrage movement, causing an enduring split among suffrage activists.

By the early 1880s, Anthony and sometimes Stanton were taking steps to distance themselves from Gage, who was outspokenly critical of religion. (Stanton had not yet gone public with her freethinking views.) When the second volume of The History of Woman Suffrage was published in 1882, it was evident that Anthony and Stanton had rewritten portions of a chapter written by Gage that discussed attempts by women to cast unlawful votes as a means of protest. The published version focused almost solely on Anthony's voting and its aftermath, minimizing similar efforts by Gage and hundreds of other activists. Gage was outraged, but could not prove that her writing had been modified because she had mislaid her original manuscript. (In part because both Anthony and Stanton had their papers burned after their deaths, the published volumes of the History served as an unchallenged information source about the early suffrage movement, leading to a popular misunderstanding that Anthony was the only suffragist who had voted illegally.)

By 1890, the movement had for two decades been divided into radical and moderate wings. Anthony, Stanton, and to a declining degree Gage had led the more-radical National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which sought a broad slate of reforms, including divorce reform and property rights for women as well as the vote. Lucy Stone and others led the more-moderate American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which sought the vote exclusively. Anthony secretly reached out to Stone to heal the rift between NWSA and AWSA. In 1890, the organizations merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The seemingly sudden reunification had in fact been carefully negotiated by Anthony, mostly behind the backs of both Stanton and Gage.

Anthony sought a suffragism that was less culturally radical—and especially, less critical of religion. Stanton and Gage found themselves sidelined from leadership. Yet Stanton's reputation was so great that Anthony persuaded her to accept a figurehead presidency of NAWSA starting in 1890. This precipitated a break with Gage, who had counseled Stanton to stand firm in resisting Anthony's veer toward moderatism.

Also in 1890, Anthony bought out Gage's one-third share in The History of Woman Suffrage. In desperate need of funds, Gage accepted a modest offer from Anthony and later complained of feeling cheated. Gage never again worked for suffrage, turning her talents to freethought activism.

If Anthony had treated her freethinking colleagues cruelly, freethinkers outside the suffrage movement appeared unaware of it. In a February 25, 1896 interview with the Rochester, New York Herald, famed freethought orator Robert Green Ingersoll lavished upon Anthony this outspoken praise: "Miss Anthony is one of the most remarkable women in the world. She has the enthusiasm of youth and spring, the courage and sincerity of a martyr. She is as reliable as the attraction of gravitation. She is absolutely true to her convictions, intellectually honest, logical, candid and infinitely persistent. No human being has done more for woman than Miss Anthony."

Anthony died on March 13, 1906. She had outlived Gage, who died in 1898, and Stanton, who died in 1902. But she never saw her goal of winning woman’s suffrage realized. Nationwide woman suffrage was only achieved on August 26, 1920, with adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In tribute to her leadership, it was sometimes referred to as the "Susan B. Anthony Amendment."

Suffrage: Only for White Women? It is worth noting that woman suffrage did not become universal in 1920. Woman's enfranchisement came just as Jim Crow was taking form in the South. At the same time more subtle methods of suppressing the black vote spread across much of the North. These manifestations of racism meant that many African American women were unable to exercise their franchise until the mid-twentieth century or later, giving rise to a perception that suffrage had benefited primarily white women. But the fact remains that once race-based barriers to voting were removed, it was because of the Nineteenth Amendment—and the suffrage movement that had won it—that women of color faced no further obstacles to voting because of their sex.

History's Treatment of Anthony, Stanton, and Gage. Among the members of the suffrage movement’s leadership "Triumvirate," Anthony—though privately a freethinker—was the most accommodating toward religion. History’s treatment of Anthony, Stanton, and Gage is quite revealing. Early twentieth-century suffragists tended to look back on Anthony as the sole founding leader of the suffrage movement. Stanton, who revealed her infidel views late in life after having already established her reputation as a suffragist, was almost forgotten until her rediscovery by second-wave feminists of the 1960s. Gage, who had been critical of religion throughout her suffrage career, was largely forgotten by history until the 1990s, when her memory was rehabilitated largely through the efforts of feminist scholar Sally Roesch Wagner.

Susan B. Anthony was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester’s premier memorial park. Anthony reposes beneath a rather modest white marker on a family plot. The grave site attracts thousands of visitors annually. Anthony's Rochester home houses a prominent museum interpreting her life and times. She was further honored on the Susan B. Anthony dollar coin, introduced in 1979.

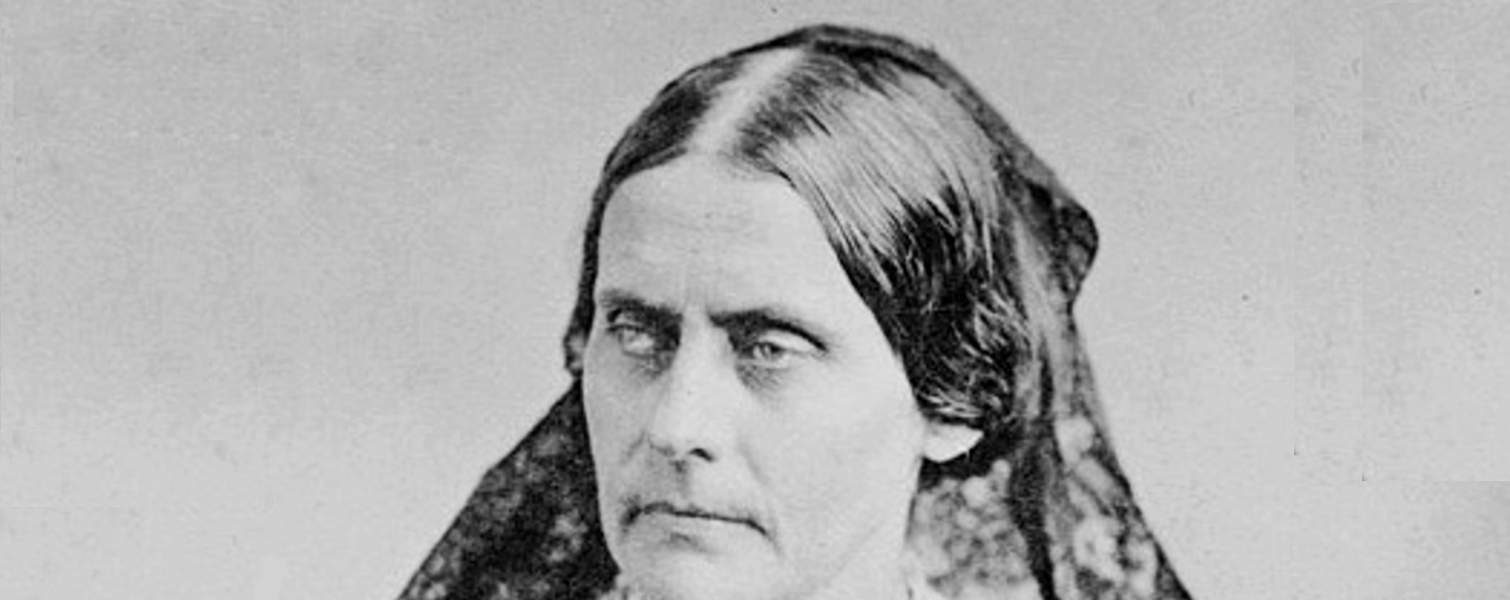

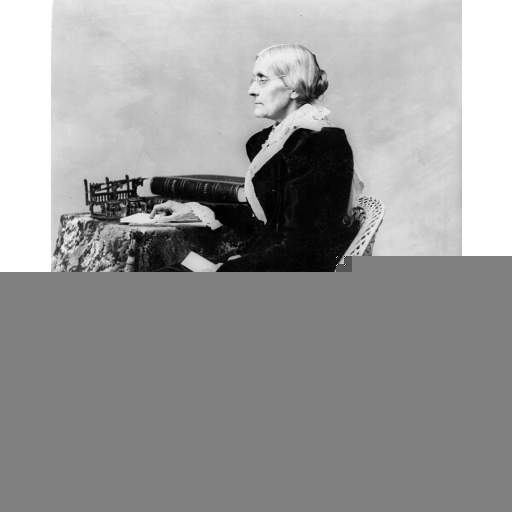

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony in later life.

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

Follow-On Woman's Rights Convention

August 2, 1848

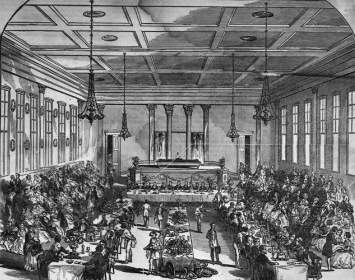

Third National Woman’s Rights Convention

September 8–10, 1852

Woman's Rights Convention in Penn Yan

January 10, 1855

Rochester Antislavery Convention

February 13–14, 1857

Meeting of Mourning and Eulogy for John Brown

December 2, 1859

Susan B. Anthony Lectures at Library Hall

March 26, 1869

The Arrest of Susan B. Anthony

November 18, 1872

The Trial of Susan B. Anthony

June 18–20, 1873

Twenty-Second NY State Suffrage Convention

December 16–18, 1890

Twenty-Third NY State Suffrage Convention

November 10–11, 1891

Local Suffrage Meeting to Amend NYS Constitution

March 27–29, 1894

Susan B. Anthony Lectures in Utica

April 19, 1894

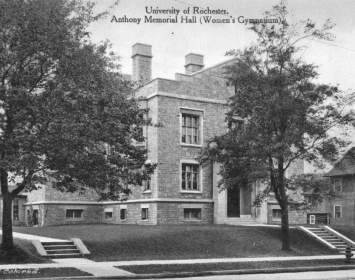

Susan B. Anthony Dines/Speaks at Sage College

November 14, 1894

Twenty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 12–16, 1894

Twenty-Eighth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 17–19, 1896

Twenty-Ninth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 3–6, 1897

Thirty-Third NY State Suffrage Convention

October 29–November 1, 1901

Thirty-Fifth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 20–23, 1903

Thirty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 17–20, 1904

Thirty-Seventh NY State Suffrage Convention

October 24–27, 1905

Death of Susan B. Anthony

March 13, 1906