From after the Civil War until the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920, New York State was a conspicuous leader in suffrage activism. By 1869, it was clear that the Fifteenth Amendment—the last of the Reconstruction Amendments to the U.S. Constitution (ratified in 1870)—would extend the franchise to African American males only. What is more, it did so in language that for the first time explicitly restricted the franchise to males. In response, women founded two national organizations, the radical-leaning National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the more conservative American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

And they would found one state organization whose accomplishments almost outshone them both: the New York State Woman Suffrage Association (NYSWSA).

“While the story of the national-level woman suffrage movement is one of repeated failure until its ultimate success in 1920, the story of the New York Woman Suffrage Association, founded in 1869, is one of minor, but repeated, successes," write historians Susan Goodier and Karen Pastorello. NYSWSA's success reflected balanced leadership and a structure ideally suited to the challenges it faced.

Origin of NYSWSA. After the text of the Fifteenth Amendment became clear, Fayetteville-based woman's rights activist Matilda Joslyn Gage called for a convention to establish a state suffrage organization. That convention took place on July 13–14, 1869, at Congress Hall in Saratoga Springs. Present were more than 100 delegates, including Susan B. Anthony; Rochester abolition and suffrage activist Amy Post; Lillie Devereux Blake; Auburn-based activist and donor Eliza Wright Osborne; and liberal cleric Samuel Joseph May. Gage was elected secretary of the organization.

NYSWSA was organized according to a grassroots structure proposed by Gage. Within the state association there would be a society for each county, and within each county there would be local societies for each city, town, and village. Any local suffrage group in the state could join NYSWSA by paying dues that began at $5 per year. This structure went far to explain why NYSWSA accomplished more than any other state-level suffrage group.

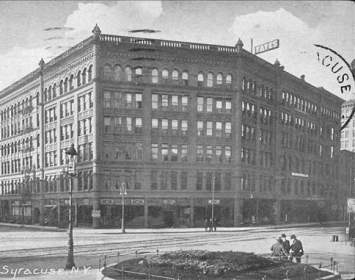

Conventions. A core element of NYSWSA strategy was to hold an annual convention in a different city each year. (The organization failed to hold a convention only once: in 1880, an exceptionally busy year that saw New York women win the right to vote in school board elections and serve on school boards.) County societies would compete to host the next convention and draw strength from the experience of staging it. In all, sixteen annual conventions were held in west-central New York State (the Freethought Trail's catchment area), including:

- Auburn in 1891 and 1904;

- Binghamton in 1913;

- Geneva in 1897 and 1907;

- Hornell in 1903;

- Ithaca in 1894 and 1911;

- Oswego in 1901;

- Rochester in 1890, 1896, 1905, and 1914;

- Syracuse in 1892 and 1906, and

- Utica in 1912.

From 1869 to 1874, conventions were held in high summer; after that, at Gage's suggestion, they were held in the autumn to take advantage of cooler weather.

Susan B. Anthony, president of NYSWSA from 1876 until 1877, keynoted at the annual conventions when her national obligations permitted. Anthony anchored so many of these events, both during and after her presidency, that one sometimes wonders how she found time for anything else. During those years Gage often represented the state association in Albany, spoke before legislative committees, worked to advance woman's rights bills, and took part in rallies and parades in New York City.

A Typical Victory. A noteworthy NYSWSA success story was the battle for women's right to vote in school-related elections. In 1877, the New York Legislature passed a bill allowing any woman qualified in the same ways required of a man to run for any office pertaining to school administration. Governor Lucius Robinson vetoed the bill. NYSWSA, Goodier and Pastorello write, responded by “coordinating the efforts to oppose him [Robinson]. Suffragists wrote letters and published circulars, raised money, and organized a statewide speaking tour.” Robinson was defeated by Alonzo Barton Cornell, a Republican whom the suffragists had endorsed. Had NYSWSA’s advocacy assured Cornell’s victory? No one was sure, but the Association seized an influential position in New York politics nonetheless. Meanwhile Lillie Devereux Blake, who had led the school-voting campaign, won election as NYSWSA president in 1879. She would serve for eleven years.

In 1881, the New York State Grange, a then-influential agricultural organization, adopted a resolution endorsing woman's suffrage after years of campaigning by NYSWA activists, particularly Eliza Gifford of Jamestown. Thereafter state suffrage leaders could honestly claim the large number of Grange members when boasting of how many New Yorkers backed suffrage.

“For the most part, during the last two decades of the twentieth century, suffrage activism remained concentrated in the central and western counties of the state,” Goodier and Pastorello wrote.

Political Equality Clubs. NYSWSA strategy moved to the next stage of its evolution when it encouraged activists in small towns and rural areas to organize "Political Equality Clubs" to pursue woman' suffrage but also a variety of other social issues. By 1890, such clubs had formed across much of central and western Central New York. Most affiliated with NYSWSA.

The Millers and the Mills. Also in 1890, at the twenty-second annual NYSWSA convention, held in Rochester, members voted to affiliate with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and even to adopt its constitution insofar as possible. Anthony (who also presided over this convention) had recently engineered a merger of NWSA and AWSA, producing the NAWSA. The New York association had resisted affiliating with NWSA, to which its leadership inclined, because of the latter’s focus on national-level suffrage work. After the merger, NAWSA carried forward AWSA’s focus on state-by-state organizing, and thus offered a better fit for NYSWSA.

Geneva-based activist Elizabeth Smith Miller—daughter of radical philanthropist Gerrit Smith—and her daughter Anne Fitzhugh Miller founded the Geneva Political Equality Club in 1897, when the NYSWSA annual convention was held in Geneva. In 1903, they formed a Political Equality Club for Ontario County, where Geneva was located, as well. Geneva's Political Equality Club was the largest in the state by 1907. Among its members were Geneva mayor Arthur Rose, Hobart College president Langdon C. Stewardson, and several local newspaper editors.

The early twentieth century saw frantic growth. In 1910, NYSWSA boasted 55,000 members from thirty-six counties and 155 affiliated suffrage clubs; just two years later, it had 450 branches across the state and an estimated 350,000 members.

Harriet May Mills of Syracuse, the daughter of abolitionist and freethinker C. D. B. Mills, was a longtime state organizer and NYSWSA vice president. She edited the monthly New York Suffrage Newsletter for Political Equality Clubs from 1899 to 1913), publicized the suffrage campaign at the New York State Fair in 1900 and 1903, and gave many well-received speeches on field work and the possible accomplishments of local suffrage groups.

During the teens of the twentieth century, much of the energy of the NYSWSA passed to the New York State Woman Suffrage Party, a more explicitly political organization.

NYSWSA took advantage of—and in later years, strongly influenced—a robust trend to expand the rights of women in New York. In 1860 (before NYSWSA was founded), legislation recognized property rights for women independent of their husbands and extended custody rights to their children. By 1880, women could vote in school board elections; women who owned property seized the right to vote and run for school commissioner in 1892 and the right to vote on measures about property assessments and tax increases in 1901. In 1913 came the right to vote on municipal tax propositions.

An Ingersoll Connection. Both of the daughters of nineteenth-century agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll resided in New York City and became involved with NYSWSA. Eva Ingersoll, the eldest, was an active feminist and suffragist. The younger sister, Maud Ingersoll Probasco, divided her energies among progressive politics, battling cruelty to animals, and suffrage work. Nonetheless, in 1913 Maud served as treasurer of NYSWSA.

Women Win the Vote in New York and Nationwide. In 1917, women won the vote in New York State. New York was the fourteenth state to enfranchise women but the largest and most populous state to have done so; the NYSWSA's responsive structure and high level of activism were much of the reason why.

Three more years would pass until the Nineteenth Amendment took effect on August 26, 1920, at last enfranchising women nationwide. Woman's enfranchisement came just as Jim Crow was taking hold in the South. At the same time, more subtle methods of suppressing the black vote spread across much of the North. These manifestations of racism meant that many African American women were unable to exercise their franchise until the mid-twentieth century or later, giving rise to a perception that suffrage had benefited primarily white women. But the fact remains that once race-based barriers to voting were removed, it was because of the Nineteenth Amendment—and the suffrage movement that had won it—that women of color faced no further obstacles to voting because of their sex.

And the New York State Woman Suffrage Association had played an outsized role in it all.

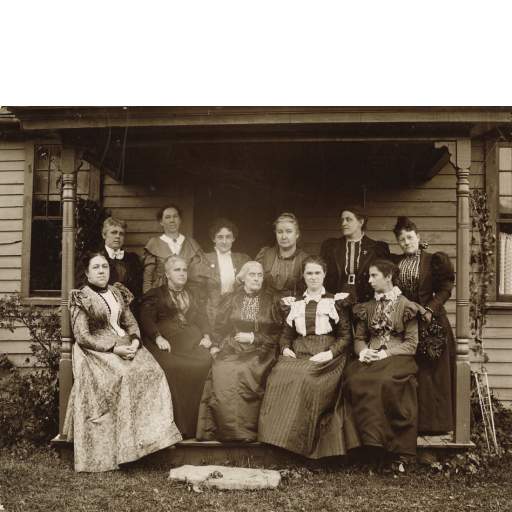

Susan B. Anthony with Suffrage Leaders

This 1896 photo shows Susan B. Anthony (first row, center) surrounded by New York suffrage leaders in 1896.

NYSWSA Convention Attendees

Group photograph from NYSWSA's annual convention in Buffalo (1902). Anna Howard Shaw, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, stands fourth from left in the front row. To her left is Ella Hawley Crossett (Warsaw) who had just been elected president of NYSWSA.

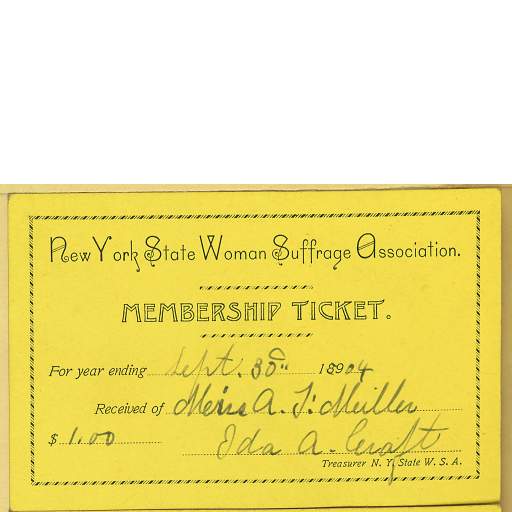

NYSWSA Membership Ticket

The 1904 NYSWSA membership ticket of Anne Fitzhugh Miller, daughter of activist Elizabeth Smith Miller.

Associated Causes

Associated Sites

Associated Historical Events

Twenty-Second NY State Suffrage Convention

December 16–18, 1890

Twenty-Third NY State Suffrage Convention

November 10–11, 1891

Twenty-Fourth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 14 –16, 1892

Twenty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 12–16, 1894

Twenty-Eighth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 17–19, 1896

Twenty-Ninth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 3–6, 1897

Thirty-Third NY State Suffrage Convention

October 29–November 1, 1901

Thirty-Fifth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 20–23, 1903

Thirty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 17–20, 1904

Thirty-Seventh NY State Suffrage Convention

October 24–27, 1905

Thirty-Eighth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 16–19, 1906

Thirty-Ninth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 15–18, 1907

Forty-Third NY State Suffrage Convention

October 31–November 3, 1911

Forty-Fourth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 15–18, 1912

Forty-Fifth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 14–17, 1913

Forty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 12–16, 1914