"Freethought" (one word) is the label most often embraced by atheists, agnostics, and secularists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. "Free thinking" (two words) could lead one to uncommon conclusions regarding any number of topics; "freethinking" (one word) came to mean the process by which one came to unorthodox conclusions about religion.

Freethinkers held that (either probably or certainly):

- God does not exist;

- Gods, scriptures, and religions are best understood as products of human action;

- Religion and government should be stringently separated; and

- Moral values should be sought in human experience, not in holy books.

Of course, this is essentially identical to the worldview held by twentieth and twenty-first–century secular humanists.

Writing in 1943, the prominent historian Allan Nevins described "the vigorous contest between freethinkers and religionists which was so important a part of the cultural history of the nineteenth century," and judged that "the battle which the freethinkers waged was in great part a wholesome and beneficial effort."

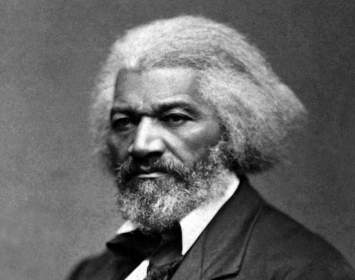

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when west-central New York State played a social role much like the one southern California would play later in the twentieth century, freethinkers tended to be involved in a wide variety of radical social reform efforts. Most of the prominent American anarchists were atheists, for example. Critics of religion were prominent in the abolition movement; they were especially visible in opposing the idea that slavery was ordained by God. Freethinkers were over-represented among so-called sex radicals, who championed everything from the abolition of marriage to birth control, then a controversial notion. They were also prominent among proponents of woman’s rights and woman suffrage; indeed, two of the three leaders of the nineteenth-century suffrage movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage, were explicit freethinkers. (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman or woman's, when referring to women as a class; later practice was to use the plural, women or women's.)

Freethinkers of this period had other associations that many today would find surprising. There was considerable overlap between the freethought and Spiritualist movements. That seems strange today, when atheists and secular humanists are often associated with groups skeptical of paranormal claims. But it should be recalled that in its earliest years, Spiritualism was imagined by some to be a "scientific" exploration of the afterlife. Moreover, what Spiritualism asserted about the afterlife contradicted the doctrines taught by traditional churches, and was welcomed by some freethinkers for that reason alone. In addition, during the late nineteenth century the conclusive evidence of misdirection and fraud among spirit mediums now available had not yet come to light.

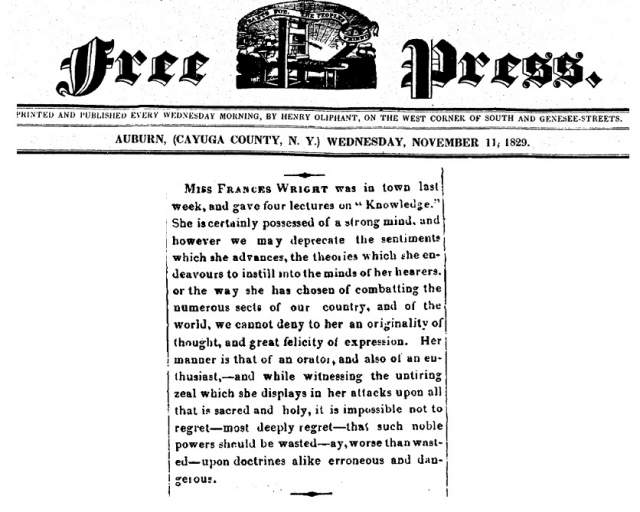

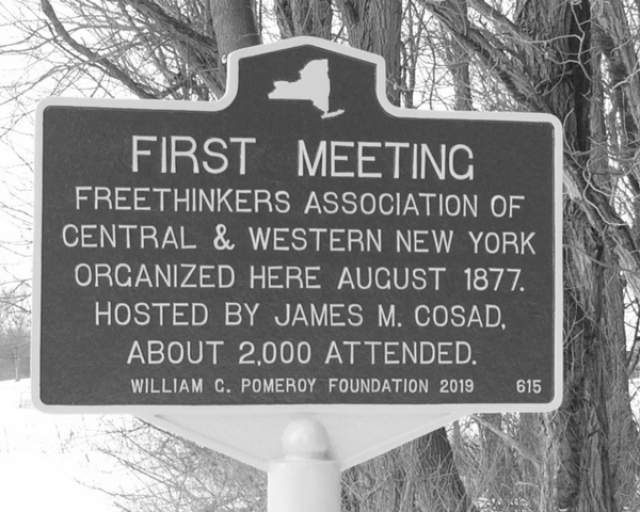

Of course, there was no shortage of freethinkers whose activism was principally concerned with challenging religious dogmas. An earlier generation brought forth Frances "Fanny" Wright, a freethinker, anti-slavery activist, and sex radical who was also the first woman to lecture before mixed-sex U. S. audiences during the 1820s. Important later in the nineteenth century were orator Robert Green Ingersoll, journalist Obadiah Dogberry, organizer C. D. B. Mills, and educator Andrew Dickson White. Also noteworthy was the New York Freethinkers Association, an organization of national significance that held its initial convention in Huron in 1877. This was followed by two important conventions in Watkins, now Watkins Glen. The first of the Watkins conventions, held in 1878, was the site of events that would lead indirectly to the standard for obscenity upheld by U.S. courts until 1959. A quirky early twentieth-century group, the American Association for the Advancement of Atheism, attracted press attention wildly out of proportion to its negligible size and influence; an under-resourced attempt to organize atheist groups at schools and colleges across the country led to a brief scandal at the University of Rochester that won national media attention, and, strangely, inspired Hollywood impresario Cecil B. DeMille's final silent film.

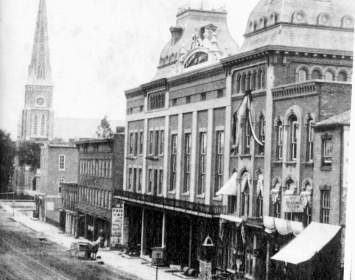

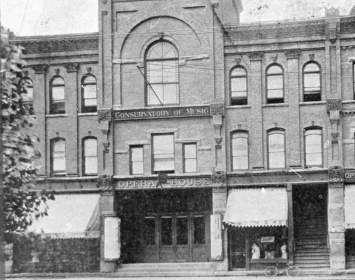

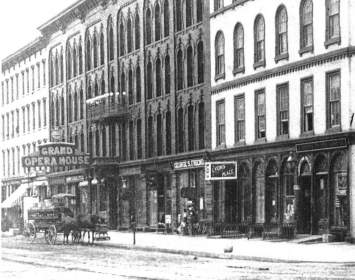

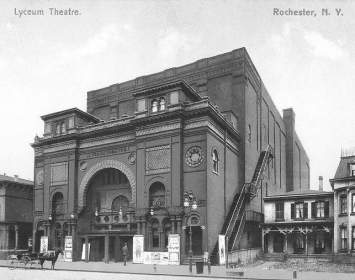

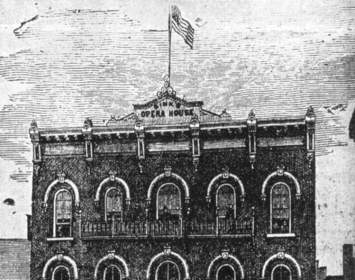

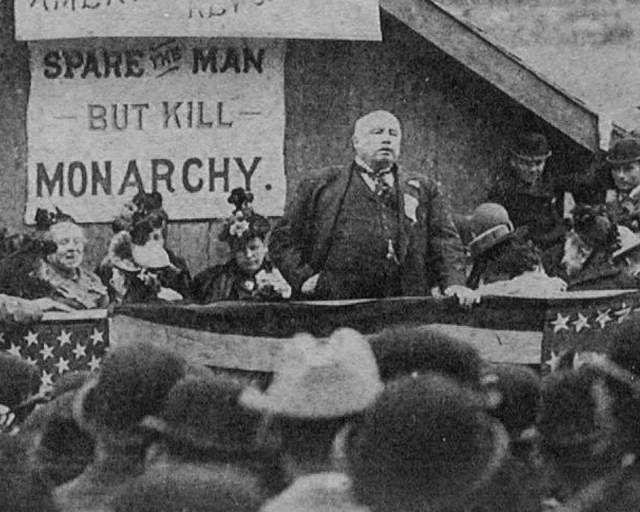

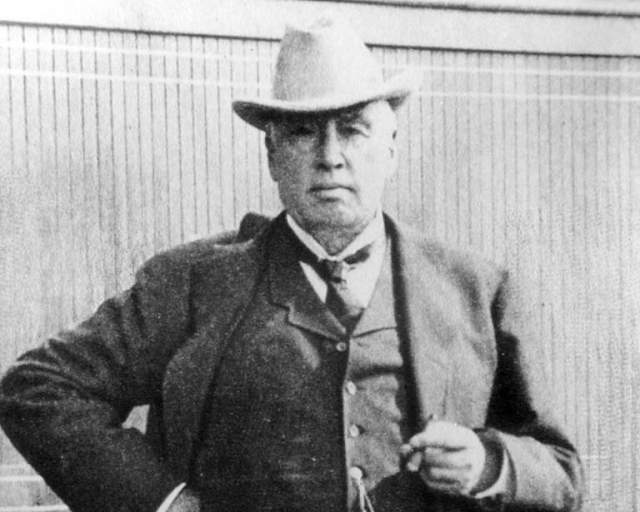

As for Ingersoll, he was seen and heard by more Americans than any other person prior to the advent of motion pictures and radio. This was because he traveled the country on frequent speaking tours throughout an almost thirty-year career. Ingersoll delivered some thirty-three lectures at seventeen theaters, opera-houses, and fairgrounds between Rochester and Utica, all of which are now sites on the Freethought Trail. Of those seventeen venues, only one, the Breese Opera House in Norwich, still stands.

The story of American freethought is rich in the unexpected, and it's all on the Freethought Trail.

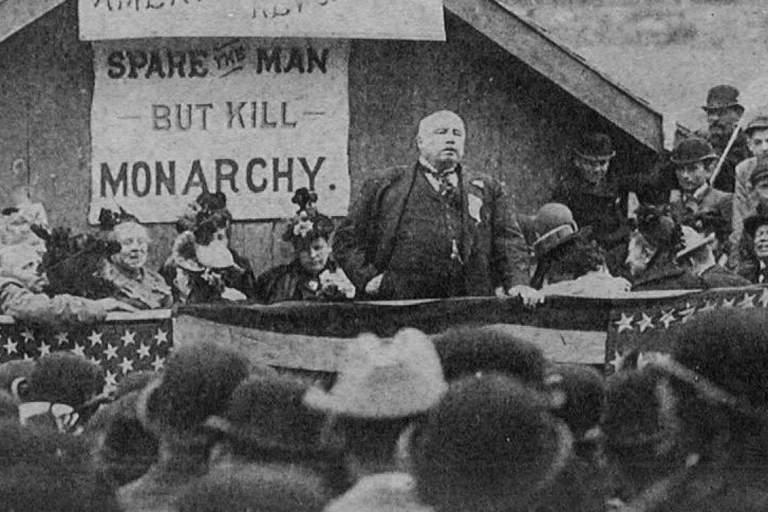

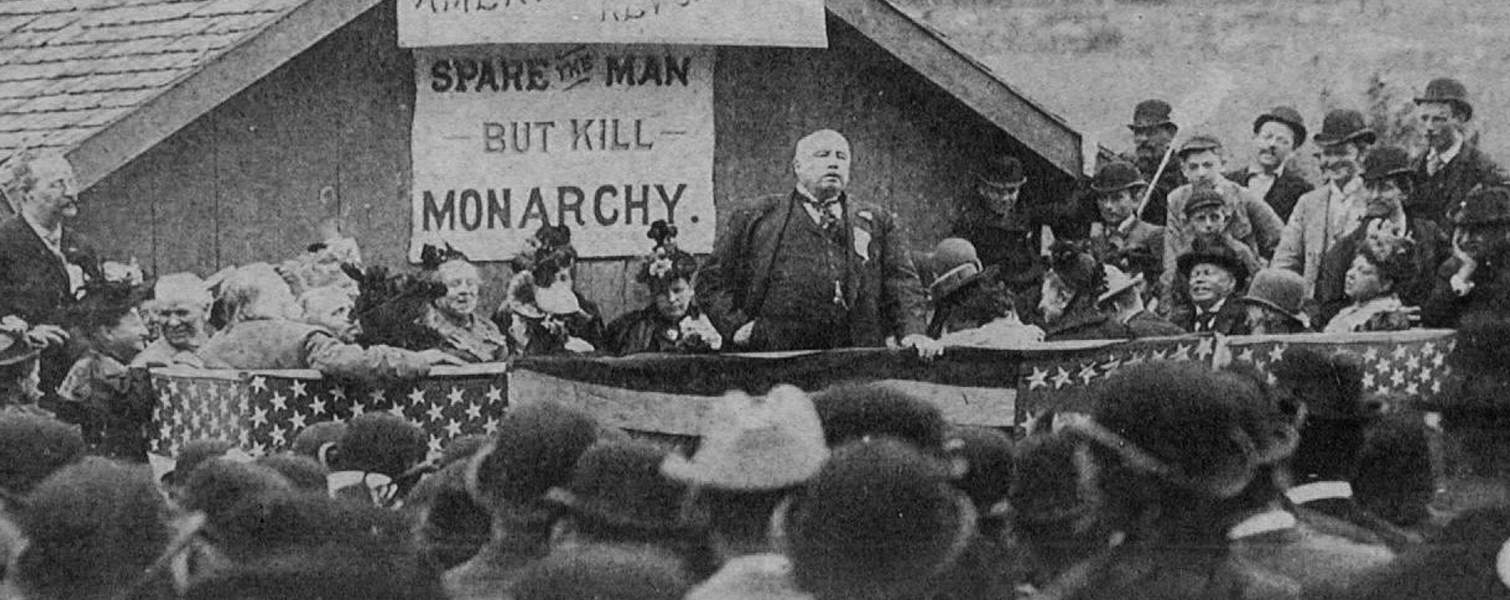

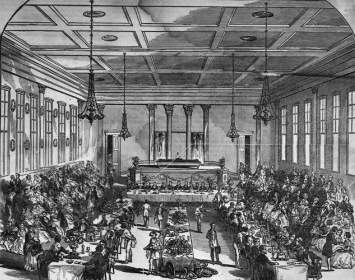

Only known photo of Robert Green Ingersoll addressing an audience, May 30, 1884.

The only known photo of Robert Green Ingersoll addressing an audience at a Thomas Paine memorial gathering at New Rochelle, New York, on May 30, 1884. Photograph commissioned by the freethought newspaper The Truth Seeker.

Estate of Gordon Stein.

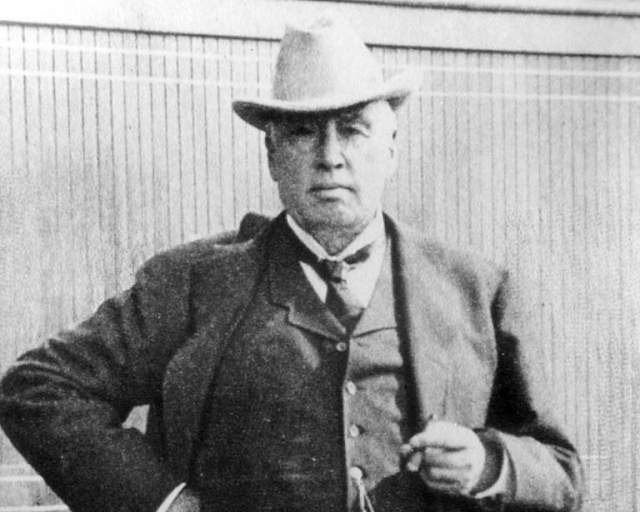

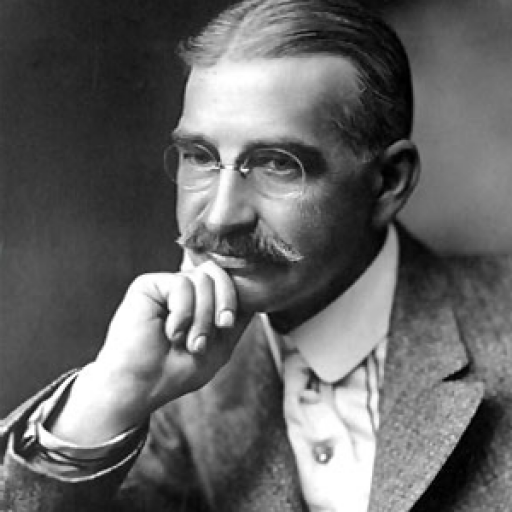

L. Frank Baum

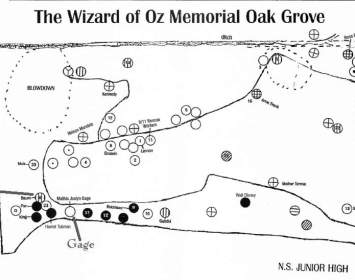

L. Frank Baum (1856–1919) a freethinker? Oh yes. Strongly influenced by his freethinker/ suffragist mother-in-law Matilda Joslyn Gage, the Chittenango-born Baum filled his Oz books and other children's fantasies with strong female characters, societies that solve their problems without religion, and godlike figures that merit vigorous skepticism (not to mention a relentless look behind the curtain).

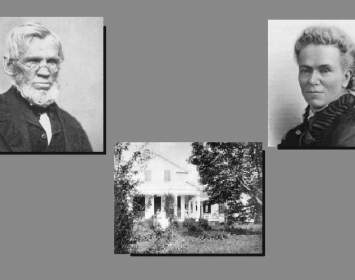

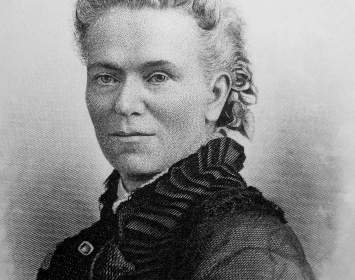

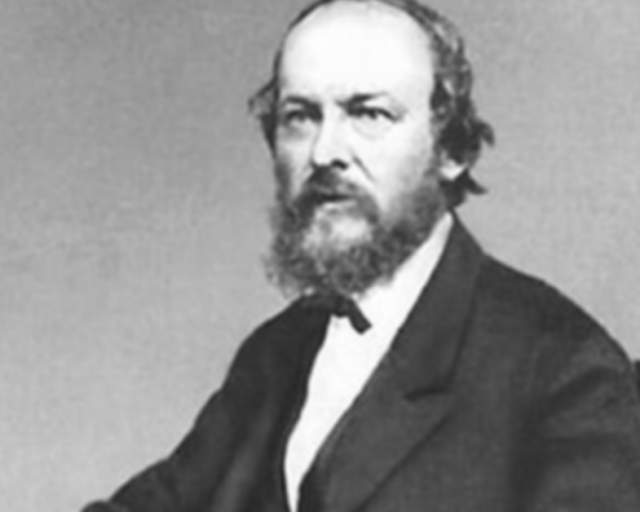

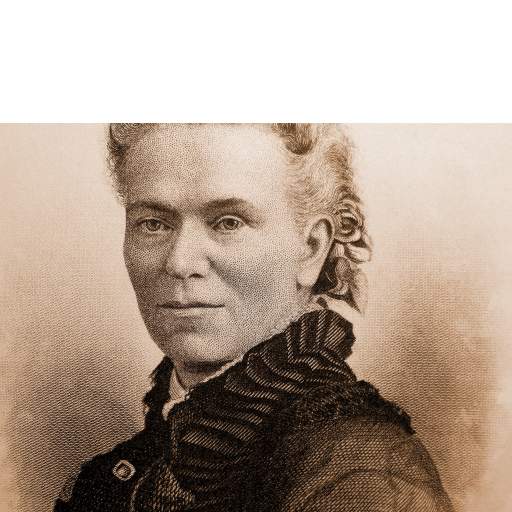

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–1898) was a lifelong activist: first for abolition, then for woman's rights, and finally for freethought. After 1878 her outspoken criticism of Christianity as woman's oppressor would gradually see her driven from the suffrage movement.

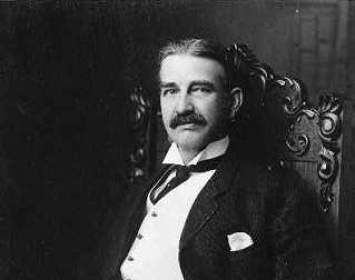

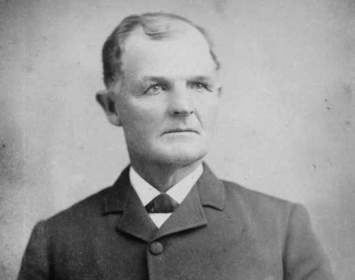

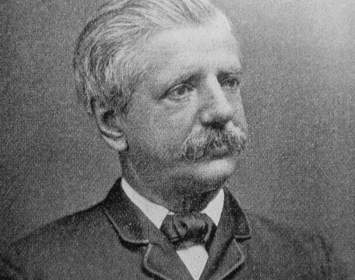

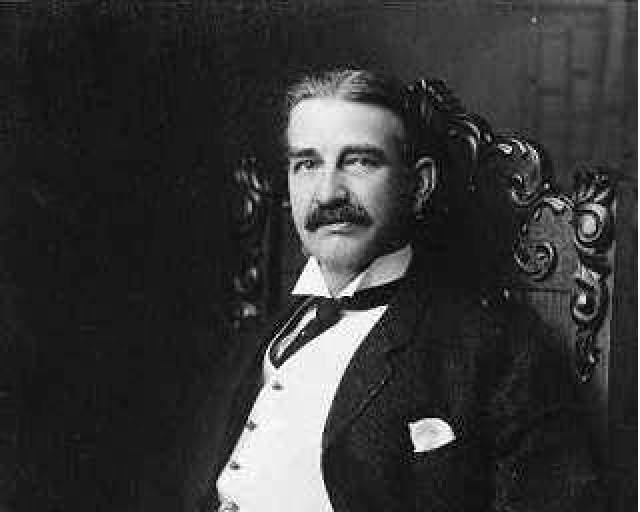

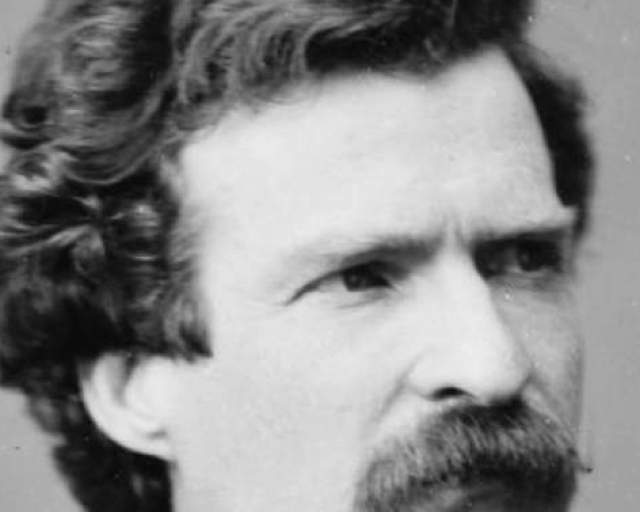

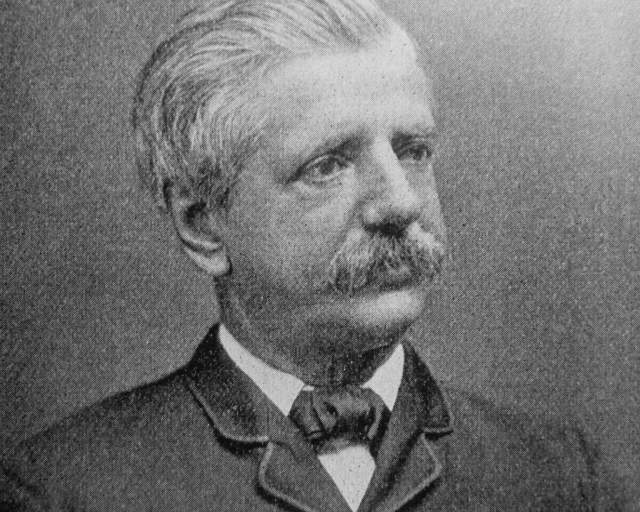

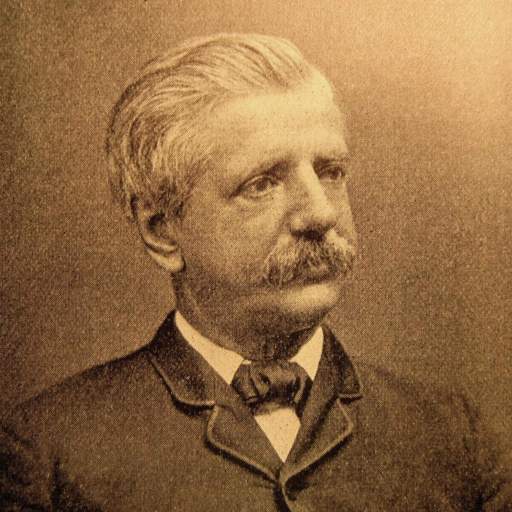

Robert Green Ingersoll

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) was a true polymath: attorney, patron of the arts, and an incomparable freethought lecturer. In almost three decades of regular touring, he would be seen and heard by more Americans than any other person prior to the advent of motion pictures and radio. His birthplace in Dresden is North America's only freethought museum.

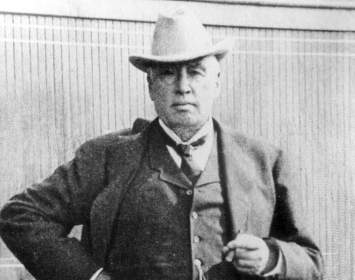

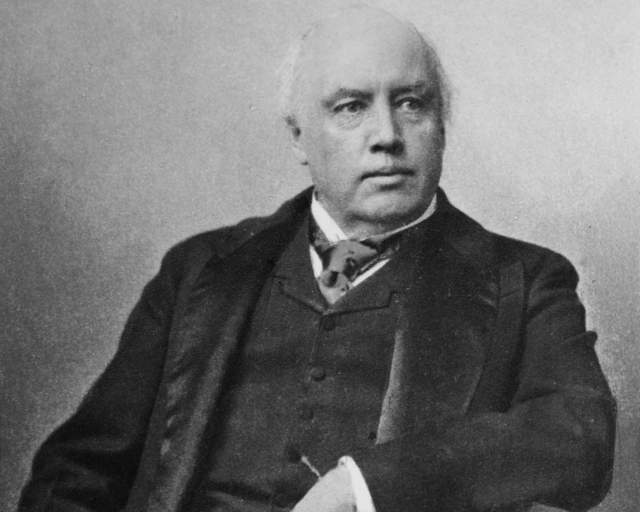

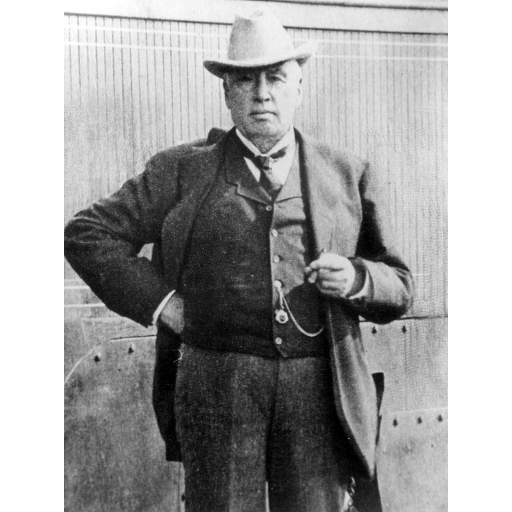

Charles B. Reynolds

Charles B. Reynolds (1832–1896) renounced Seventh-day Adventist ministry for freethought circa 1880. In 1882 he began freethought "revival preaching" on stage and in his own freethought "revival tent." In 1886, a mob in Boonton, New Jersey, destroyed his tent. Three months later, nearby Morristown put him on trial for blasphemy. His defense attorney would be none other than Robert Green Ingersoll.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) helped organize the 1848 Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls that launched the suffrage movement. For decades she led that movement alongside Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage. Long a freethinker, Stanton only made her heterodox views clear beginning in 1895. By 1898 she had been largely ejected from the suffrage movement, and was able to publish only in freethought periodicals.

Associated Sites

Those Involved

Associated Historical Events

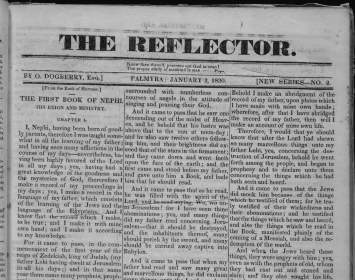

Book of Mormon First Criticized by Obadiah Dogberry

January 2–22, 1830

Birth of Robert Green Ingersoll

August 11, 1833

Birth of L. Frank Baum

May 15, 1856

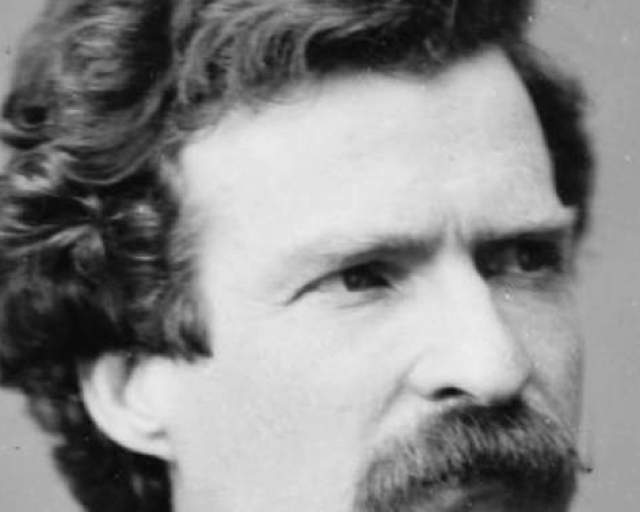

Mark Twain Gives "The American Vandal" Lecture in Elmira

November 23, 1868

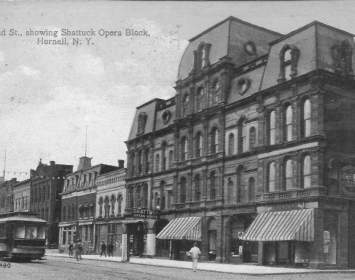

Mark Twain Gives Unknown Lecture in Hornellsville

January 20, 1870

Mark Twain Gives "Artemus Ward" Lecture in Auburn

December 5, 1871

Mark Twain Gives "Artemus Ward" Lecture in Syracuse

December 6, 1871

First National Liberal League Convention

October 26, 1877

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Ghosts" Lecture in Utica

February 20, 1878

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Individuality" Lecture in Rochester

February 21, 1878

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Ghosts" Lecture in Syracuse

February 22, 1878

Second New York Freethinkers' Association Convention

August 22–25, 1878

Second National Liberal League Convention

October 26–27, 1878

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Robert Burns" Lecture in Utica

October 30, 1878

Fourth New York Freethinkers Association Convention

September 2–6, 1880

Fifth New York Freethinkers Association Convention

August 31–September 4, 1881

Sixth New York Freethinkers' Association Convention

August 23–27, 1882

Memorial Meeting Honoring D. M. Bennett

December 1882

Seventh New York Freethinkers Association Convention

August 29, 1883

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Orthodoxy" Lecture in Utica

January 19, 1885

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Orthodoxy" Lecture in Auburn

January 21, 1885

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Orthodoxy" Lecture in Oswego

January 23, 1885

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Which Way?" Lecture in Rochester

January 26, 1885

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Orthodoxy" Lecture in Norwich

February 26, 1885

Lectures by Rev. and Mrs. C. B. Reynolds in Hornellsville

March 20–21, 1886

C. B. Reynolds Gives Freethought Lecture

June 25, 1886

Early Life of L. Frank Baum

1861–1888

Ingersoll Visits His Birthplace

September 24, 1889

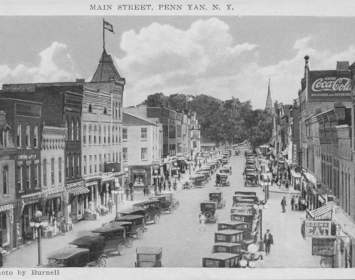

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives Lecture at Yates County Fair

September 25, 1889

Only Return to His Birth County by Robert Green Ingersoll

September 24–25, 1889

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Lincoln" Lecture in Syracuse

April 27, 1894

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives "Foundations of Faith" Lecture in Rochester

February 23, 1896

Robert Green Ingersoll Gives Unknown Lecture in Rochester

January 5, 1898

Mid to Late Life of Mark Twain

1867–1910

Scandal of the Society of Damned Souls

1926–1927

Grave of Mary Livingston Ingersoll Located

December 23, 2015