"[S}uffrage ... is so often described in a way that makes it seem kind of dowdy and dour — whereas in fact it is exciting and radical. Women staged one of the longest social reform movements in the history of the United States. This is not a boring history of nagging spinsters; it is a badass history of revolution staged by political geniuses. I think that because they were women, people have hesitated to credit them as such."

Kate Clarke Lemay, historian and curator at the National Portrait Gallery.

Jessica Bennett and Veronica Chambers, "This Is Not a Boring

History of Nagging Spinsters." New York Times, July 10, 2020.

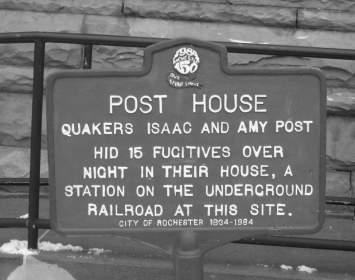

The woman's rights/suffrage movement descended from the abolition movement. Many early suffragists formed the habit of activism and learned core tactics in anti-slavery work or by taking part in the Underground Railroad. It may come as more of a surprise that deep overlaps exist between nineteenth-century woman’s rights and suffrage activism—indeed, nineteenth-century feminism generally—and the freethought movement. But truly, that should surprise no one. After all, the traditional Christian churches of that time were ferocious defenders of two ancient certainties: (1) women were inferior because God had made them that way, and (2) male domination over women was simply part of God’s plan. And did we mention that God is male?

Given all of this, it makes sense that the three ranking leaders of the nineteenth-century woman’s rights and suffrage movements were an outspoken freethinker (Elizabeth Cady Stanton) ... an outrageously outspoken freethinker (Matilda Joslyn Gage) ... and Susan B. Anthony. (And yes, each had also begun her radical-reform career in abolition work.)

Anthony was the "traditionalist" of this group, but even she was a radical religious liberal (first a Quaker, later a Unitarian). Even so, at the height of her power over the suffrage movement, Anthony would make overtures to religious conservative groups, believing such alliances necessary to win women the vote.

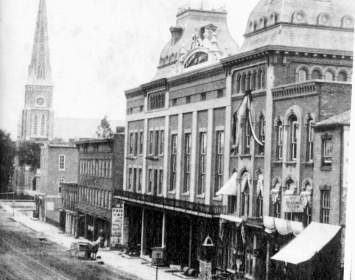

New York's Centrality to the Movement. While the pre-Civil War abolition movement had been principally centered in New England, with west-central New York its the next-most active region, when the suffrage movement arose (starting in 1848) that situation was reversed. West-central New York unquestionably led the movement, originally owing much to the influence of Anthony, Stanton, and Gage. As suffrage and woman's-rights campaigning blossomed after the Civil War, New York boasted the nation's largest state-level organization, the New York State Woman Suffrage Association (NYSWSA). (Nineteenth-century practice was to use the singular, woman's; later practice was to use the plural, women's.) New York also enjoyed the best-developed network of county-level and local affiliate organizations found in any state, and the movement's best-organized and largest-scale programs of protest and activism. From 1860 to 1920, when the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution made woman suffrage the law of the land, NYSWSA would hold large, well-organized annual conferences all across the state. Between 1890 and 1914, no fewer than sixteen of these conventions took place in west-central New York.

Suffrage organizers often took advantage of a profusion of socially liberal churches that had split from their parent congregations before the Civil War over issues of slavery and abolition. Conspicuous among these was the Wesleyan Methodist Church, which had withdrawn from its parent Methodist Episcopal Church in 1841 in order to advocate the immediate abolition of slavery. Wesleyan congregations tended to be strongly socially liberal; some of their ministers supported agendas so radical that they were only marginally distinguishable from freethought. Many Wesleyan churches had served as stations on the Underground Railroad and made their facilities available for abolition meetings; after the Civil War Wesleyan and other liberal churches often hosted woman suffrage events whose programs were not conspicuously religious. Indeed, the 1848 woman's rights convention in Seneca Falls that launched the nineteenth-century suffrage movement took place in a Wesleyan chapel.

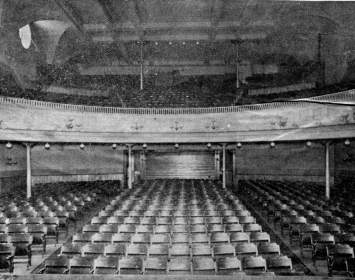

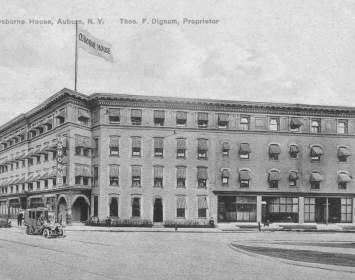

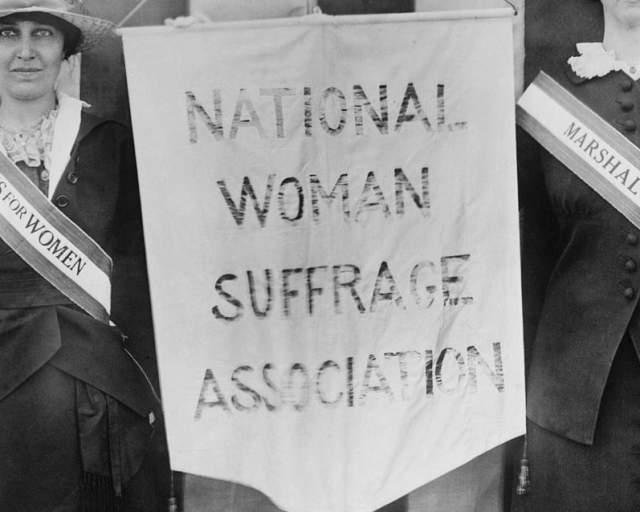

The Campaign and Its Aftermath. The suffrage movement mounted one of the most-massive and longest-duration reform efforts in American history. Suffrage campaigners paraded in white and channeled their activism into a complex web of national, state, and local organizations. New York was a principal center of this activism. Among other things, the New York State Woman Suffrage Association held annual conventions that rotated among the state's cities. Such conventions usually occupied the premier venues in the city where they took place and attracted large crowds of suffrage activists, almost invariably featuring Susan B. Anthony as keynote speaker until her death in 1906.

When women won the vote in 1920, the National American Woman Suffrage Association was the foremost pro-suffrage organization. It became the League of Women Voters, still active today.

Yet suffrage was not to be achieved without controversy.

Post-Civil War Years: Breach and Reunification. After 1865, the movement split due to strategic disagreements and regional factionalism. The dominant central New York–based wing of the movement, led by Stanton, Anthony, and Gage, charted a radical course: demanding federal action for immediate enfranchisement of women, criticizing the Fifteenth Amendment because it did not extend the vote to women, and pursuing reforms including an eight-hour work day, equal pay, and greater rights in marriage and divorce. In other words, the New York wing pursued a broad range of foundational reforms, all of benefit to women alone. The other, smaller wing, based in New England and led by Lucy Stone, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and others, was willing to pursue suffrage state by state. The New England wing sought suffrage alone, for women and for African Americans, and resisted involvement in reform efforts additional to suffrage.

In 1869, the two wings separated. The New York wing formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) while the New England wing formed the more moderate American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The NWSA permitted men to join as members but not to become officers, while the AWSA allowed men in leadership roles. As historians Susan Goodier and Karen Pastorello expressed it in their book Women Will Vote (Ithaca, N.Y.: Three Hills Press, 2017), "the split in ideology between those who supported black men’s rights and those who sought universal rights fractured the women’s movement for more than two decades. And, with the greater national focus on voting rights, women’s rights activists shifted their focus to the singular demand for woman suffrage."

Only in 1890 was the breach healed, if clumsily, with the creation of a unity organization: the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). NAWSA took its moderate agenda from AWSA almost unchanged, as though New England were finally asserting dominion over New York after all. NAWSA abandoned radical social objectives such as legalizing divorce and fighting abuse of working-class women. One newspaper of the day called it "toothless."

Stanton drifted away from the movement. Far from embracing AWSA's pursuit of woman suffrage and nothing else, she felt that "suffrage is but the vestibule of woman’s emancipation.” Already marginalized because of her outspoken views on religion, Gage made her final break with the suffrage movement. She turned instead to freethought activism.

Suffrage: Only for White Women? The woman suffrage movement was often in tension with the movement for racial equality. Before and especially after the Civil War, there was acrimonious debate among reformers whether African Americans or women were more deserving of the vote. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and some other suffrage leaders were dismayed when the Fourteenth Amendment (adopted in 1868) guaranteed citizenship, and with it the vote, to all males regardless of race. This was the first time the Constitution explicitly characterized the franchise as belonging only to men. Stanton attacked the amendment as "manhood suffrage" and "establishing an aristocracy of men."

Woman's enfranchisement came just as Jim Crow was taking form in the South. At the same time, more subtle methods of suppressing the black vote spread across much of the North. These manifestations of racism meant that many African American women were unable to exercise their franchise until the mid-twentieth century or later, giving rise to a perception that suffrage had benefited primarily white women. But the fact remains that once race-based barriers to voting were removed, it was because of the Nineteenth Amendment—and the suffrage movement which had won it—that women of color generally faced no further obstacles to voting because of their sex.

An Experiment in Applied Radicalism. All told, suffrage was a profoundly radical movement. Inspired by the success of America's campaign to abolish slavery, it sought to upend one of Western society’s most deeply rooted traditions: the systematic disenfranchisement of half of humanity. Small wonder freethinkers were numerous within its ranks.

These nineteenth-century movements helped to shape the twentieth century and beyond, most of all with the extension of the franchise to women in 1920.

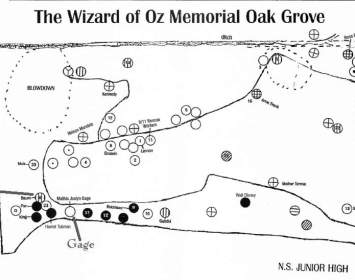

There were other influences, too, including the hugely popular children’s books of L. Frank Baum, who married the youngest daughter of Matilda Joslyn Gage and spent years absorbing Gage’s freethinking and feminist ideas. In Baum’s land of Oz women are men’s equals; religion is all but absent; and free individuals of either sex work out their differences with little involvement by the state.

This excitement all began in west-central New York State ... on today’s Freethought Trail.

Second generation suffragists parading in 1912

Second-generation suffragists parading in 1912.

Frances "Fanny" Wright

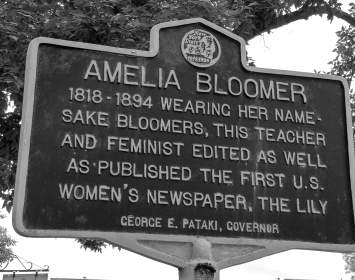

Frances "Fanny" Wright (1795–1852) was a prominent early feminist and sex radical, as well as an abolitionist and a freethinker. She was one of the first women to address audiences of mixed sex across the United States, including in west-central New York State, and led a life of sexual liberation by the standards of her time.

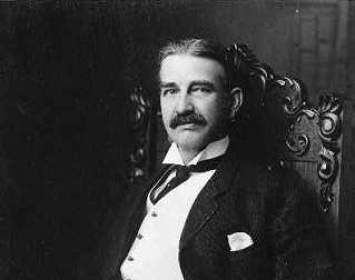

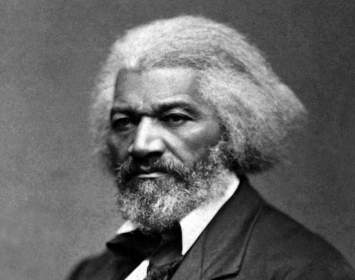

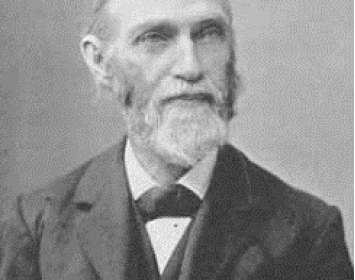

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) began her career in abolition work before emerging as one of the three major leaders of the woman suffrage movement alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage. When suffrage was finally achieved in 1920 through the Nineteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution, it was popularly called "the Susan B. Anthony Amendment."

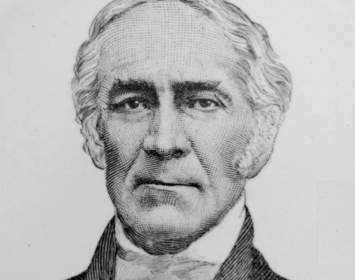

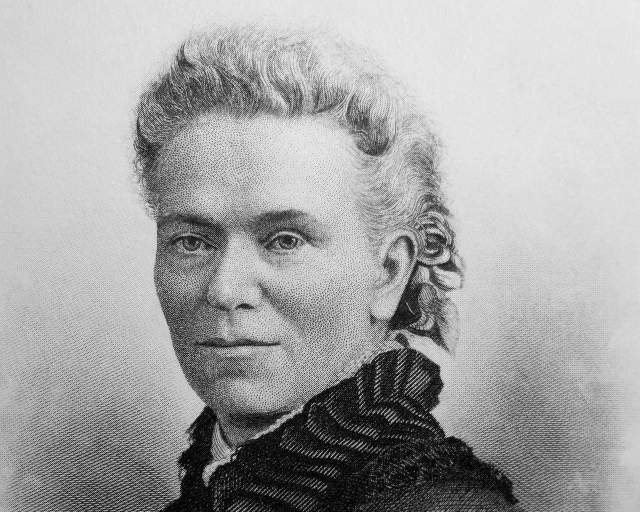

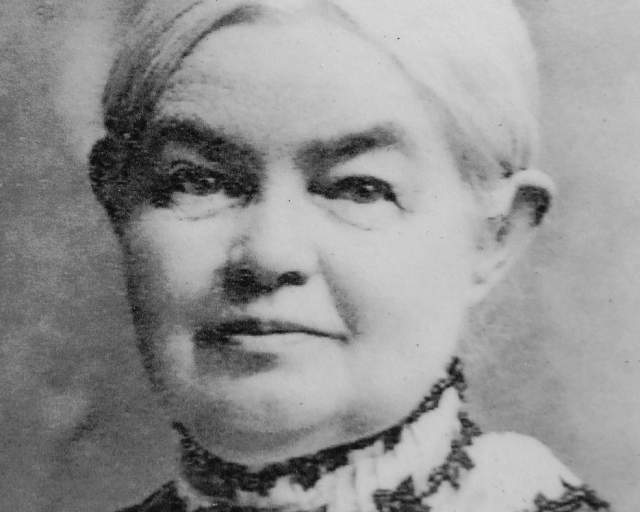

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) helped organize the 1848 Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls that launched the suffrage movement. For decades she led that movement alongside Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage. Long a freethinker, Stanton only made her heterodox views clear beginning in 1895, when she published the first volume of her Woman's Bible. By 1898 she had been largely ejected from the suffrage movement, and was able to publish only in freethought periodicals.

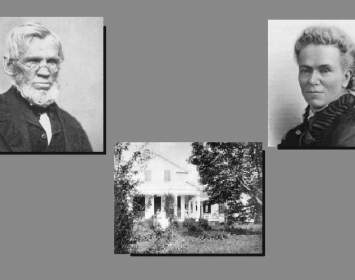

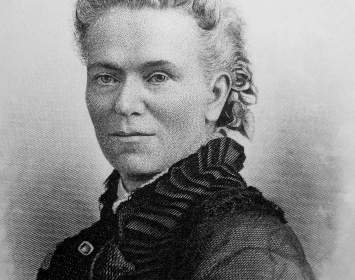

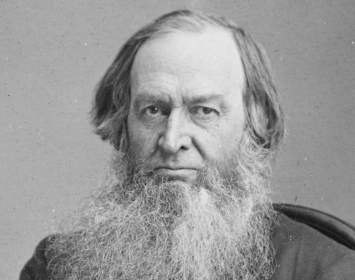

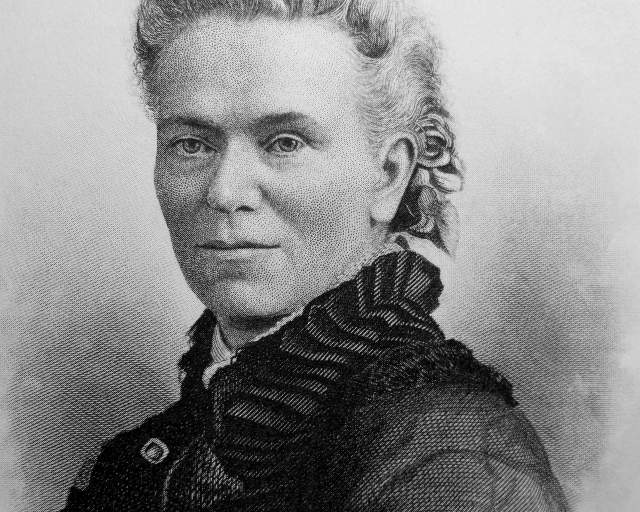

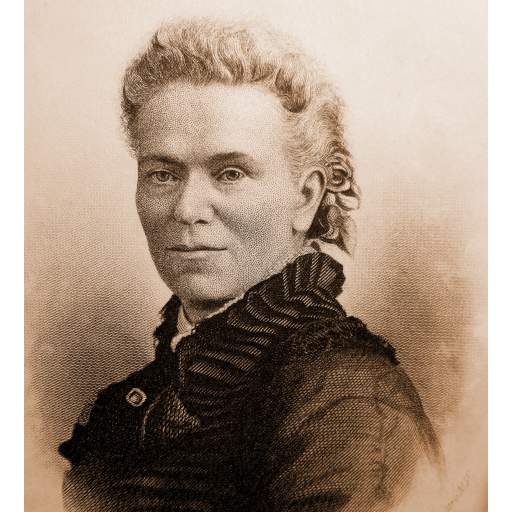

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–1898) grew up in an abolitionist household. She soon embraced the woman suffrage movement, emerging alongside Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the "Triumvirate" who led the movement in its early decades. After 1878 Gage's outspoken criticism of Christianity as woman's oppressor would gradually see her driven from the suffrage movement. She ended her career as a freethought activist.

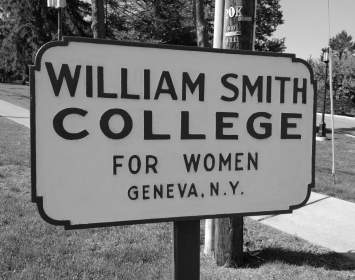

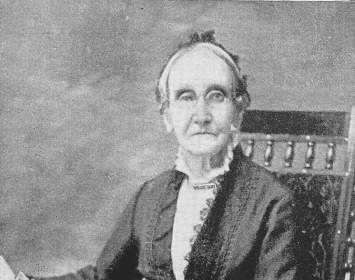

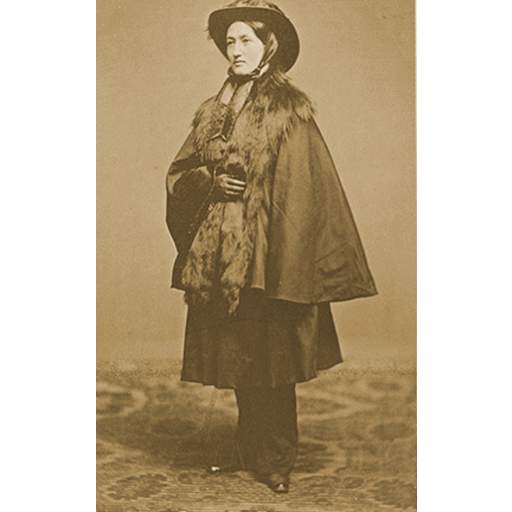

Elizabeth Smith Miller

Elizabeth Smith Miller (1822–1911), daughter of philanthropist Gerrit Smith, campaigned for woman's rights / suffrage and financially supported the movement. She became best known as a dress reformer, inventing the so-called "Bloomer" costume of a practical knee-length skirt over pantaloons (shown). In later life she persuaded Geneva millionaire William Smith to fund a revolutionary college for women that still operates today.

Associated Sites

Those Involved

Associated Historical Events

Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls

July 19–20, 1848

Follow-On Woman's Rights Convention

August 2, 1848

Third National Woman’s Rights Convention

September 8–10, 1852

Woman's Rights Convention in Penn Yan

January 10, 1855

Mary Edwards Walker Addresses Major-Party Political Convention

October 24, 1864

Susan B. Anthony Lectures at Library Hall

March 26, 1869

The Arrest of Susan B. Anthony

November 18, 1872

The Trial of Susan B. Anthony

June 18–20, 1873

1878 Woman's Rights Convention

July 19, 1878

Matilda Joslyn Gage Speaks on Woman's Rights at Sage College

February 26, 1881

Twenty-Second NY State Suffrage Convention

December 16–18, 1890

Twenty-Third NY State Suffrage Convention

November 10–11, 1891

Twenty-Fourth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 14 –16, 1892

Local Suffrage Meeting to Amend NYS Constitution

March 27–29, 1894

Susan B. Anthony Lectures in Utica

April 19, 1894

Susan B. Anthony Dines/Speaks at Sage College

November 14, 1894

Twenty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 12–16, 1894

Twenty-Eighth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 17–19, 1896

Twenty-Ninth NY State Suffrage Convention

November 3–6, 1897

Death of Matilda Joslyn Gage

March 18, 1898

Thirty-Third NY State Suffrage Convention

October 29–November 1, 1901

Thirty-Fifth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 20–23, 1903

Thirty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 17–20, 1904

Thirty-Seventh NY State Suffrage Convention

October 24–27, 1905

Thirty-Eighth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 16–19, 1906

Death of Susan B. Anthony

March 13, 1906

Thirty-Ninth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 15–18, 1907

Founding of William Smith College

1908–1911

Forty-Third NY State Suffrage Convention

October 31–November 3, 1911

Forty-Fourth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 15–18, 1912

Forty-Fifth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 14–17, 1913

Forty-Sixth NY State Suffrage Convention

October 12–16, 1914